Champion, creator of American theater

Robert Brustein, founder of rep companies at Harvard and Yale, recalled as teacher, critic, mentor, innovator

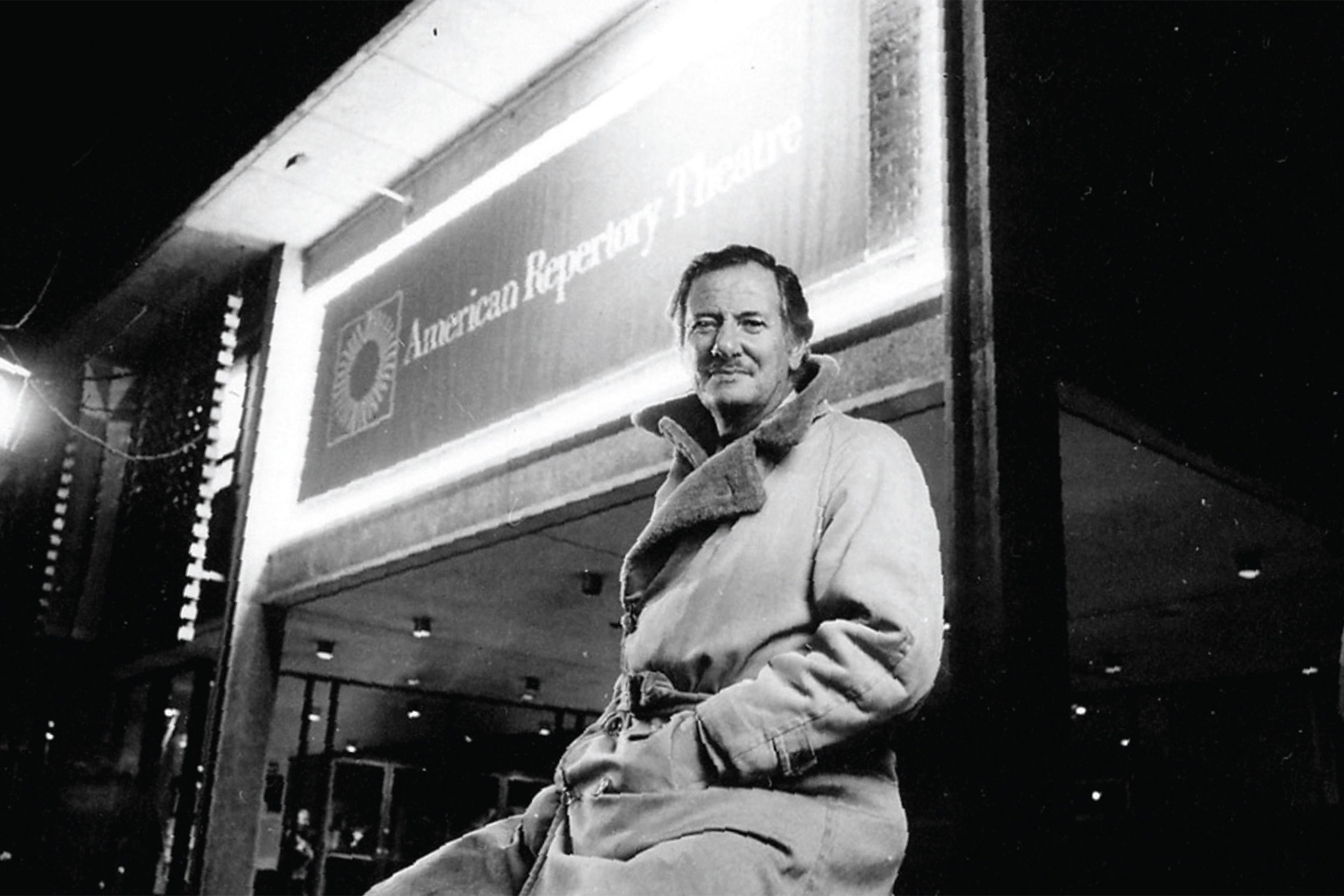

Harvard file photo

When Robert Brustein died on Oct. 29 at the age of 96, he left behind a legacy as a teacher, playwright, critic, occasional actor, and author. But central to the pugnacious longtime Cambridge resident was his role as an innovator and creator of theater, notably at Yale and Harvard, where he founded the American Repertory Theater in 1980 and served as its artistic director until 2002.

Early in his long career Brustein became a champion of vibrant nonprofit theater unafraid to embrace new plays, playwrights, and forms. His vision of American theater involved the proliferation of local companies across the country, each with its own independent voice, existing apart from what he viewed as the stifling, monied New York drama scene.

“Bob was one of the major forces that created the regional theater movement,” said Diane Paulus ’88. The A.R.T.’s Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director praised the theater founder’s “bold, innovative theatrical vision.”

Robert Sanford Brustein, born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1927, made his way through academia on his way to Cambridge. A graduate of New York’s High School of Music and Art and Amherst College, he earned an M.A. in dramatic literature from Columbia University.

