Now, what’s all this nonsense about age?

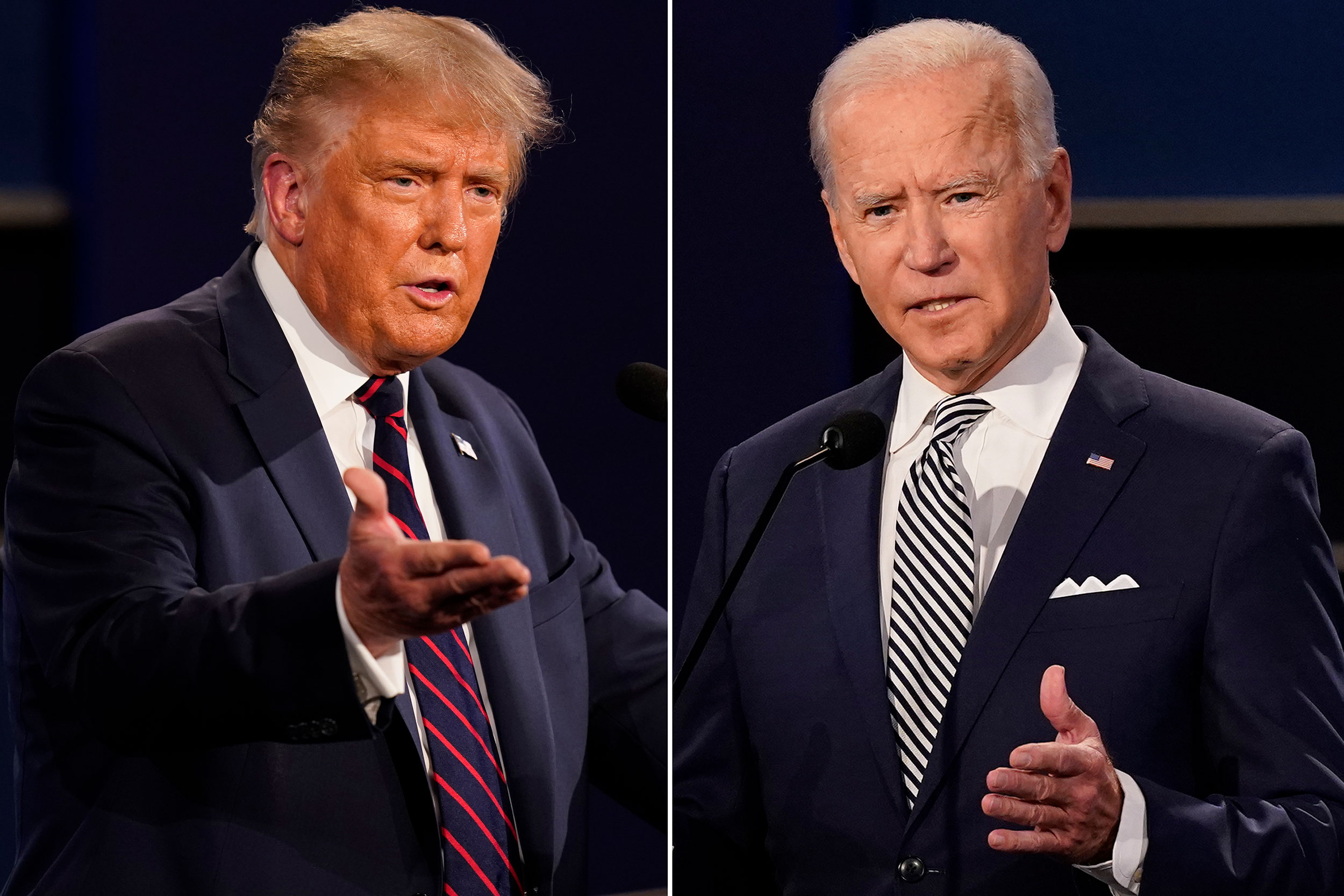

Donald Trump and President Joe Biden.

Patrick Semansky/AP Photos

Experts say both Biden, Trump operate at high level of competence, nation needs to drop stereotypes, embrace ‘longevity dividend’

Perhaps the most fevered political argument right now is over which leading candidate racks up more memory lapses and misspoken words, but experts on aging and cognitive decline say the debate misses a key point: Both men perform at an extraordinarily high level despite their advanced years.

And that, experts say, represents a missed opportunity to highlight the potential for the nation’s rapidly growing elder population to remain engaged, contribute to society, build on cognitive strengths that come with age and experience, and mentor a younger generation.

