How friends helped fuel the rise of a relentless enemy

ARLINGTON, VIRGINIA – SEPTEMBER 27: Photos of fentanyl victims are on display at The Faces of Fentanyl Memorial at the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration headquarters on September 27, 2022 in Arlington, Virginia. The Justice Department today released results of enforcement initiatives that they say has resulted in the seizure of the equivalent of 36 million lethal fentanyl doses from May 23 to September 8. Fentanyl is a synthetic opioid 50 times more potent than heroin, according to the Justice Department. (Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images

Economists imagine an alternate universe where the opioid crisis peaked in ’06, and then explain why it didn’t

The U.S. opioid epidemic is a story of failed policy initiatives, missed opportunities, and more than 600,000 deaths. It’s also a story with no end in sight, and for that, two economists say, we can blame relationships.

The central problem owes to the nature of the market, according to David Cutler, the Otto Eckstein Professor of Applied Economics at Harvard, and former Harvard doctoral student J. Travis Donahoe, co-authors of new research focused on the persistence of the crisis. In a situation with ample buyers and sellers — what economists call a “thick market” — spillovers in demand for opioids stem from the social nature of drug use, in which users encourage friends, acquaintances, and others to join them.

Information on opioids spreads easily via social networks

Illustrations by Liz Zonarich/Harvard Staff

Ample supply means acquiring opioids, sometimes from family, friends, is easy compared with other illicit drugs

Users encourage others to use

Epidemic expands, with more opioid users and rising deaths

These demand-boosting spillover effects are common when the pleasure derived from a good is enhanced by shared moments, such as drinks at the bar or a group outing to a sporting event, said Cutler. The effects are particularly strong when the good is also highly addictive, he added.

Like many others, Cutler has been horrified by the explosion of opioid abuse in the U.S., which in the 30 years covered by the study, 1990 to 2020, claimed more than a half million lives. At the same time, he’s been puzzled by the epidemic’s decades-long staying power, which far exceeds that of similar crises in U.S. history, including the crack epidemic of the 1980s.

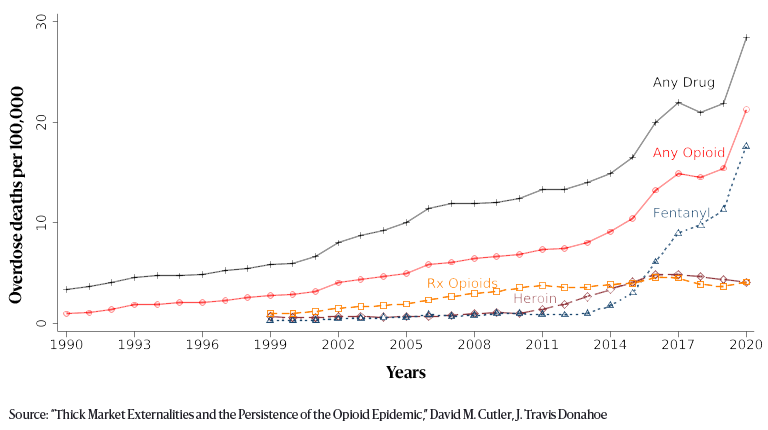

Trends in drug and opioid overdose deaths per 100,000, 1990 to 2020

Cutler and Donahoe, now an assistant professor at the University of Pittsburgh, note in the study that communication via social networks becomes especially important in an illegal market, where advertising is unavailable and open sale is prohibited. In addition, they say, the presence of a robust market with many users can lower the nonmonetary costs of obtaining drugs, like risks from law enforcement or of violence from drug dealers, because the likelihood of doing business with friends, family members, and acquaintances rises.

