Erasing reminders of stigmatizing, traumatic past

Med School-MGH dermatologists use lasers to remove gang, trafficking tattoos

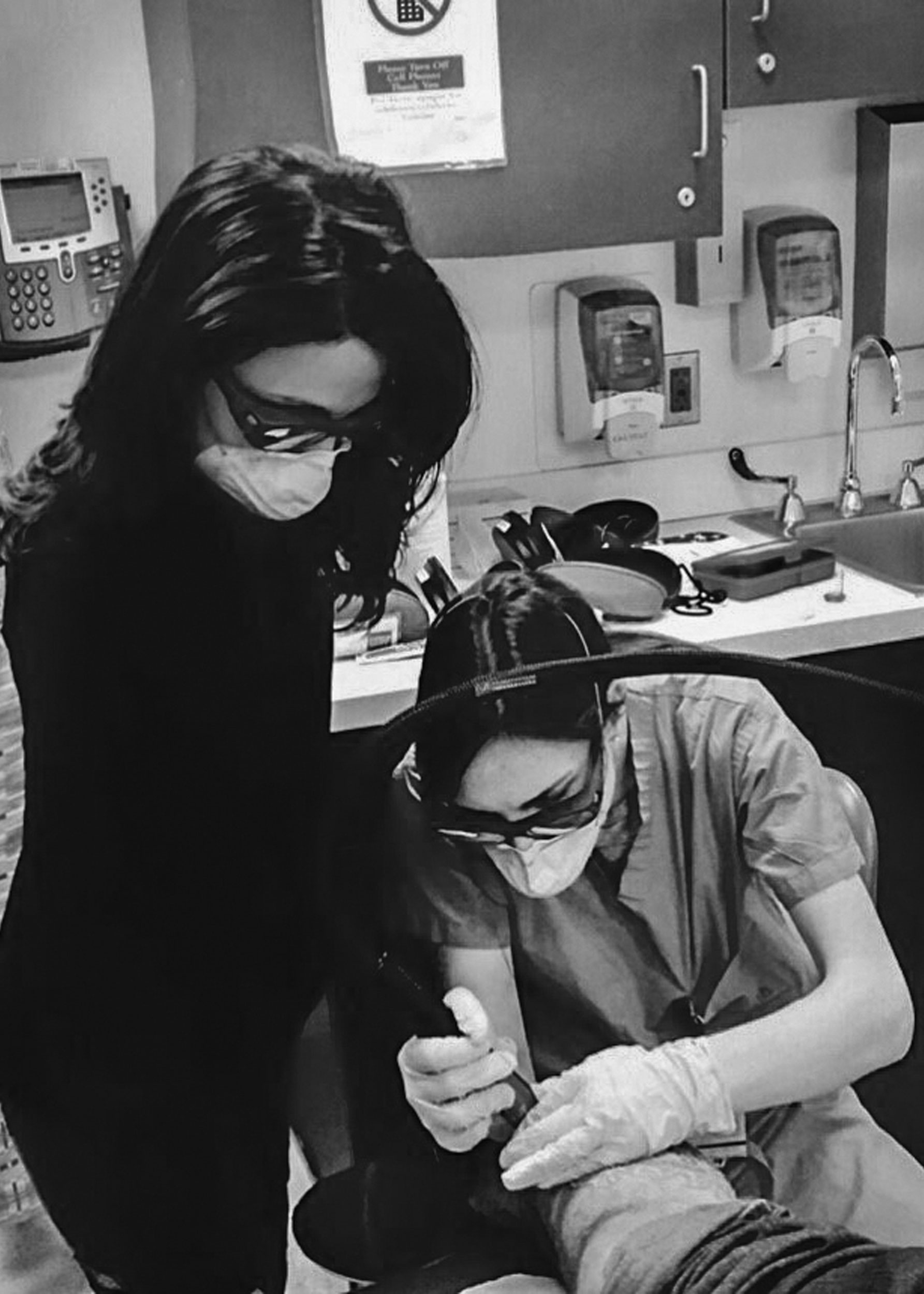

In her clinic, Shadi Kourosh (left) supervises dermatologist Rebecca Hartman on tattoo removal as part of the community program.

Images courtesy of Shadi Kourosh

Massachusetts General Hospital dermatologist Shadi Kourosh learned early in her career that some tattoos serve as a kind of covert branding, marking gang members or sex-trafficking victims. In 2014, Kourosh founded the Radiance Clinic, a laser tattoo-removal program to erase those enduring reminders on individuals seeking to forge a new life and escape past traumas. The clinic provides free care for patients and works in concert with primary-care physicians, law enforcement, and state prosecutors. Koroush, director of community health for MGH’s Dermatology Department and an assistant professor of dermatology at Harvard Medical School, spoke with the Gazette about the program and the patients.

Q&A

Shadi Kourosh

GAZETTE: How did you first become aware that tattoos had a sinister side?

KOUROSH: I learned the skills of laser tattoo removal by volunteering in a community program at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. I was in my dermatology training and took care of a young man who had escaped a gang and was getting very visible tattoos on his neck, arm, and hand removed because he was joining the Marines.

When I was recruited to Massachusetts General Hospital, Dr. Alexa Kimball asked me to found the Division of Community Health for dermatology to care for patients in a network of clinics in underserved communities of Boston. One is in Chelsea, which has the highest number of gangs per capita in New England. Doctors there care for people trying to get out of gangs and turn their lives around, and they asked if I could help. I had experience removing gang tattoos and thought, that’s a way that dermatology can contribute to these patients turning their lives around.

