Getting a good group portrait can be difficult even today with advanced photo-editing tools at our fingerprints and infinite “takes.” Photographers in the 19th-century had to get creative.

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Murder, misguided creativity, and other tales in salt prints

19th-century photo technique — and stories of people in front of, behind camera — get new exposure as Harvard digitizes vast collection

The materials required for salt printmaking, the oldest negative-to-positive photographic technique, are simple: silver nitrate, cotton or rag paper, water, sodium thiosulfate, sunlight, and table salt. Yet salt prints — more fragile and prone to fading than other photo processes popular in the mid-1800s — are relatively rare, making Harvard’s collection numbering 12,300 one of the largest in the U.S.

Library patrons can now access much of the collection digitally thanks to a survey started in 2008 by Weissman Preservation Center specialists. What started as a project to identify the thousands of salt prints held by repositories across the University evolved into an initiative to preserve them.

Conservators Elena Bulat and Amanda Maloney prepare salt prints for digitization at the Weissman Preservation Center.

Over the years conservators have gotten to know the stories behind the prints as they’ve cleaned and stabilized them for digitization. The photographic subjects have histories, of course. But because Harvard holds so many of the prints, spanning from the 1830s to the late 1860s, the collection also illustrates the evolution of photography during a crucial time for the medium.

“There’s a lot of information available here, if you know how to read it,” said Elena Bulat, Paul M. and Harriet L. Weissman Senior Photograph Conservator.

By the mid-1860s, salt prints fell out of favor as albumen prints, which produced a sharper image, became the dominant technique.

Messy edges, messy affair

Few of the print subjects had as much drama swirling around them as did Teresa Bagioli Sickles.

Sickles was married to U.S. Rep. Daniel Sickles, who in 1859 became known as the “Congressman who got away with murder” for shooting and killing his wife’s lover, U.S. Attorney Philip Barton Key II. Despite the Congressman’s alleged many affairs of his own, he was acquitted after pleading temporary insanity, and public opinion turned on his wife. The image of Teresa Sickles, created around 1855, is part of the Portrait Collection at the Fine Arts Library, which includes more than 800 salt prints.

The edges of Sickles’ portrait tell a story of their own, said Special Collections conservator Amanda Maloney. A rectangle around the portrait shows where a glass plate was pressed onto the paper in a printing frame.

“We get a real sense of the physicality of that object,” Maloney said.

She pointed out sections of the paper near the edges with a lighter gray color or no coloration at all, marking where the light-sensitive silver salts, which would have been applied by hand by the photographer, stopped short.

This is unusual, Maloney said, since typically, “not only would a printmaker crop out the edges of the plate, but they’d crop out the edges of the paper.”

Coating and coloring: What were they thinking?

There are other prints in Harvard’s collections that raise questions as to the printmaker’s intent.

