Images courtesy of Harvard Art Museums

American stories in watercolor

Exhibition goes beyond idyllic landscapes to cramped apartment, 19th-century wardrobe malfunction, cancer-defying self-portraits

It’s early in the morning at Harvard Art Museums and Joachim Homann is pacing through the watercolor exhibition that he co-curated. The museum is not yet open and his voice echoes in the hushed gallery as he selects a handful of pieces to highlight from the exhibition of roughly 100 works representing some 50 American artists. The idea is that he’s going to informally chat about a few of the paintings, to provide readers with some context. He’s having a hard time deciding which ones.

Watercolorists on view range from the well-known, such as Winslow Homer, to the historically underrepresented — self-taught freedman Bill Traylor painted his featured portrait of a plowman and mule on the back of a cigarette advertisement. There are Edward Hopper’s tributes to a less touristy side of Cape Cod; John Singer Sargent’s take on a shoulder strap that so scandalized Paris, it drove him to London; Richard Foster Yarde’s vibrant remembrance of a Roxbury apartment, which he set askew to convey the psychological tension within; and in the exhibition’s earliest entry, precise renderings of daisies by Fidelia Bridges, the first American woman to earn her living through watercolor painting.

Once the difficult choices were made, we recorded Homann, the Maida and George Abrams Curator of Drawings, musing on these and several other works from the show. Listen to the audio clips below.

Curator Joachim Homann in the gallery.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

“American Watercolors, 1880-1990: Into the Light” is on view in the University Galleries on Level 3 through Aug. 13.