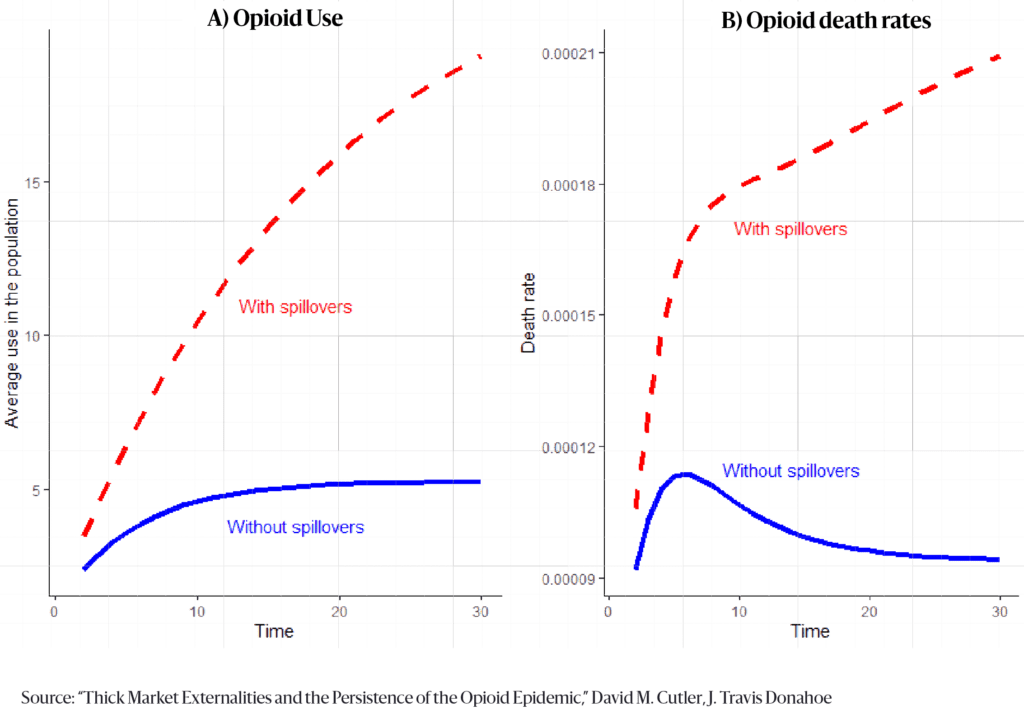

According to the analysts’ economic models, “spillovers” were responsible for between 84 percent and 92 percent of opioid fatalities from 1990 to 2020, and were the chief reason for the steady climb in deaths. Without that spillover effect, they wrote, the opioid epidemic would have peaked in 2006. In contrast, rising demand due to spillovers can be high enough in some scenarios that, absent effective intervention, deaths rise indefinitely.

Before zeroing in on spillover effects, Cutler and Donahoe examined other potential explanations for the persistence of opioid demand in the U.S., including “deaths of despair” factors such as physical and/or mental distress in the population. The pair, whose work is sponsored by the National Institutes of Health and the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality, found a modest impact at most. From 1999 to 2018, the prevalence of physical pain in the population increased 20 percent, while opioid deaths increased 400 percent.

A hypothetical opioid epidemic with and without spillovers

Similarly, the authors examined whether changes in supply might be sustaining the epidemic, which has been fueled at different moments by prescription opioids, illegal heroin, and, most recently, the synthetic opioid fentanyl. While supply has shifted significantly, Cutler and Donahoe point out that neither heroin nor fentanyl are new. Heroin has been around for more than a century and fentanyl for decades. It is the widespread use of these substances, not their availability, that has changed.

In addition, when the pair examined prices for illegal drugs, they found no evidence of a game-changer. Heroin prices remained relatively static even after the crackdown on prescription drugs, when more people sought out heroin. Similarly, fentanyl’s displacement of heroin represented a major change to the opioid supply. But, while fentanyl is much cheaper to produce, the price on the street isn’t that different from the price of heroin. This means that fentanyl makers are pocketing the difference rather than passing along savings to customers in a way that might boost demand, Cutler said.

The spillover effects at the heart of the epidemic are outgrowths of what economists call a “thick market”— in this case, one that developed early. Opioids have long been recognized as powerful painkillers but through most of the 20th century they were largely reserved for people with significant, acute pain, such as cancer patients. In the 1990s, prescribing practices shifted, so that the pain threshold dropped while the duration of use rose, creating a massive new market. One key driver was the time-release opioid OxyContin, which was promoted as safer and less addictive than other opioids. The rapid expansion of opioid prescribing created a veneer of safety and legality that increased societal acceptance of opioid use. Addiction was fed by “pill mills,” where prescriptions were written in volume.

