‘Shed the tears … get up and fight some more’

Radcliffe Dean Tomiko Brown-Nagin (left) presents Associate Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court Sonia Sotomayor with the Radcliffe Medal.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Justice Sonia Sotomayor on importance of civic engagement, youth involvement, giving back

Part of the Commencement 2024 series

A collection of stories covering Harvard University’s 373rd Commencement.

Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor shared a little secret with the audience at last week’s Radcliffe Day: Despite the many ups and downs of recent court rulings, the power still ultimately belongs to the people.

“I can’t change laws — that’s not my job. I can only tell you what the law says,” she said. “It’s the voice of people, of constituents, that can change laws that you think are unfair.”

Sotomayor, who received this year’s Radcliffe Medal in a ceremony last Friday, detailed the importance of civic engagement and education in her address, and the responsibility of older generations to ensure these values are passed along. She began with a recounting of how she came to pursue a career in law and how it began with her own mother’s high expectations.

Born in the Bronx, she was the daughter of Puerto Rican immigrants and lost her father at a young age. Her mother instilled in her a tenacity to pursue education — and pushed her to dream big. Working tirelessly to pay for private schooling, her mother was a driving force in her life.

“Everything that I am that’s good is a legacy to my mother,” she said.

Sotomayor, a high school valedictorian, attended Princeton University, then Yale Law School, where she was an editor of The Yale Law Journal. She began her career working for Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau and later entered private practice. In 1991, Sotomayor was picked for the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York by President George H.W. Bush; to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit by President Bill Clinton in 1997; and to the Supreme Court by President Barack Obama in 2009.

She almost turned down Obama’s offer to ensure she would be present as her mother’s health declined.

“I was hesitant saying yes to President Obama because I was worried I would have less time to spend with her,” she said. “[My mother] said, ‘Don’t you dare not do this because of me. You would take away the dream I spent my life building. I wanted you to be the very best you can. You must take that job.’”

“[Sotomayor] broke barriers as the first Hispanic and first Latina to serve on the nation’s highest court,” said Dean of Harvard Radcliffe Institute Tomiko Brown-Nagin. “She’s been a fearless and insightful interpreter of our laws and Constitution. Justice Sotomayor is known for her incisive decisions and for rendering her analyses in clear and powerful prose.”

