Turns out lowly thymus may be saving your life

Study suggests organ plays vital role in immune health, particularly cancer prevention

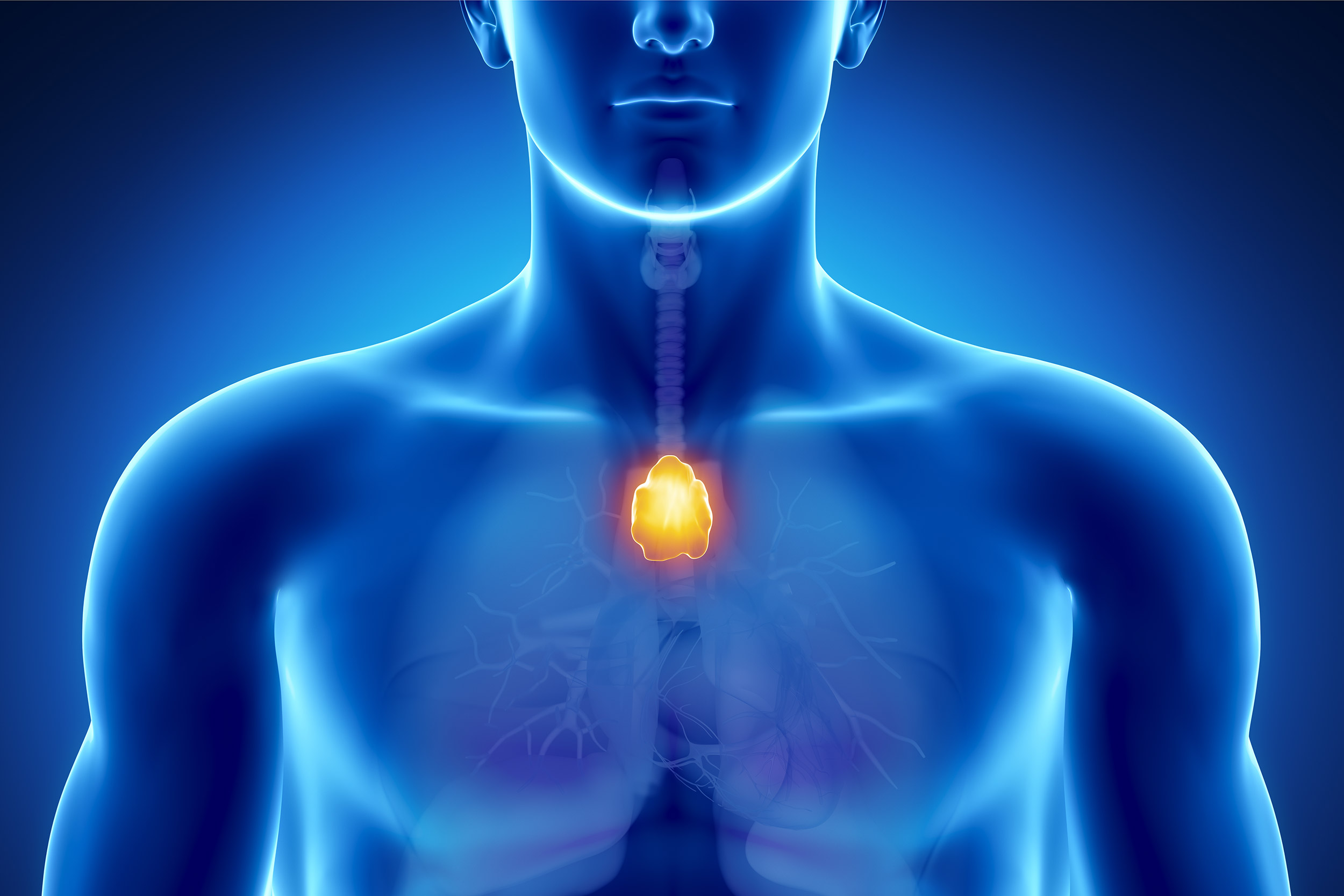

Many people couldn’t say where their thymus is, or what it does, and even doctors have long considered it expendable in adults. But new Harvard-led research suggests that the walnut-sized organ in the chest actually plays a vital role in immune health as we age, particularly in cancer prevention.

The study comparing data from patients who had their thymus removed with those who had not found that thymectomy patients had a nearly threefold higher risk of death from a variety of causes, including a twofold higher risk of cancer and a more modest increase in autoimmune diseases.