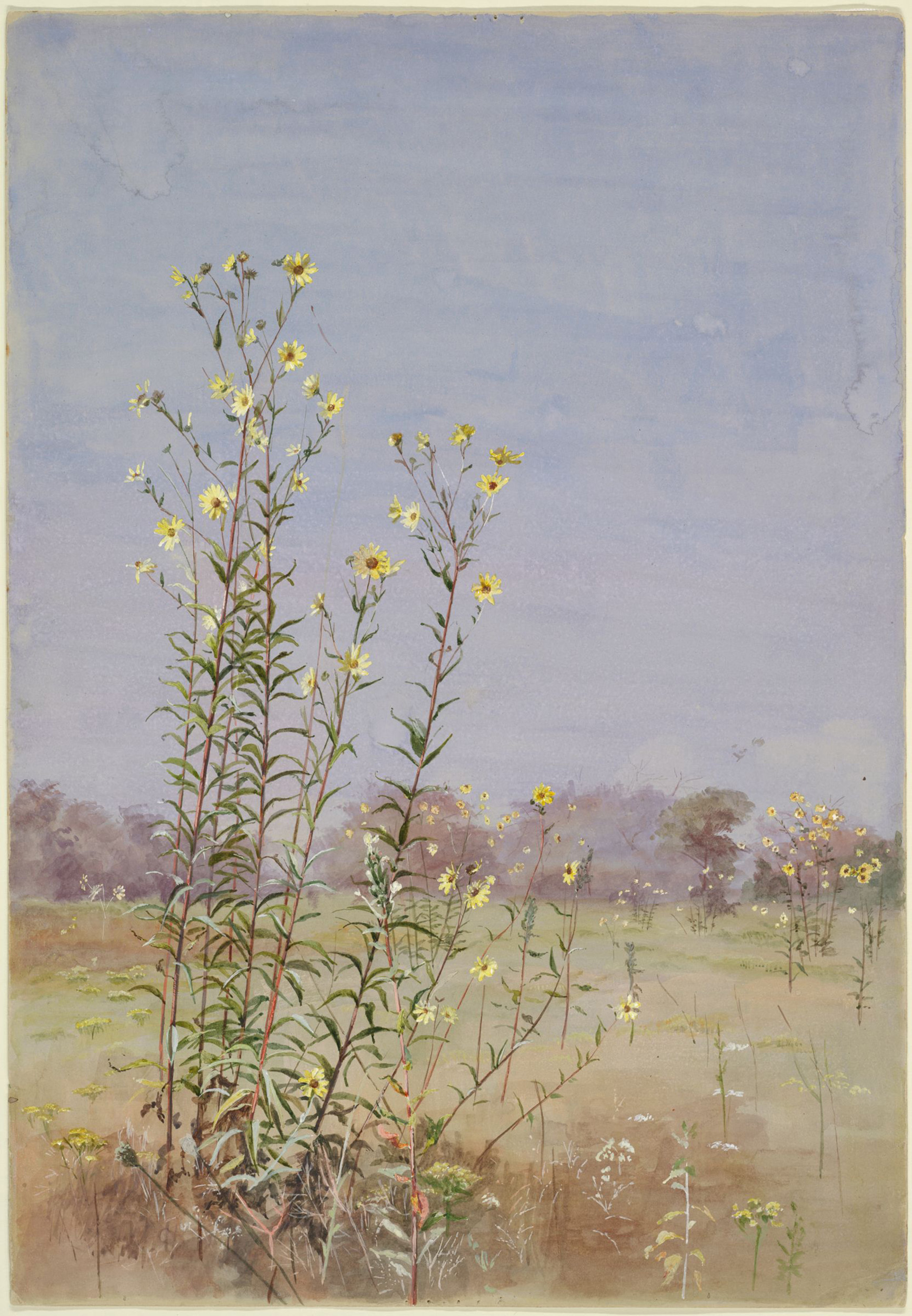

Daisies in a Meadow (1870-79)

Fidelia Bridges

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: Fidelia Bridges is the first work in the show that people are going to see. And her beautiful little flowers that are stretching into the sunlight are an homage for us to the many women who practiced watercolor already in the 19th century. Many of them were self-trained or trained at home by tutors. And Fidelia Bridges was one of the first women to have a professional education at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts and earned a living with watercolor. We are so pleased to have this work to remind people that watercolor was practiced by many women throughout the 19th century. And artists like Winslow Homer learned from women. The botanical arts were central to artistic pursuits of watercolor for a very long time.

Schooner at Sunset (1880)

Winslow Homer

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: Winslow Homer had a breakthrough moment in 1880 when he rented a little home on an island in the Gloucester Harbor and he experimented with watercolor like no American artist before. What you see here is a use of color that is very bold. The contrasts of the sunset on the harbor are very, very strong with almost an entirely black background set against the sunset and dark clouds hovering. What I find so special is Homer’s use of paper. He’s brushing on the paint without filling every single spot so the sparkle, the shimmer of the water surface is really beautifully visible. When this work was first exhibited in New York in a prestigious exhibition in 1881, it created a scandal because people did not know what Homer was trying to do. And he back-pedaled a little bit. This was one of his most radical works. But it freed him from anecdotal content in his work and he realized at this moment that he was going to be an artist who was going to make a difference with his watercolors in the canon of art history.

Madame Gautreau (Madame X) (c. 1883)

John Singer Sargent

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: Looking at the portrait of Madame X, who was Madame Gautreau, a professional beauty in Paris of American birth, married to a banker, is a lot of fun. This is only one watercolor out of the preparatory work that Sargent did for a big oil painting in the Metropolitan Museum of Art today that Madame Gautreau and Sargent planned out for the salon, the big contemporary art exhibition in Paris. And they tried to be a little bit more daring than Parisian audiences were accustomed to. So the strap on her shoulder with this very deeply décolleté dress is very loosely painted and a little ambiguous and it almost seems like it would come off at any time. When Sargent translated this from his watercolor into the oil painting and exhibited the work, people got really scandalized and he was forced to repaint the strap to more securely fasten the dress on the body of the sitter. [Laughter] And the responses were so controversial that Sargent decided to move to London and leave Paris behind.

Mink Pond (1891)

Winslow Homer

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: The work “Mink Pond” is a real visitor favorite, and I’m coming back to it again and again. Homer is changing the perspective here. He’s almost looking from a frog-eye perspective on his favorite fishing pond in the Adirondacks, which he showed many times in the more human perspective. But here you have a close-up view of the frog and the fish as if they’re having a conversation. It’s very deeply darkened and the most glowing part of it is this beautiful water lily in full bloom that’s also reflected on the pond water. It gives you a sense of the artistic inspiration that might be behind this. At the time — this was from 1891 — Bostonians, New Englanders were very enthusiastic about Japanese art. And Homer, often considered the most American of all artists, was not averse to applying a Japanese inspired aesthetic to a work like this that he created practically in the wilderness in the Adirondacks while he was on a fishing vacation.