Medical laser experts Dr. Rox Anderson and Dr. Sandy Tsao guided and mentored me in founding the clinic. We kept the location of the clinic secret for the safety of our patients and our staff. Local primary care doctors knew about us through word of mouth, as did the nurse examiner from the district attorney’s office. We also established a positive working relationship with law enforcement, and early on we had a member of the New England Gang Unit give a presentation to our doctors, staff, and volunteers about recognizing gang tattoos.

GAZETTE: Are there common symbols used?

KOUROSH: When we started doing this work, the first call I got was from a local primary care doctor who knew that we were running a clinic to remove gang tattoos. He had a young woman who had been branded with tattoos due to human trafficking, and we agreed to help. Then the nurse examiner from the DA’s office called us and we started to develop relationships with local organizations that helped trafficking survivors.

We started to see themes, in both trafficking tattoos and gang tattoos, motifs of violence and weapons. Specifically for commercial sex trafficking, there are motifs like hearts or Valentines, things that convey romantic sentiment. There are also symbols of payment and ownership, and sometimes the name of a person will be branded onto a woman, as if that person owns her.

Location on the body is important. Gang tattoos are often in visible areas. The first young man I took care of had tattoos on the neck, forearms, and hands. I’ve seen tattoos on the face. They’re meant to be visible so that gangs or exploiters can identify the victim in daily life, as they walk around the community. In the case of commercial sex trafficking, sometimes the tattoos are in private areas.

“I’ve had human trafficking survivors that are retraumatized when they see the tattoos that they’ve been branded with in the mirror.”

GAZETTE: Are they generally applied against the person’s will?

KOUROSH: It depends. A group of women were kidnapped and drugged, and when they woke up, they all had the same gun image tattooed on them. That was the practice of that particular crime ring. When a person is under duress or coercion or manipulation, consent becomes a complex issue. We hear stories of traffickers having promised victims employment, education, liberty if they will cooperate, only for the victims to realize those things weren’t going to happen.

There’s also a misconception held by many — including in our medical community — that trafficking is a foreign, international issue. It’s far more domestic than many realize, and sometimes present in our own communities.

GAZETTE: How does tattoo removal help the victim?

KOUROSH: It allows the person to become safe, because having these brandings visible can make a person a target for recapturing, re-exploitation, or in the case of gang tattoos, a target for members of an opposing gang.

I had a patient who grew up on the streets, needed protection, and entered a gang at the age of 14. He escaped that life by the time he became an adult. He got an education, had a job and a family. One day, he was out walking and members of an opposing gang recognized the tattoo on his arm. They ran him over with a car, then beat him, and left him for dead.

He came to us and said, “You have to get this off of me. I’ll never be safe.” So safety is a major reason that people seek removal. Another reason — a practical reason — is acquiring jobs, some of which have requirements around visible tattoos.

It’s also a barrier to reintegration into society and can be an obstacle to healing from trauma. I’ve had human trafficking survivors that are retraumatized when they see the tattoos that they’ve been branded with in the mirror. They’re a reminder of what they’ve been through. One patient, a sex trafficking survivor who had a gun tattoo, would cry when she saw it. She hugged us and told us we had changed her life. So, an important part of healing from trauma can be having these brands removed.

GAZETTE: You have written that a lot of trafficking victims intersect with the healthcare system, but physicians and other healthcare workers miss the signs?

KOUROSH: When I started taking care of human trafficking survivors, I searched the literature for anything that could help our team better understand what was going on and how we could help these patients. But there was almost no literature in the medical community on this, and nothing in dermatology. I wrote a paper, with my medical students, on the skin signs of human trafficking that was the first in the dermatology literature.

There were a few other papers, in pediatrics, because pediatricians have to advocate for children, and in psychiatry. A group of psychiatrists were caring for patients’ trauma around human trafficking, but only after the victims had already gotten away, so they were calling upon their colleagues to develop some way of identifying these patients sooner.

As I was doing this research, I realized that the best paper that I could find with information on the medical problems affecting human trafficking survivors was written not by a doctor, but by a law professor, Laura Lederer. Her team went into shelters around the country, interviewed and did focus groups with human trafficking survivors. They asked if they had interacted with the healthcare system and a very high percentage — like 88 percent — were interacting, unnoticed, with the healthcare system.

When people ask me about this, I give them statistics that are quoted by the U.N. or the World Health Organization or our own Department of Homeland Security, but we bear in mind that, because of the hidden nature of these crimes, we may be looking at the tip of an iceberg.

GAZETTE: So, it’s difficult to assess because not everyone who gets out of a gang or escapes trafficking winds up in places where researchers can assess their numbers?

KOUROSH: There are a lot of barriers to having accurate and thorough information on this topic: the hidden nature of the crimes and not having an organized effort to gather information.

I chair a task force of the American Academy of Dermatology that has brought together dermatologists from around the country. We interviewed many experts, including Dr. Abigail Judge, who is a psychiatrist at MGH and a national expert on human trafficking. We created an online tool kit on the website of the American Academy of Dermatology that has information about recognition, about how to navigate an encounter when trafficking is suspected, and how to document information in the medical record in a way that protects patients’ privacy.

We are also gathering resources for doctors and patients so that they can be downloaded and shared whenever possible. It’s an ongoing effort, and we’re continually learning.

This is a human rights crisis and a public health crisis that has been ongoing for some time. We’re just beginning to understand its breadth and scope. It’s been heartwarming to see the response of my colleagues, how much they care, and how much they are willing to serve. We just need to give them the tools.