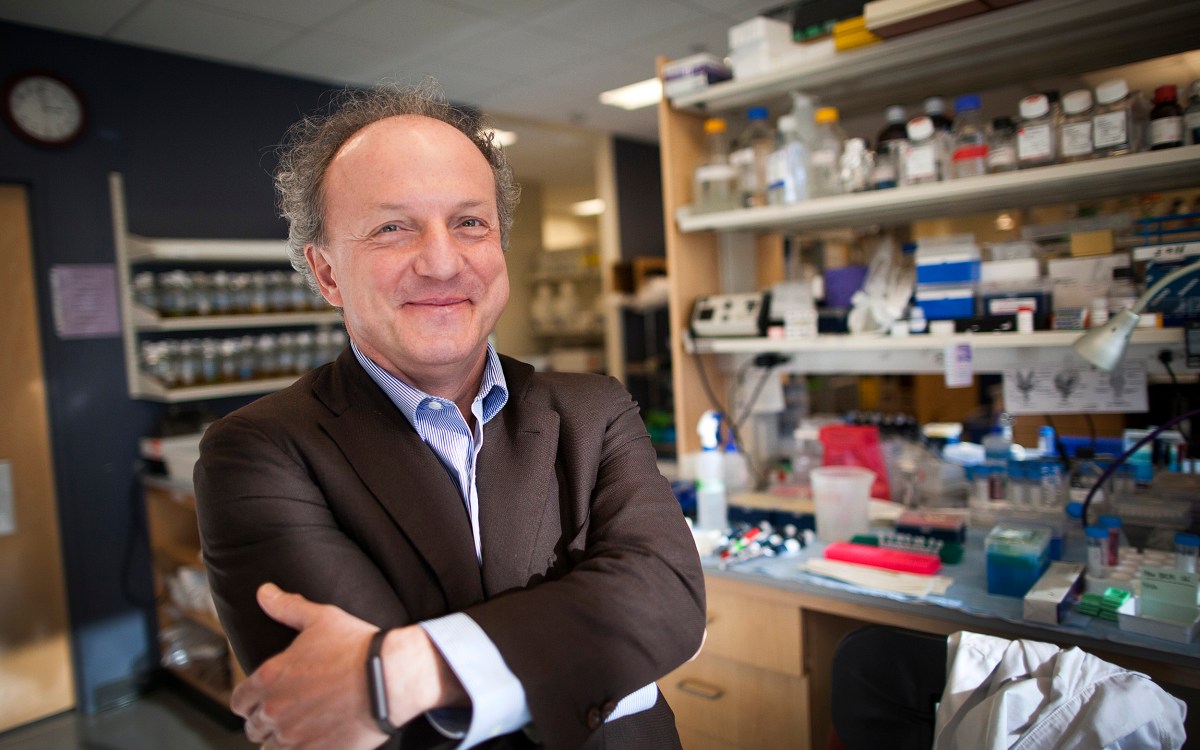

“The magnitude of risk was something we would have never expected,” said David Scadden, the Gerald and Darlene Jordan Professor of Medicine and professor in the Department of Stem Cell and Regenerative Biology, who led the study published in The New England Journal of Medicine in collaboration with researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The primary reason why the thymus has an impact on overall health seems to be as a way to protect against the development of cancer.”

The thymus is the fastest-aging organ, according to Scadden. Most active in churning out T-cells during early childhood, it begins to atrophy into fatty tissue around puberty. That’s why, for many decades, scientists assumed it served a limited purpose in adulthood. It is typically removed due to issues with the organ itself, such as thymus cancer, or during other cardiothoracic surgeries because it’s located in front of the heart and is often in the surgeon’s way.

Yet in recent years scientists had started to suspect that the thymus plays an outsize role in our health as we age, by continuing to make T-cells that contribute to the diversity of the body’s overall T-cell population.

“This study demonstrates just how vital the thymus is to maintaining adult health,” Scadden said.