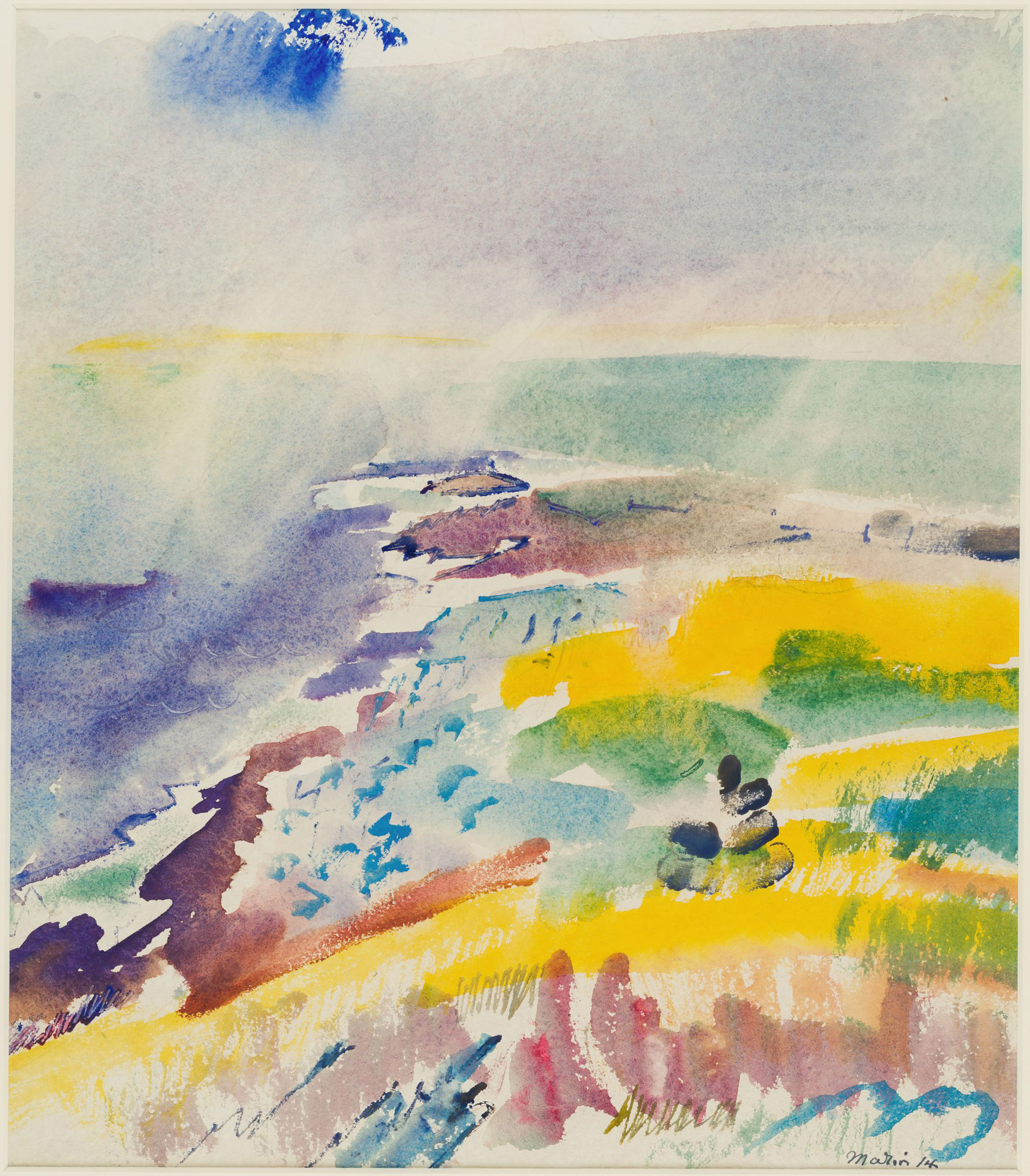

Seascape (1914)

