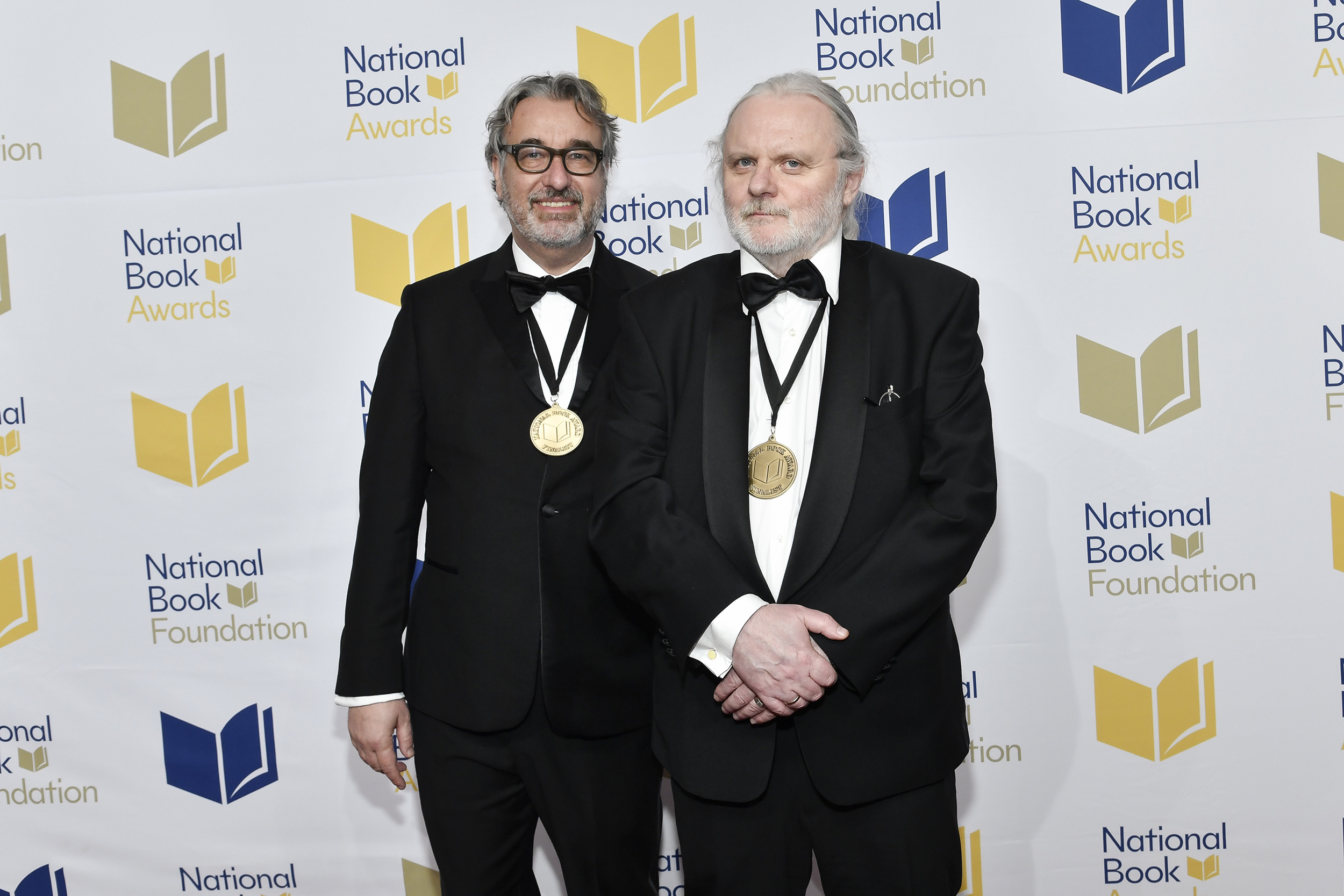

Damion Searls ’92 (left) with author Jon Fosse at the National Book Awards last year.

Evan Agostini/Invision/AP

How to translate a Nobel-winning author (and 700-page sentence)

Damion Searls — English ‘gateway’ for Jon Fosse and other writers — discusses Harvard roots, elevating new voices, and his multilingual ‘Matrix’ moment

When Damion Searls ’92 first read a novel by 2023 Nobel Prize-winning writer Jon Fosse more than 20 years ago, he had to read a German edition because he didn’t know Norwegian.