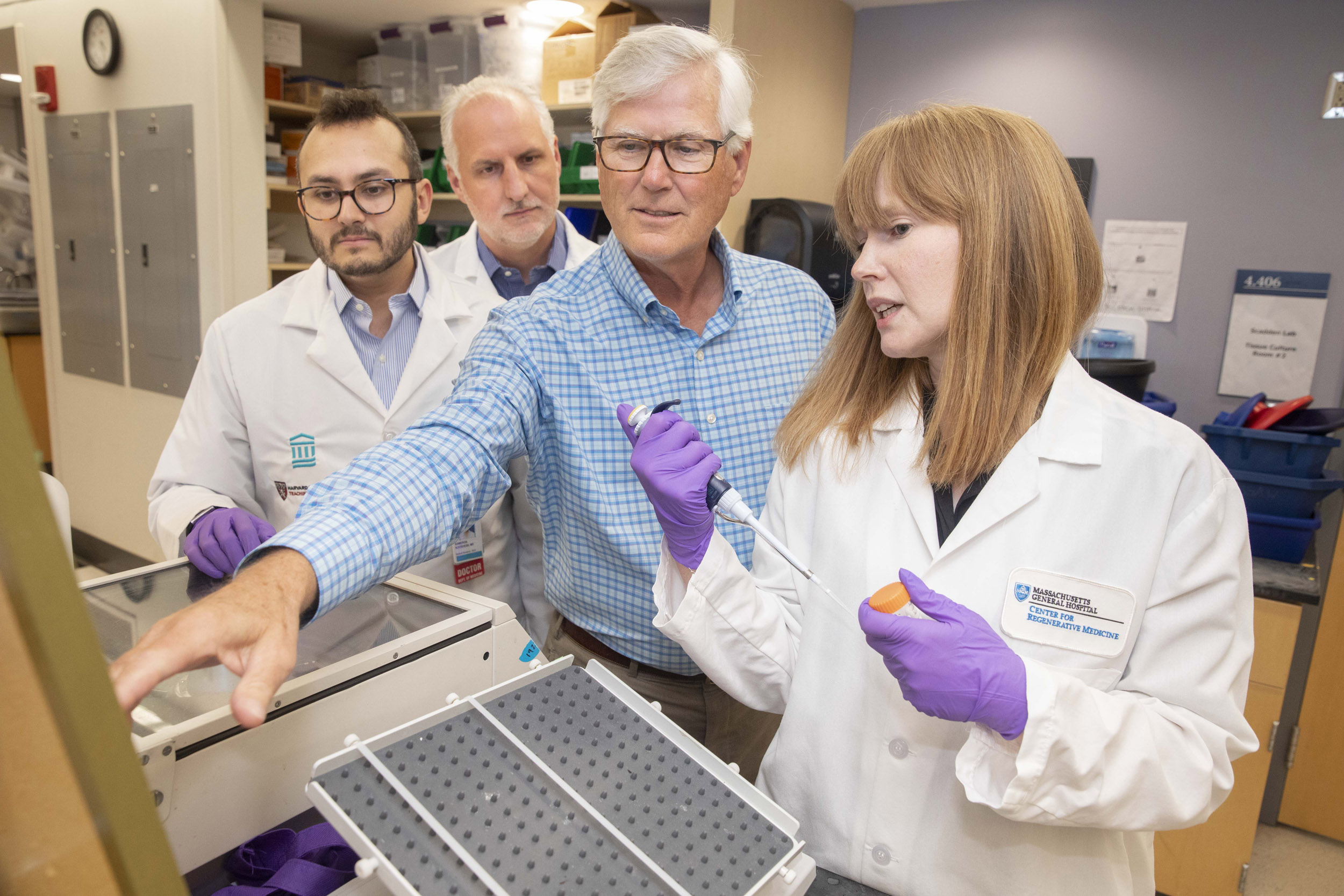

Kameron Kooshesh, (from left), David Sykes, David Scadden, and Karin Gustafsson at work in their lab at MGH.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

First author Kameron Kooshesh became intrigued by open questions about the adult thymus during a second-year neurology lecture at Harvard Medical School. He learned that surgical removal of the thymus is recommended in patients with the autoimmune disease myasthenia gravis as a way to halt T-cell-induced immune destruction of nerve endings. “And yet, clinical instruction on the surgery wards taught me that the thymus is thought to be vestigial in adults,” Kooshesh said. “These two philosophies seemed diametrically opposed, and I yearned to learn more.”

For the study, Kooshesh mined data from 1,146 adult patients who had undergone thymus removal, alongside demographically matched control patients who had undergone similar surgeries but kept their thymus. Kooshesh and Scadden worked in collaboration with Brody Foy, a biostatistician who helped direct the team’s statistical queries around the epidemiology of thymectomy patients, and Karin Gustafsson, an expert in T-cell biology. David Sykes at MGH helped the team facilitate patient blood draws.

In an analysis involving all patients with more than five years of follow-up, the rate of death was higher in the thymectomy group than in the general U.S. population — 9 percent vs. 5.2 percent, as was death due to cancer, or 2.3 percent vs. 1.5 percent.

In a subgroup of patients in whom T-cell production was measured, those who had had their thymus removed had less new production of T-cells, including both helper and cytotoxic T-cells. Those patients also had higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are small signaling proteins associated with autoimmunity and cancer, in their blood.

“The magnitude of death and cancer in patients who had undergone thymectomy was the biggest surprise for me,” said Kooshesh, now an internal medicine resident at MGH. “The more we dug, the more we found: The results suggested to us that the lack of a thymus appears to perturb basic aspects of immune function.”

The analysis was facilitated by recent advances in rapid genetic sequencing of T-cell receptors (TCRs). The technology, called TCR sequencing, has enough resolution to allow scientists to not only identify different types of T cells, but also measure their diversity as a population overall.

Funding for this work included support from the National Institutes of Health.