David Y. Yang.

Niles Singer/Harvard Staff Photographer

When global trade is about more than money

Economist’s new tool looks at how China is more effective than U.S. in exerting political power through import, export controls

International trade can yield far more than imports and exports. According to David Y. Yang, Yvonne P. L. Lui Professor of Economics, trade can be used to wield political power.

Yang watched as China imposed trade restrictions on competitor Taiwan following a 2022 visit to the island by U.S. Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi. A decade earlier, the arrest of a Chinese fishing boat captain in contested waters culminated with Beijing blocking exports to Japan of certain rare earth minerals, critical components for wind turbines and electric vehicles.

“Another example is China banning the import of Norwegian salmon for nearly a decade as punishment for awarding a Nobel Prize to the dissident Liu Xiaobo,” said Yang, a political economist with expertise in the East Asian superpower.

His latest working paper, co-authored with Princeton’s Ernest Liu, presents a framework for measuring how much geopolitical muscle a country can flex by threatening trade disruptions. Today, the economists find, China exerts outsized influence over trading partners while the United States has less power than expected relative to the size of its economy

“With the arrival of new data sources and empirical tools, this is something we can now study very rigorously,” Yang emphasized. “Conducting these objective, data-driven analyses feels all the more urgent in today’s global geopolitical climate.”

Their model specifically tests a set of predictions made by mid-20th-century Harvard professor Albert O. Hirschman, a German-born Jew who fled Europe during World War II. His book “National Power and the Structure of Foreign Trade” (1945) offered a theoretical account of how countries might use trade to assert geopolitical dominance.

“Hirschman viewed the issue through a positive lens,” Yang noted. “Rather than bombing each other, countries could just fight economic wars to achieve the same goals.”

Hirschman saw that trade asymmetries could be exploited. But deficits and surpluses weren’t the only relevant variables. Also important was how crucial and easily replaced the goods in question were. Halting the flow of crude oil tends to pack a far bigger punch than withholding textile exports.

“If one country becomes overly reliant on another, it might be economically efficient,” Yang explained. “But it can leave the first country vulnerable by exposing it to unfavorable power dynamics.”

Hirschman’s ideas seemed less relevant in the post-war years, with the widespread desire for increased free trade. But the book feels fresh again today, said Yang, who recently assigned it in an undergraduate economics course.

“I asked students to read the first few chapters and guess when it was written,” he recalled. “Many guessed it was last year.”

Yang and Liu set about formalizing Hirschman’s vision about three years ago, long before the current suite of aggressive U.S. tariffs. “A lot of the anecdotal examples that motivated our work came from China,” Yang said.

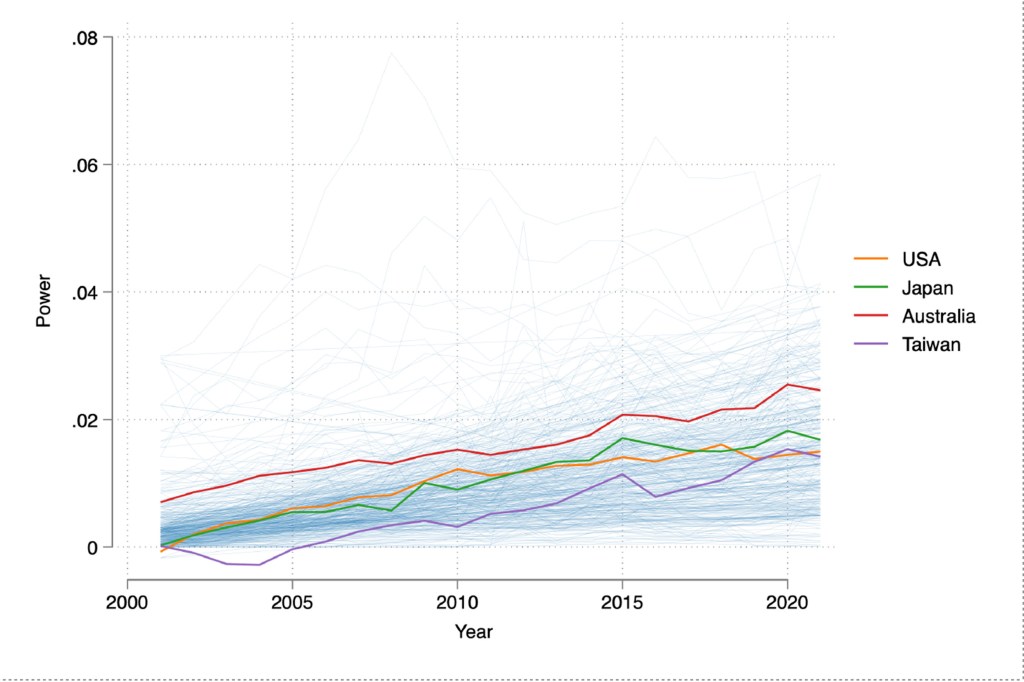

Indeed, their model shows China’s trade power rising over the past two decades as it turned key industries into political instruments. Chemical products, medical instruments, and electrical equipment emerged as especially potent. The country’s trade power proved larger than expected given the size of its GDP, second to the world’s largest economy by many trillions of dollars.