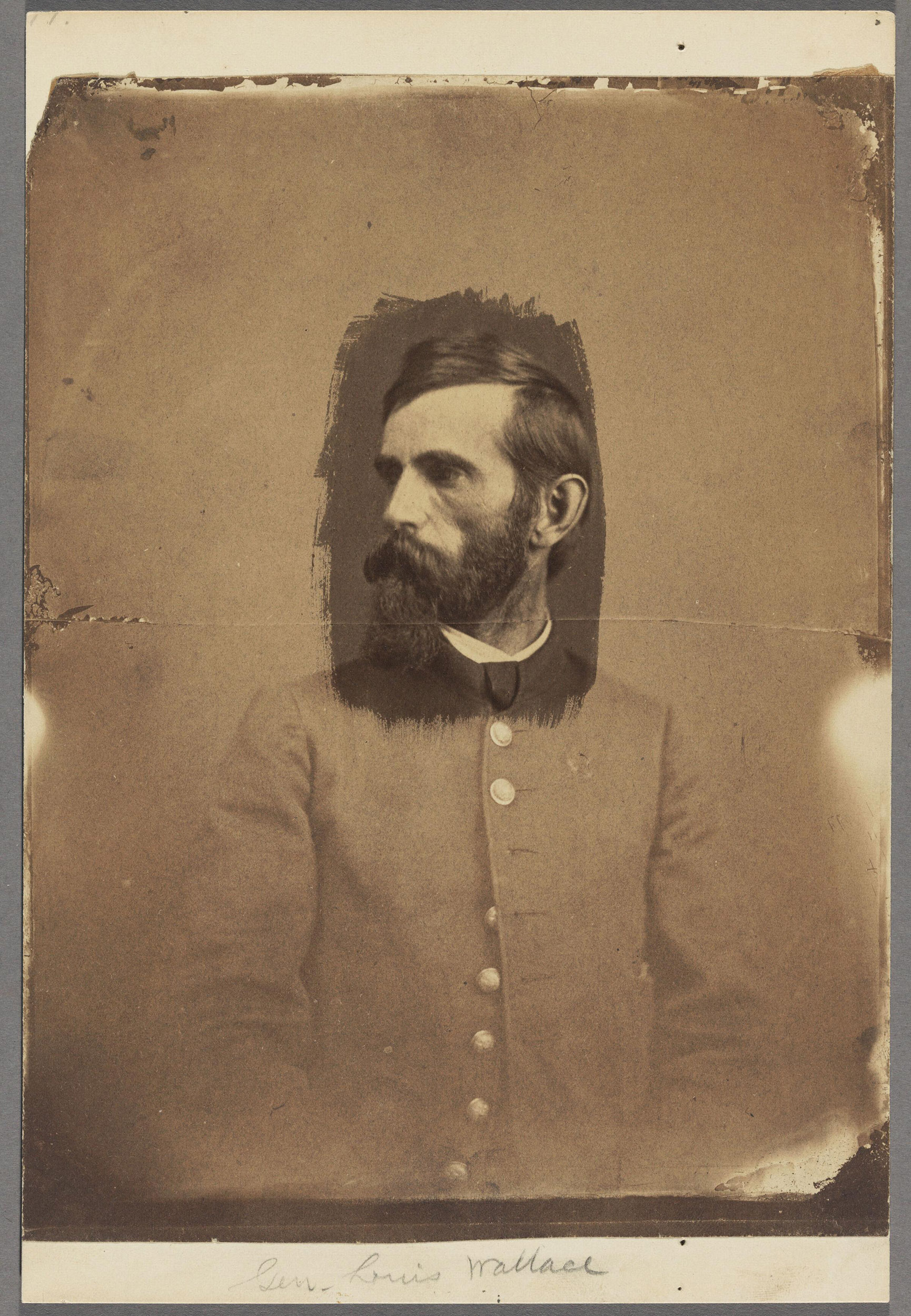

A portrait in the collection of “Ben-Hur” author Lew Wallace inexplicably has coating only on the subject’s face. Bulat said conservators have studied the coating and know its chemical makeup — gum arabic — and how to preserve it, but the reasoning behind coating only the face remains a mystery.

Some printmakers had a heavier touch than others as evidenced by the portraits of Lew Wallace and Charlotte Augusta Southwick Waddell.

Lew portrait courtesy of Harvard University, Fine Arts Library

In other cases, the printmaker was heavy-handed, and the photos have suffered for it over time.

Hand-applied media was a common addition to many prints, Maloney explained, to better represent colorful reality, and “runs the gamut from subtle artistic additions to quite garish.” Many photographers came from artistic backgrounds and could skillfully apply this media, which likely looked better when it was first added. Some hand-colored prints might even be mistaken for a drawing or painting at first glance.

A portrait of New York socialite Charlotte Augusta Southwick Waddell was hand-colored in the 1850s, perhaps to look more like a painting, conservators speculate.

Unfortunately, alterations like these can speed up deterioration of photographs since the added media ages differently. “Aging of salt prints with media applied, especially colored media, does not happen gracefully,” Bulat said.

In the case of Waddell’s portrait, at some point the coating became sticky due to humidity and attached to paper placed on top of the print. Conservators removed the paper remnants, a rare case of them taking action with a print due to a distracting unintended addition. Typically, when media or image material is lost, they will not attempt to replace it.

“We’re looking to keep our hand as invisible as possible,” Maloney said. “We want to make sure the print can safely make it into the hands of a researcher, but we don’t want to mediate their experience with the print. We let its whole history show.”

If you’re wondering if any of the old photos in your attic are salt prints, conservators offer a few clues: Salt prints tend to have a warmer tone and softer appearance and a rougher surface than albumen prints.

Photomontage, the Photoshop of the 1800s

Harvard’s salt print collection makes one thing clear — photographers in the 19th century were nothing if not creative.

Even today, with Photoshop and infinite “takes,” it can still be difficult to get a satisfactory group picture. Hundreds of years ago, the only editing option for photographers was to literally cut and paste.

Enter photomontage, a technique used to refine a group portrait taken around 1865 at a banquet held by railway developer and member of Parliament Sir Morton Peto on a visit to New York. The banquet had 250 guests, including generals, judges, and governors of multiple states, according to The New York Times. Only a select group made it into the photo.

“It was very difficult in that era to put so many people in one room to photograph,” Bulat said. “Often, not everyone was able to be physically present at the same time, and also group portraiture was difficult to make technically.”

As a result, photomontage and the similar technique of photocollage were common approaches for group portraiture.

The maker of this photomontage — likely famed mid-1800s photographer Mathew Brady, Bulat said, based on clues from the studio backdrop — probably took multiple photos of different sub-groups at Peto’s party. Then, Bulat explained, he covered parts of a negative image with opaque media, reprinted another negative on top of the first one, and processed them to look as though the whole group had posed at once.

“When you look closer, which you can do in HOLLIS images, you see many of the figures were planted here,” Bulat said.

The technique was far from perfect, she added. “They all look very artificial as a group, because they’re all looking in different directions and not at the camera.”

But photomontage and photocollage, which denotes cut-and-paste after processing rather than before, do show the ingenuity of photographers at that time.

A salt print photocollage of Peto’s group, Bulat pointed out, provides its own surprise — at certain angles, a faint sheen in the shape of a person is visible here and there on the image, where a print was cut and pasted into a new spot.

The “ghosts” showing the technique linger, for those who appreciate the medium enough to look.

For more information about Harvard’s Salt Print Initiative, visit the project website.