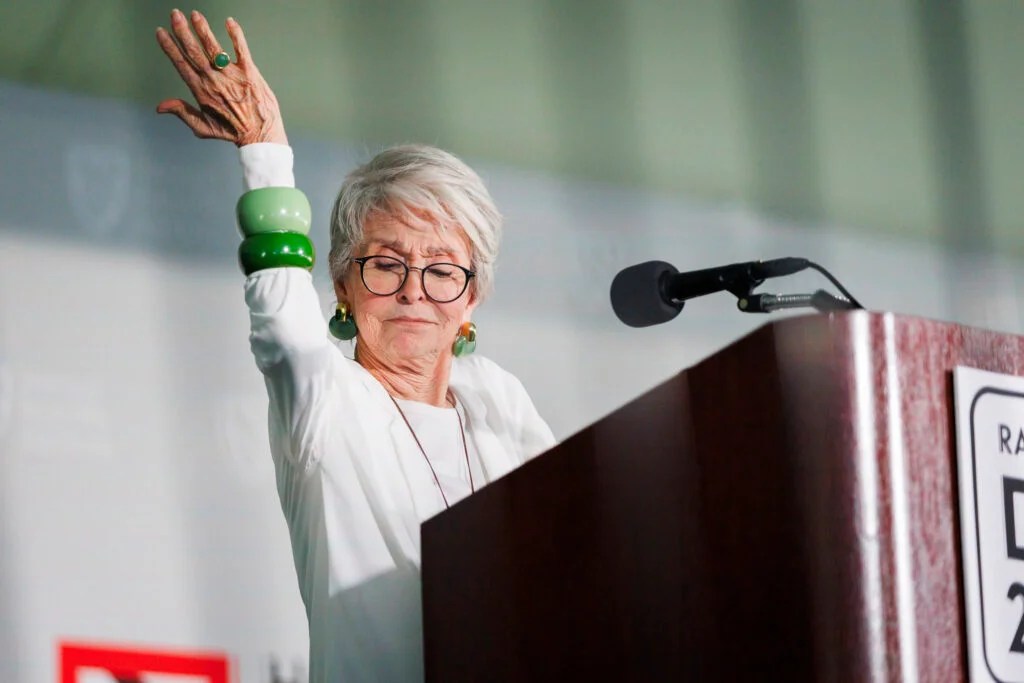

Rita Moreno, who in her 80 years as a performer has won an Oscar, a Tony, two Emmys, and a Grammy, introduced the justice. She said the two have been friends for a decade and that she has been struck by the judge’s ability to “remain profoundly human in the face of inhumanity” and that she’s a force that will continue to inspire others.

“Behind that robe and gavel lives a woman just as human and relatable as anyone else,” Moreno said. “Her compassion matches her legal acumen; her ability to see the people behind the cases and recognize the pain and humanity they live through has always set her apart.”

Sotomayor spoke of the many people who helped her along the way. In a space predominantly occupied by men, she said that “men stepped up” to become her mentors and help guide her.

And when she joined the U.S. Supreme Court, she found trailblazers such as Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O’Connor to support her. Sotomayor saw how much these women poured into others, and it inspired her to do the same — particularly with students and other young people.

“We adults have taken the world and messed it up. We are leaving our kids a world filled with problems,” she said. “We’ve done some good, but the young generation has to be inspired to do a better job.”

But they also need to be prepared, she noted. The late Justice O’Connor noted that the rise in partisan politics correlated with a decrease in civic education investment. Today, the federal government invests only 5 cents per student in civic education, compared to $50 per student in STEM education. Sotomayor said that is why she joined the governing board of iCivics, which O’Connor founded in 2009 to address this issue.

She challenged the audience to try their hand at playing the iCivics online education games “Win the White House” or “Do I Have a Right?” to test their own understanding of how government works.

Civics education also serves another purpose, she said. It teaches people how to talk about things that are difficult or on which they disagree. Disagreement doesn’t make people “evil or bad.” She said she should know, given the mix of the current court, a comment that garnered laughter.

“You may have different values, and you have to accept that. But every person has some good in them,” she said. “That’s what keeps me going. All these activities I do, I do to keep my spirits up, to give me hope about the future, to let me keep believing that we can make a difference.”

The Radcliffe Medal is awarded annually during Commencement Week to an individual who “embodies its commitment to excellence and impact.” It was first awarded to Lena Horne in 1987, and past recipients include Madeleine Albright, Hillary Rodham Clinton, Melinda French Gates, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Dolores Huerta, Sherrilyn Ifill, Toni Morrison, Sandra Day O’Connor, Gloria Steinem, Ophelia Dahl, and Janet Yellen.

Before Sotomayer took the stage, a multigenerational panel of activists, scholars, and attorneys took part in a panel discussion titled “The Long Arc of Equality and Justice in America.”

A common theme was the importance of engaging youth in some of society’s most pressing issues. Jerome Foster II, a 22-year-old climate activist, social entrepreneur, consultant, and speaker, noted that younger generations are finding ways to bring about change that include holding elected officials accountable.

“As young people, we’re coming together and saying, ‘You have to really have a moral awakening, where there’s a sense of clarity and purpose to you being in office and using that [position] you have for actual good,’” he said.

During the event, Sotomayor shared the stage with Martha Minow, the 300th Anniversary University Professor and a former dean of Harvard Law School. Minow asked Sotomayor whom she envisions as her audience when she writes her decisions.

Sotomayor said that it’s often for the general public, to explain her thoughts in a way that someone who is not a legal expert can understand. But she also writes them for people who might have the power to “make a difference for the positive”: lower court judges who might be able to think more broadly about a decision; the executive branch, which has powers she does not; or Congress, in hopes that it will correct a ruling the Court got wrong.

But for whoever reads her opinions, she’s hoping that people will be reminded of the power we all have as citizens.

“Throughout our history, men and women have given up their lives to secure our freedom and to promote our equality. There is no one in this room who is entitled to give up now,” she said.

When asked how she stays “eternally optimistic,” Sotomayor said she has her moments when she goes into her office, closes the door, and weeps. What then?

“You have to own it; you have to accept it; you have to shed the tears; then you have to wipe them and get up and fight some more,” she said.