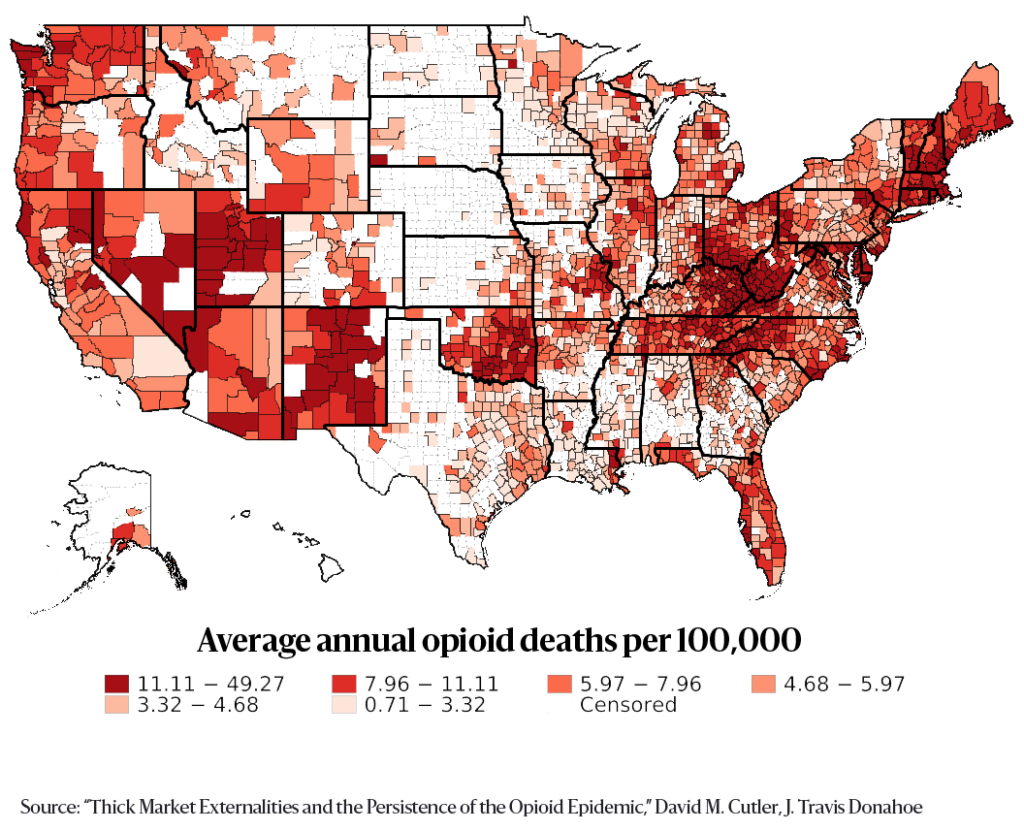

Map of average annual opioid deaths per 100,000, 1990 to 2018

“When the product is more readily available, other people use it more,” Cutler said. “The way people would get their start is they’d have some pain — back pain, knee pain — and they’d be talking to friends and family and someone would say, ‘Oh, when I had pain the doctor gave me opioids and I still have some in my medicine cabinet.’ So, here’s this prescription medication, and it’s got to be safe and effective or the FDA wouldn’t have let it out. The market is already there. I don’t have to do anything illegal. I don’t have to search very hard or go into the illegal market. The specific thing here is the availability. I can get it from friends, from family, from doctors who are prescribing it. That’s the sense in which the thick market makes it really easy to start off.”

The extraordinary potency of the drugs, he added, makes it extremely difficult to pull back.

“These are very, very addicting substances,” Cutler said. “They’re hugely addicting. That really matters because the withdrawal gets to be extremely severe and the consequence of that is that there’s a big issue in terms of people’s absolute desire to go back and use again.”

