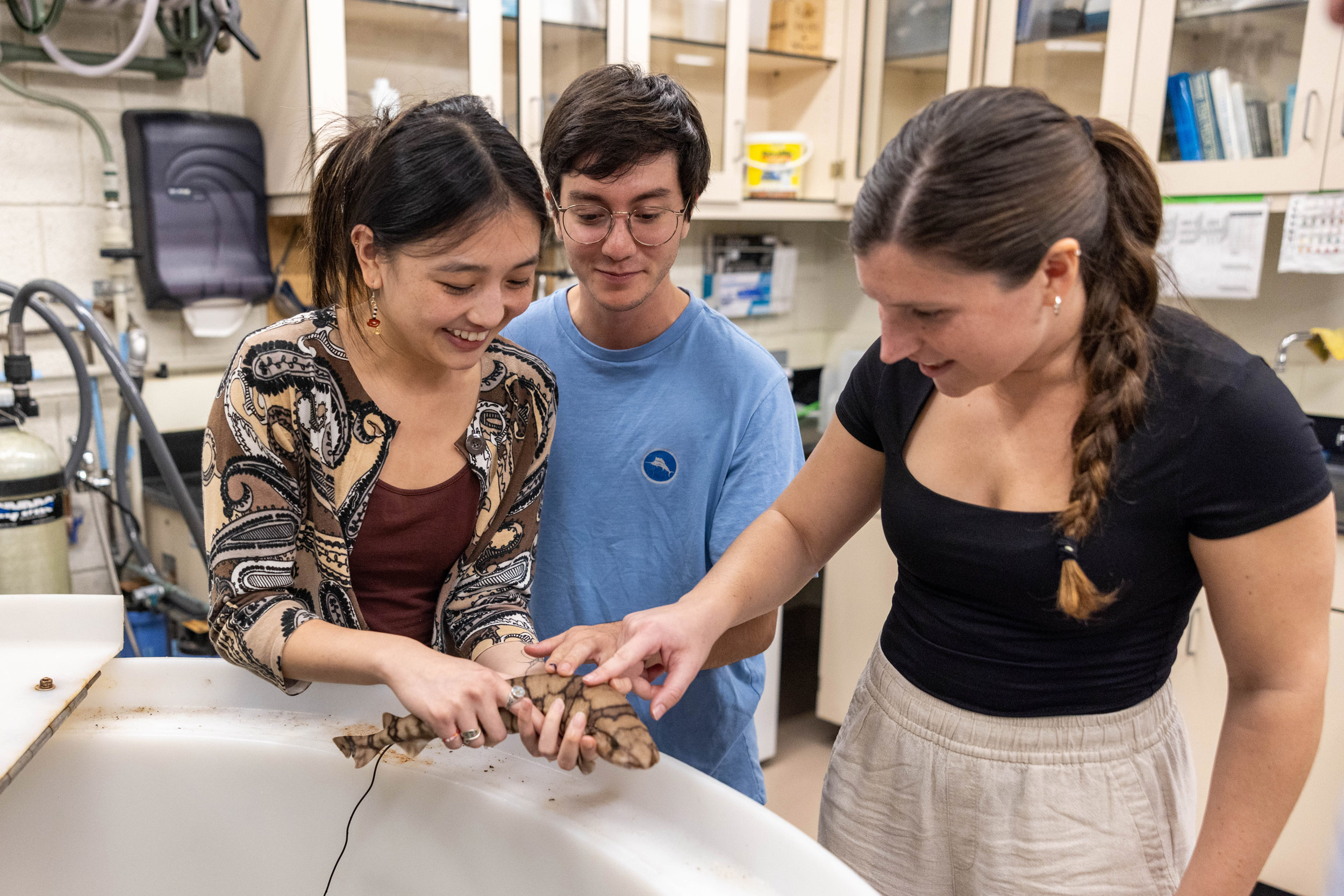

Dakota Law (from left) holds a chain catshark for fellow student researchers Nick Wallis Mauro and Gianna Mitchell.

Photos by Scott Eisen

Science no longer intimidates her. Neither do sharks.

Summer research program breaks down barriers for undergrads with disabilities

Dakota Law cradled a small shark as two fellow student researchers leaned in to touch it. Before this summer, Law had never worked in a lab or held a shark. Now she’s done both, thanks to an undergraduate research program geared to students with disabilities.

The rising senior in engineering sciences at Smith College is one of three students studying sharks for eight weeks this summer through the Research Experience for Undergraduates program Accessible Sharks, funded by the National Science Foundation. She worked in the lab of Harvard’s George Lauder. Scientists from Yale University and the University of Florida also took part.

Law, who has an invisible disability, talked about what the experience has meant for her. “I have been very hesitant and, honestly, kind of nervous about both going into the industry or continuing my journey through academia and how my disability might hinder my experience.”

None of that hesitation was evident in late July when Law’s peers in the program visited her in Lauder’s lab, and she showed off that chain catshark — and its denticles. The flat V-shaped shark scales, also known as “skin teeth,” have an enamel coating, dentin layer, pulp cavity, and blood vessels. They are of particular interest to researchers, Lauder included, because they help sharks swim more efficiently by reducing the drag around their bodies.

George Lauder studies hydrodynamics of shark skin.

Law has spent much of the summer probing how denticles influence the flow of water over a swimming shark. She learned how to use different kinds of technology to analyze skin samples and collect data on movement.

“I think lots of us, especially these days, are trying to diversify access to science and the scientific experience,” said Lauder, Henry Bryant Bigelow Professor of Ichthyology and Harvard College Professor in the Department of Organismic and Evolutionary Biology. “That has many dimensions to it. It has dimensions of race, dimensions of economic accessibility, emotional accessibility, mental health accessibility. We’re all trying to diversify science for the future, and this is just a part of that.”

University of Florida rising senior Nick Wallis-Mauro worked with Elizabeth Sibert at Yale University as part of the program. His focus was microfossils. Sibert, who is now at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, said that the goal of the research experience was to ground it in the science, not in disability.

“All of us are here for science,” she said. “As a scientist with a disability, I have felt very much alone and really appreciated any opportunities that I had to get to meet other people who also happen to be scientists and happen to be disabled in different ways.”

“I just really like sharks,” said Wallis-Mauro. “I saw this program and was like, ‘That’s crazy! Shark program for disabilities? That’s me!’”

This is the second year of the National Science Foundation grant for Lauder, Sibert, and Gareth Fraser of University of Florida to study sharks, but is the first year of the REU program. Researchers have discussed a plan to request additional funds to double the number of students next year. They also hope to inspire professors and researchers in other fields to lead similar opportunities for students with disabilities.

“It’s not hard to do … faculty just need to focus their efforts,” Lauder said.