An American publisher had asked Searls to do a reader’s report of Fosse’s “Melancholy,” a fictionalized account of the life of a 19th-century Norwegian painter. But when the publisher ultimately decided not to pursue the project, Searls — who had found the book “absolutely brilliant and genius” — decided it was time to learn Norwegian, enlist the help of a Norwegian-born co-translator, and do the project himself.

Today Searls, who was a philosophy concentrator during his time at Harvard, has translated 10 of Fosse’s works, including his three-volume masterpiece “Septology I-VII.” His translation of “A New Name,” the third volume, was shortlisted for the 2022 International Booker Prize.

“I’m someone who believes that what a translator does is read really well and then write in English,” Searls explained. “You don’t have to be a fluent speaker of the language you’re reading. You don’t have to be able to interpret at the U.N. or order a meal in a restaurant, because that’s not the skill. The skill is reading a written book.”

Distinguished Writer in Residence at Wesleyan University, and a translator from German, Norwegian, French, and Dutch, Searls has translated many modern classic writers including Proust, Rilke, Nietzsche, Thomas Mann, Max Weber, and Ingeborg Bachmann. He also writes his own books in English, including “The Inkblots,” about the Rorschach test and its creator.

Searls wasn’t always multilingual. It wasn’t until he was a Harvard College senior, working on his thesis on German philosophers, that he began studying the language he now knows best besides English. And it wasn’t until the former Adams and Dunster House resident returned to campus in 2004 to teach in the Harvard Writing Program that he enrolled in an entry-level French course.

“It was like in ‘The Matrix’ where you hear all this clicking and everything fits together, from my past experience of seeing French movies with subtitles and thinking about language in general,” Searls said. “The second day, I transferred from French 1 to French 3.”

“You don’t have to be a fluent speaker of the language you’re reading. You don’t have to be able to interpret at the U.N. or order a meal in a restaurant, because that’s not the skill.”

Searls believes the key to a good translation is being able to write well in English, so the piece’s tone — whether it’s humor, sharpness, or anger — comes across in a natural way.

“When I tell people that I’m a writer — what I do is write books in English — it kind of blows their mind because they never think of translation that way,” Searls said. “But when you were 3 years old hearing stories about Cinderella or Poseidon, that’s translation. It’s just a story that happens to have been written in another language first.”

For years, Searls’ only communication with Fosse was via email, as the Norwegian writer and playwright was often busy traveling for his work. Fosse gave Searls free rein with most of the earlier books, but worked more closely with his draft translation of “Septology,” comparing it to the Norwegian text and making comments. The two met in person for the first time at the 2022 International Booker Prize ceremony in London.

“We had an email friendship, which I really treasure,” Searls said. “He’s very kind and wise and friendly and responsive and great.”

Searls believes Fosse’s books are universally beloved because they offer an experience that casts a spell over the reader. The books are also accessible, he added, due to their straightforward vocabulary and relatable characters.

Readers shouldn’t feel intimidated by the books’ reputation — especially “Septology,” which is known for its “slow prose” style and one single sentence lasting over 700 pages, he said.

“Some people are like, ‘Oh, I thought it would be difficult because I read all these reviews, but I read it straight through, it wasn’t hard at all,’” Searls said. “It’s not some incredibly difficult puzzle. There are a lot of sentences, they’re just divided by commas and ‘ands’ instead of periods. It’s just a different rhythm of putting the thoughts together.”

Searls says English is the most important gateway language in translation. Books will often spike in popularity after being published in English, and the ones that become most famous tend to be the ones that appeal the most to Americans.

Knowing the impact English translation can have, Searls has taken on some recent translation projects that introduce new, young, female voices, such as Norwegian writer Victoria Kielland, author of “My Men,” to the English-speaking world.

“Sure, retranslating Thomas Mann is introducing readers to a new voice and it opens him up to a lot of people who hadn’t read him before, but that’s different from a young living person getting to debut in English while they’re alive and it making a difference in their career,” Searls explained.

When asked if he feels a weight of responsibility being a “gateway” to the English-speaking world for many authors, Searls says he actually feels more pleased than pressured.

“I read the book and thought it was great and now, thanks to me, there are lots of other people who get to read this great book and think it’s great,” Searls said. “When I translate books that I really love and I hear from readers who are like, ‘Oh, my God, I love this book,’ I’m glad. I feel like I did my job, and I got to share this experience, which was meaningful for me.”