John Marin

© Estate of John Marin/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: John Marin’s “Seascape” from 1914 signals the arrival of modernism in the watercolor world. This was Marin’s first trip to the coast of Maine — midcoast Maine and the Georgetown area. And he was completely inspired by the arrival of modern art and the famous Armory Show in New York in the previous summer and showed off his work with colors, with spontaneous paint application. He was able to experiment with application techniques like no one else. So you see his fingerprints forming a little tree in the foreground in dark colors. Some of the stripes of the deep rose set in the front of the picture might also be created with his fingerprints. He wipes off in the distance the kind of misty appearance. Some wet colors he sponges off and that creates mist. And then when you look carefully into the water, you see that he took the back of his brush and scraped off, drew with the back of the brush, some waves into the water color as well. So it’s a very experimental, very direct work that is incredibly freshly preserved. It’s so bright in the galleries, it makes everybody happy who sees it. And it hadn’t been even photographed in color before we photographed it for the catalog. So we are happy to showcase it and and celebrate it in a way it hasn’t been celebrated ever since it came to the museum.

Cold Storage Plant (1933)

Edward Hopper

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: We have a fantastic wall of four Edward Hopper works, watercolors that he created in the early 1930s when he was summering in Truro on Cape Cod. One of the most unexpected works from this group is the “Cold Storage Plant” from 1933 that shows a plant that was built right on the water on the bayside with the view of Provincetown in the background jutting almost into the water from the dunes. It’s a very dramatic, very modern-looking structure with red brick that’s gleaming in the sun and Homer is just unbelievably skillful in rendering the bright summer light that shines on the structure illuminating and shading in different ways every single aspect of it. I’m pointing this one out because it’s the only of the structures represented in these Edward Hopper watercolors that doesn’t stand any longer. It was taken down when it was obsolete in the 1960s, I believe, so there’s nothing there at this point. But Edward Hopper’s interest as a modernist to see a different side of this tourist destination, to show the modern angle, I think is really noteworthy. And it’s a glorious work that I feel is one of the strongest works in the exhibition. So I picked this one rather than the lighthouse for this selection because it’s so unexpected and maybe a different side, that we don’t usually see of the working waterfront, of the Cape.