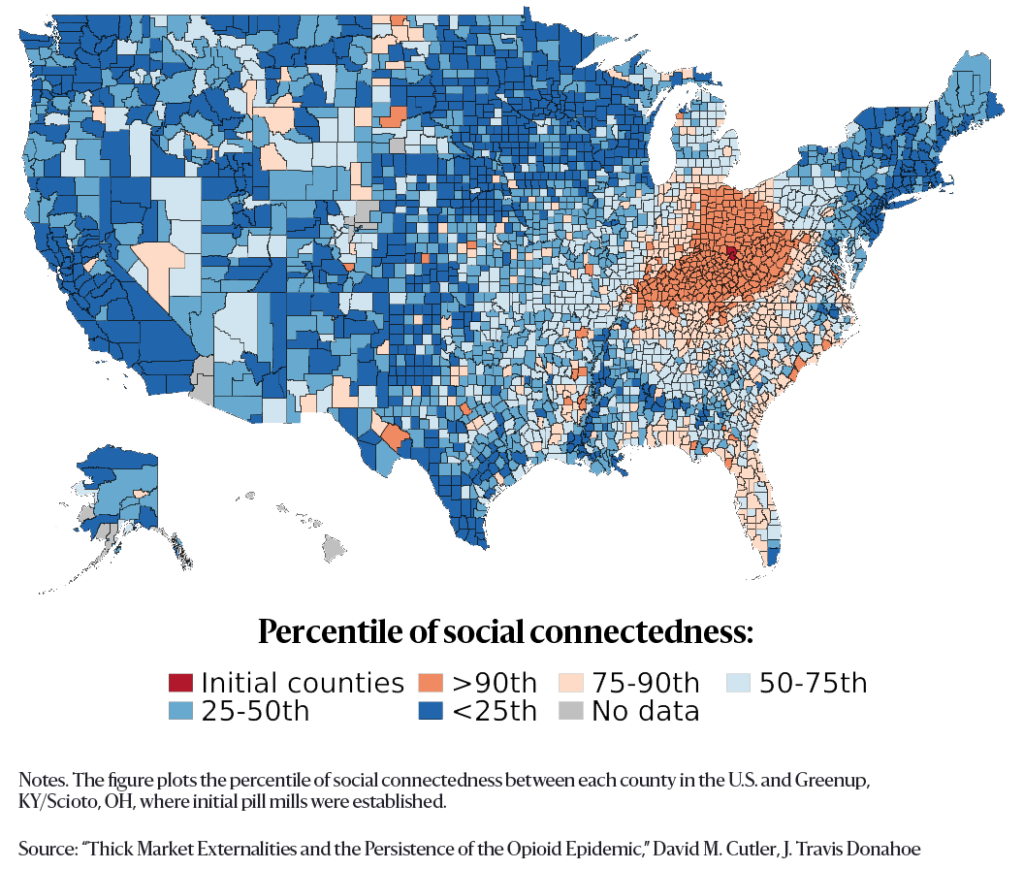

Cutler and Donahoe examined two pill-mill counties, one in Kentucky, the other in Ohio, where physicians prescribed opioids after cursory examinations, making them attractive for buyers interested in recreational use. The authors found that both physical proximity to the pill mill counties and social connectedness to people living in them raised the likelihood of opioid-related deaths. They found that every death in a pill mill county led to additional deaths in geographically close counties and in those with strong social connections to the pill mill counties, as measured by friend connections on Facebook.

Distribution of social connectedness to Greenup County, Kentucky, and Scioto County, Ohio

In this kind of “thick market” situation, the authors concluded, even temporary misconduct or mistakes by regulators and suppliers can create harms that far outlast the mistake or misconduct. And in this case, Cutler said, the fault lies with just about everyone.

“Companies got away with literally killing people,” he said. “The DEA screwed up, the FDA screwed up, medical societies screwed up, rating agencies screwed up. There’s enough blame to go around.

“If somebody had done their job really well — the FDA, the DEA, pharma companies, distributors, pharmacies — if someone had stepped in and said, ‘No, this is not right,’ the epidemic would have been less bad.”

To emphasize the point, he highlighted a missed opportunity amid the shift from prescription opioids to heroin. As authorities reacted to the damage of the growing crisis by tightening prescribing practices, they paid too little attention to demand. That failure to help, including a woefully inadequate commitment to treatment programs, led many people who were hooked on pills to turn to heroin.

“A big policy failure is that we thought too much about the supply side and not enough about the demand side,” Cutler said. “By coupling the supply side with the demand side, you would not push people into the illegal market, even as you make it harder for new people to get opioids when they don’t need them. Then, if you find a way for those who are addicted to get over the addiction, you’ve reduced demand. You’ve got a great glide path: fewer opioids out there, fewer new users, and help for those who are addicted.”

It’s a lesson that could still make a difference, he added — but only if we act on it.

“For the good of society, we’re treating opioids as more of a public health issue than a criminal issue. We got part of it right. There’s no sense putting people who are addicted to heroin or fentanyl in jail. That’s just dumb. But on the other hand, we can’t not help them out. The sad part is that we haven’t provided enough help.”