But while he taught at Columbia, Vassar, and Cornell, publishing his influential book on “The Theatre of Revolt” along the way, his first major role in theater came in 1966, when he was named dean of the Yale School of Drama. Charged with revitalizing the school by Yale’s then-president, Kingman Brewster, he opened it up to undergraduates, broadened its scope to include literature of the theater, and founded the Yale Repertory Theatre.

“Bob was one of the major forces that created the regional theater movement.”

Diane Paulus ’88, A.R.T.’s Terrie and Bradley Bloom Artistic Director

With its focus on new works, including those by emerging playwrights, the Yale Rep established a challenging new model for repertory theater, one that would later form the basis for the A.R.T.

It was as an undergraduate at Yale that A.R.T. trustee Bob Murchison first became aware of Brustein’s work. “He insisted that a play, whether new or ancient, is not a fixed canvas, and requires interpretation by the artists,” said Murchison.

That relationship lasted until 1978, when the new president at Yale, Bartlett Giamatti, declined to renew Brustein’s contract, and in 1980 Brustein came to Cambridge. At Harvard, he would serve as a professor of English, director of the Loeb Drama Center, and founder of the Institute for Advanced Theater Training.

He also became the artistic director of what would soon evolve into the A.R.T., which launched later that same year with a production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” (Brustein played the role of Theseus.)

Karen MacDonald, a Boston-area actor, was part of the A.R.T.’s company from its inception in 1980 until 2010. “It was very exciting to be a part of this new venture that was taking place at the American Repertory Theater at Harvard,” she recalled. “[Brustein] was putting together a group of people, both onstage and offstage, directors, designers, and the folks who worked backstage with us.

“We bonded very quickly and became a real company,” she said. “I wouldn’t have met my husband if it wasn’t for Brustein.” Her spouse, David Remedios, served as head of the A.R.T.’s sound department.

Brustein founded the A.R.T. in 1980 and served as its artistic director until 2002.

Courtesy of American Repertory Theater

The repertory model, favored by Brustein, involved a resident company doing plays in rotation. It provided an unusual level of stability for an actor. “It represented a very different way of being able to work, such as having a seasonlong contract with a living wage that you could count on,” explained MacDonald. Many in the company — including MacDonald — were also given the opportunity to teach, following in Brustein’s footsteps.

“Not only does he leave an immense legacy in the theater, he changed the lives of so many of his students, whom he loved,” noted Sam Marks, senior lecturer on playwriting and Paul and Catherine Buttenweiser Director of Creative Writing.

At the same time, Brustein and the A.R.T. also challenged its members, MacDonald said. Recalling tours to England and Scotland as well as the former Yugoslavia during those first heady years, she remembers the young company working with European directors, an experience she described as “exciting and eye-opening. Seeing the way they approach the work, the way their culture and their theater traditions could be melded with ours.”

Back in Cambridge, one rapt member of the audience was Paulus, then an undergraduate. Although she had grown up with theater in New York, “I saw a theater that was truly putting a wedge in my brain about what the theater could be,” she said.

A.R.T. productions involved such innovative directors as Julie Taymor, Robert Wilson, Joanne Akalaitis, and Andrei Serban. “These were bold theatrical visions,” said Paulus, regarding his impact on her as an artist. “He was showing us all what was possible in the theater.”

Throughout his years at the A.R.T. and long afterward, Brustein continued as the drama critic of The New Republic, a position he began in 1959, and also occasionally waded into controversy. For example, the A.R.T.’s 1984 production of “Endgame,” directed by Akalaitis, drew a threat of legal action from playwright Samuel Beckett because its staging and casting differed from the playwright’s very specific directions. The eventual compromise meant including a scathing denouncement from Beckett, and the show went on.

Brustein himself picked a fight with both Yale Rep and the playwright August Wilson when Wilson’s “The Piano Lesson” moved from New Haven to Broadway. Such a commercial move, he said, was “a serious deterioration in the integrity and nature of the resident theater movement.” His further criticism of Wilson’s work resulted in a yearslong feud carried out in both The New Republic and American Theatre magazine, culminating in a “town hall” discussion in 1997.

Brustein would serve as the A.R.T.’s artistic director until 2002, when he was succeeded by Robert Woodruff. Paulus began her tenure in 2008, and (since June 2022) has co-led the theater with Executive Director Kelvin Dinkins Jr. Even after leaving Harvard, Brustein remained an influential voice in theater.

“The theater doesn’t have a required retirement age,” noted MacDonald. “As long as you keep seeking work and creating work and finding work, you can just keep going. And Bob was testimony to that because he was 96, and he still loved to talk about the theater. I don’t think he ever lost that passion and that commitment, and he passed that on to us.”

“His legacy is not only in all the artists that he took chances on and that he supported,” said Paulus. “For me, Bob’s impact was the playground he gave to all these artists. His legacy lives on in so many ways. As a playwright, as an artistic director, as a director, as a writer, as a critic, as a teacher.”