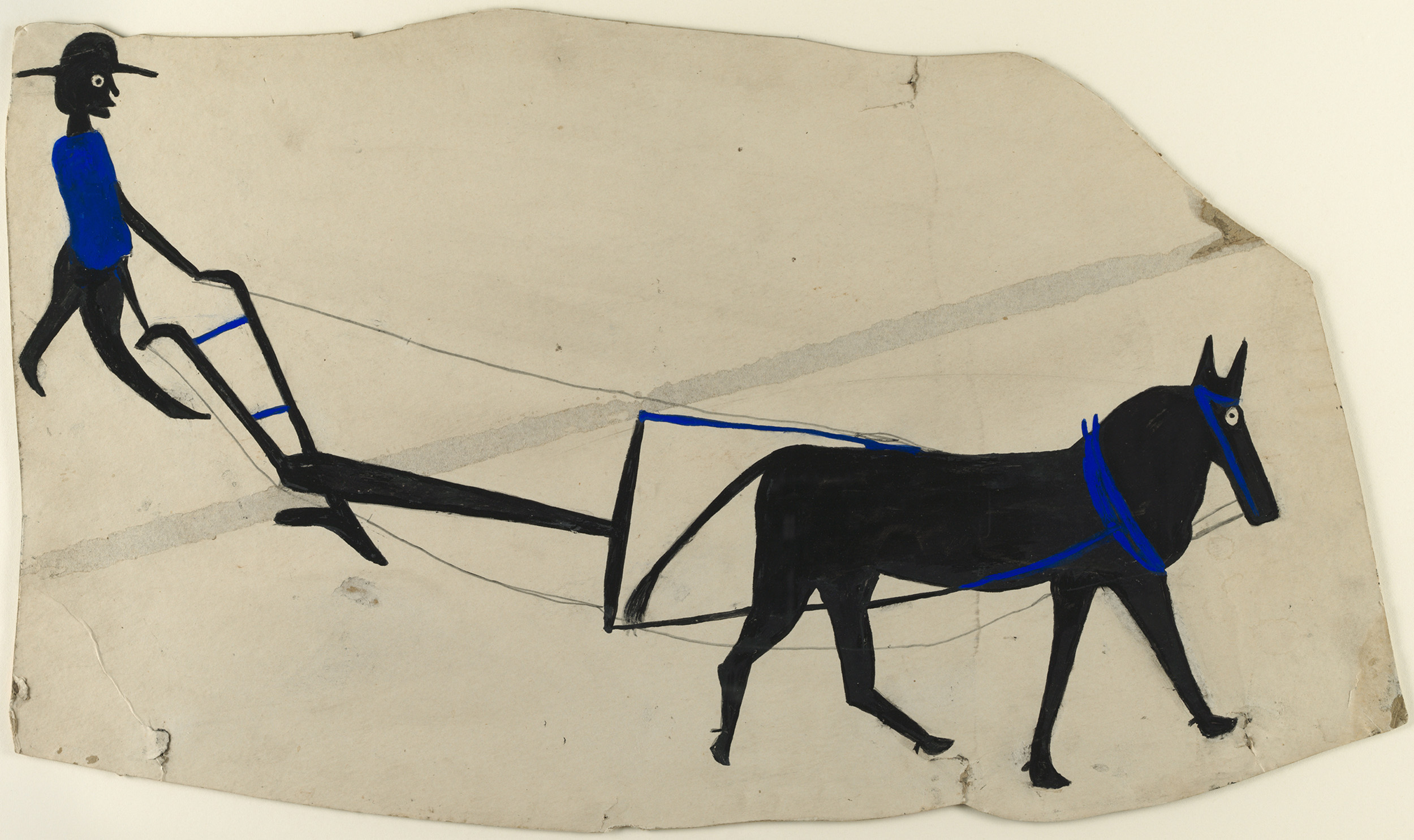

Mule and Plow (c. 1939-42)

Bill Traylor

© Bill Traylor Family Trust

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: It’s a gorgeous work by the artist Bill Traylor that I find especially striking in terms of its graphic power. It really bounces off the wall and holds its own in this exhibition that’s studded with masterpieces. Bill Traylor is the only artist in this show of American art who was born into slavery. He lived a long life in Alabama, and as a freedman living in Montgomery he was known to collect scraps of paper and cardboard like this one, which is the flip-side of an advertisement with a full-color image of a basketball player advertising whatever it is. And Bill Traylor in a really ingenious way used the irregular shape of the paper to envision the scene of a man leading a plow through the field drawn by this horse. And what’s fascinating about it is that the figure and the horse are both fit into this sheet of cardboard in a way that really enhances the dynamic. It gives you a sense of space, of realism that’s unexpected because his figures are so reduced, the formal language is very reduced. One detail that I want to point out is the legs of the farmer, which are so irregular — one is much longer than the other, and that’s not what you would do, if you draw a stick figure, you try to get the legs the same length because you know that the human body has approximately the same length of legs. But here he wants to show how the guy steps into this space and how the dynamic is, what this is all about. It’s a really wonderful solution that shows an artist who was very creative, very thoughtful, and knew how to look at things and use the materials and techniques he had at his command at the best effect.