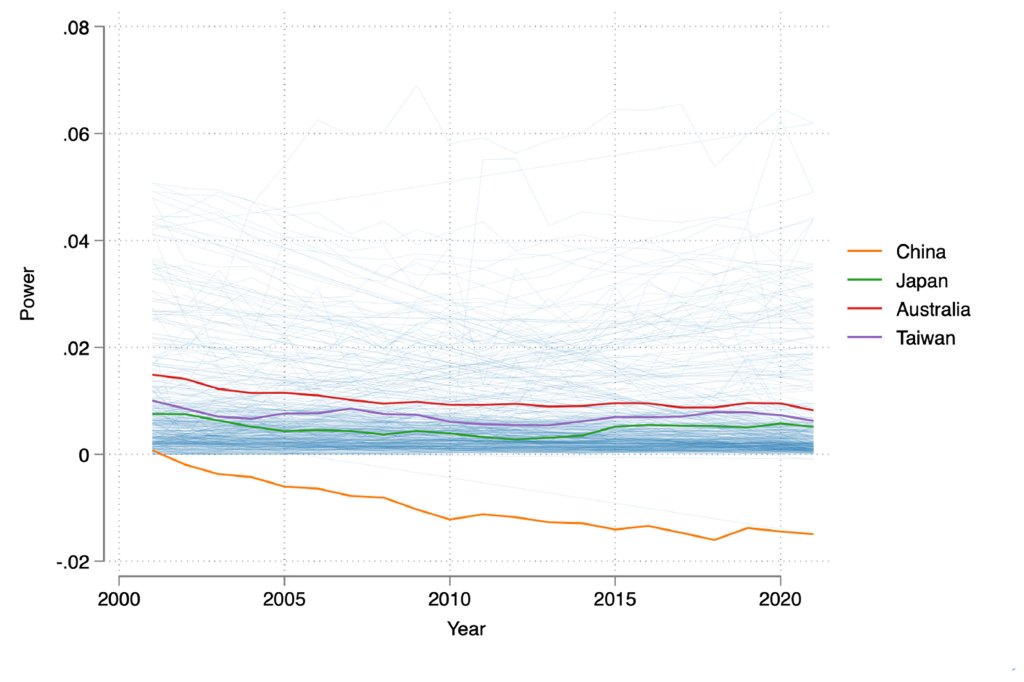

U.S. trading power over China declines

This figure plots the directed power (in all sectors) between the U.S. and a country for each year.

Credit: Ernest Liu and David Y. Yang

“In the early 2000s, the U.S. was able to exert more absolute power over China through trade disruptions,” said Yang, noting that findings on the U.S. were relatively stable over the 20-year period they studied.

“But things have quickly flipped,” he continued. “China now has more trade power over the U.S. and, at the moment, can exert positive power over any other entity in the world.”

China’s trading power on the rise

This figure plots the directed power (in all sectors) between China and a country for each year.

Credit: Ernest Liu and David Y. Yang

Yang and Liu also tested a pair of predictions concerning the consequences of unbalanced power. First, the economists tapped a database of millions of events involving the governments of two trading partners, confirming that negotiations and other forms of engagement increase with the asymmetries Hirschman described.

Another dataset, sourced from international opinion polls, was used to gauge bilateral geopolitical alignment over time and to verify a second predicted consequence. Yang and Liu found national leaders strategizing to build and bank trade power — by limiting imports, for example — when relations with a trading partner turned frosty due to political turnover.

“While many of the examples we give in the paper are from China, we hope to show this is a more general phenomenon,” Yang said. “Trade is a source of power any country can access.”

The paper is threaded with other insights.

“If the European Union acted as one country, it would actually be able to exercise positive power over China,” Yang said. “But individual EU members all have negative power over China. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that China typically engages with EU members bilaterally.”

What’s more, the U.S. and China are weaker against each another. The paper features a pair of maps illustrating their trade power over the rest of the world from 2001 to 2021. U.S. strength appears to peak in North America, while China’s is anchored in the Asia Pacific region.

“In terms of global power dynamics,” Yang observed, “medium-sized countries are very much the ones that get bullied.”

The results underscore a recent shift in the global trade order. For half a century following World War II, Yang said, the largest economies imported and exported with hopes of maximizing efficiency for the benefit of domestic businesses and consumers.

“What’s worrisome is that we’re starting to see the opposite,” he offered. “Trade is being restructured to take power into consideration. But in contrast with the positive-sum nature of efficiency-enhancing trade as countries produce according to their comparative advantage, power consideration in trade is negative-sum, hurting welfare on both sides.

“As we begin to painfully realize,” Yang added, “it may not be geopolitically feasible to implement efficient trade.”