“It’s harmful because it sensationalizes and exaggerates certain negatives,” said Bruce Yankner, professor of genetics and of neurology and co-director of Harvard Medical School’s Paul F. Glenn Center for the Biology of Aging Research. “It’s important to be very engaged as people get older. And some people are perfectly capable when they’re Joe Biden’s age or beyond. They shouldn’t retire if they enjoy their work, and it’s fulfilling.”

At a time when Americans are living longer, workers are scarce, and the Social Security and Medicare safety nets are strained, it’s important that society take advantage of what researchers call the “longevity dividend,” according to John Rowe, professor of health policy and management at Columbia University, onetime professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, and former chairman of health insurer Aetna Inc.

“There is an innate negative view of older persons as less functional and impaired physically, sexually, and cognitively that represents an impediment to making progress and engaging older persons in our society so that they can really be productive,” said Rowe, who also has served as chief of gerontology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center. “By that, I mean not just work for pay, but volunteering, or many kinds of interactions. So, the focus on cognitive impairment is really taking the oxygen out of the room in terms of discussion about aging.”

16.8% Of U.S. population 65 or older in 2020 vs. 4.7% in 1920

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the proportion of Americans 65 years old and older has grown steadily since the beginning of the 20th century. Roughly 4.9 million Americans were 65 or older in 1920, comprising about 4.7 percent of the population. In 2020, there were 55.8 million Americans age 65 and older, about 16.8 percent of the population.

And the pace is picking up. The nation saw the largest-ever spike of people 65 and older from 2010 to 2020, rising 15.5 million, or nearly 4 percentage points. The aging trend is expected to continue in the coming decades as the remaining Baby Boomers turn 65, and behind them still is the nation’s largest generation — Millennials born between 1982 and 2000.

Rowe said that the public spotlight on the candidates’ age and cognitive ability plays on enduring stereotypes, which are inexorably and universally declining. While the incidence of physical conditions like diabetes, cancer, and cognitive decline do increase with age, Rowe said there is enormous variability in how well people age.

While an HMS professor, Rowe studied a cohort of 75-year-olds in East Boston, following their physical and behavioral characteristics for six years. By the time they reached 80, he said, there were distinct differences among them, with about 25 percent largely the same, 50 percent experiencing declines, and the final 25 percent doing poorly.

“There was a tremendous fanning out of their performance,” Rowe said. “We took that best 25 percent, and we labeled them as ‘super-agers’ because they were functioning at a very high level. You have to say that anybody who can be president of the United States, fly around in an airplane, and show up the next morning to debate with reporters is functioning at a high level. I would put him [Biden] in that category. You could probably look at Donald Trump, and you could probably say the same thing about him. He’s showing up every day, and he’s bringing it.”

While cognitive decline is a real threat, the current debate ignores the fact that aging also brings cognitive strengths, including reduced impulsivity, emotional steadiness, and reliability, all factors that might be viewed as positives in someone with a finger on the nuclear trigger.

“They have a lot to contribute through judgment, experience,” Yankner said. “People tend to be more contented as they age because they’ve seen a lot. They tend to minimize the negative more than when they were young. They accept limitations and use their experience to compensate. They set reasonable goals. They’re more likely to mentor other people as they reach this stage in life.”

Studies of age-selected teams in the business world compared younger workers against teams comprised of older workers and those with a mix of both. The mixed teams came out ahead, Rowe said, because they were able to leverage both the speed and nimbleness of youth and the steadiness and experience of age.

“They get a measure of speed, but they also get a measure of fewer errors and higher quality due to these characteristics of older people,” Rowe said. “We have this very large generation of older people with all this wisdom and experience. We need that in our society, rather than them just going to a nursing home or playing golf. We’re walking away from a lot of social capital, which has also been referred to in the literature as the ‘longevity dividend.’”

Concerns about the ages of Biden, 81, and Trump, 77, have been features of past campaigns — both have spent time as the oldest presidents in U.S. history. The recent furor was sparked by unflattering comments in special counsel Robert Hur’s report on Biden retaining classified documents in his home. In it, Hur concluded prosecution wasn’t warranted but characterized Biden’s memory as “significantly limited,” saying a jury might view him “as a sympathetic, well-meaning, elderly man.”

The comments were leapt upon by Biden’s political opponents, but Yankner and Rowe said whether what Hur observed is a sign of meaningful cognitive decline is hard to determine from a distance. But they also noted that nonexperts like Hur aren’t qualified to make a diagnosis.

“It’s one thing to say that somebody may have forgotten something here or there,” Yankner said. “It’s quite different to say they have significant memory impairment, with the implication that they’re unable to function effectively in their current capacity, on the job or at home. The universal of aging is that we all get there eventually, so always ask how you would like to be assessed at that point.”