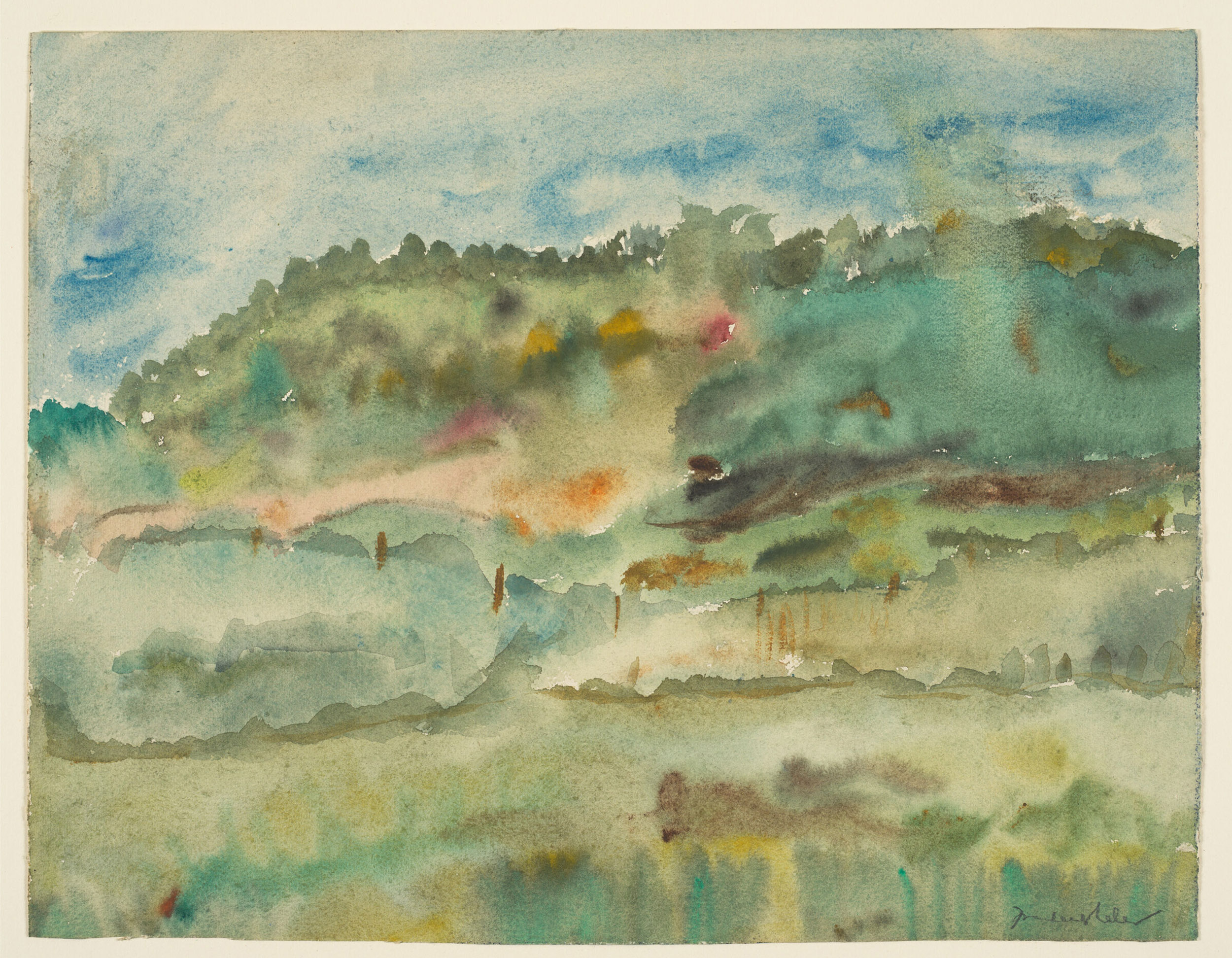

Landscape (c. 1951)

Helen Frankenthaler

© Helen Frankenthaler / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: Helen Frankenthaler graduated from Bennington College where she took art classes. And a few years later came back to campus in Vermont with her boyfriend Clement Greenberg, who was one of the great art critics of the period. Both of them painted in the studio for much of their summer vacation but each day they would take the watercolor box out into the country and would paint the scenery in watercolors. It’s kind of hilarious to think of that because Helen Frankenthaler is known for enormous paintings on unprimed canvas that she, rather than painting it in traditional ways, stains with various colors. That staining technique that she developed in the winter of 1951 to 1952 actually has its roots to a certain degree in the watercolor practice from the summer, in the watercolors that she did like this one here on view. The use of wet-on-wet technique, of the application of wet watercolor on a wetted sheet of paper that creates these wonderful kind of enigmatic, abstract, floating forms and color sensations on the paper — this is something that when she was back in the winter in her studio, she recreated with the stain canvases. So it’s an indication of how watercolor is a process that challenges artists to come up with new ideas and to think outside of the box, how it then translates for many artists in this exhibition into breakthrough moments in their work in oil on canvas as well.

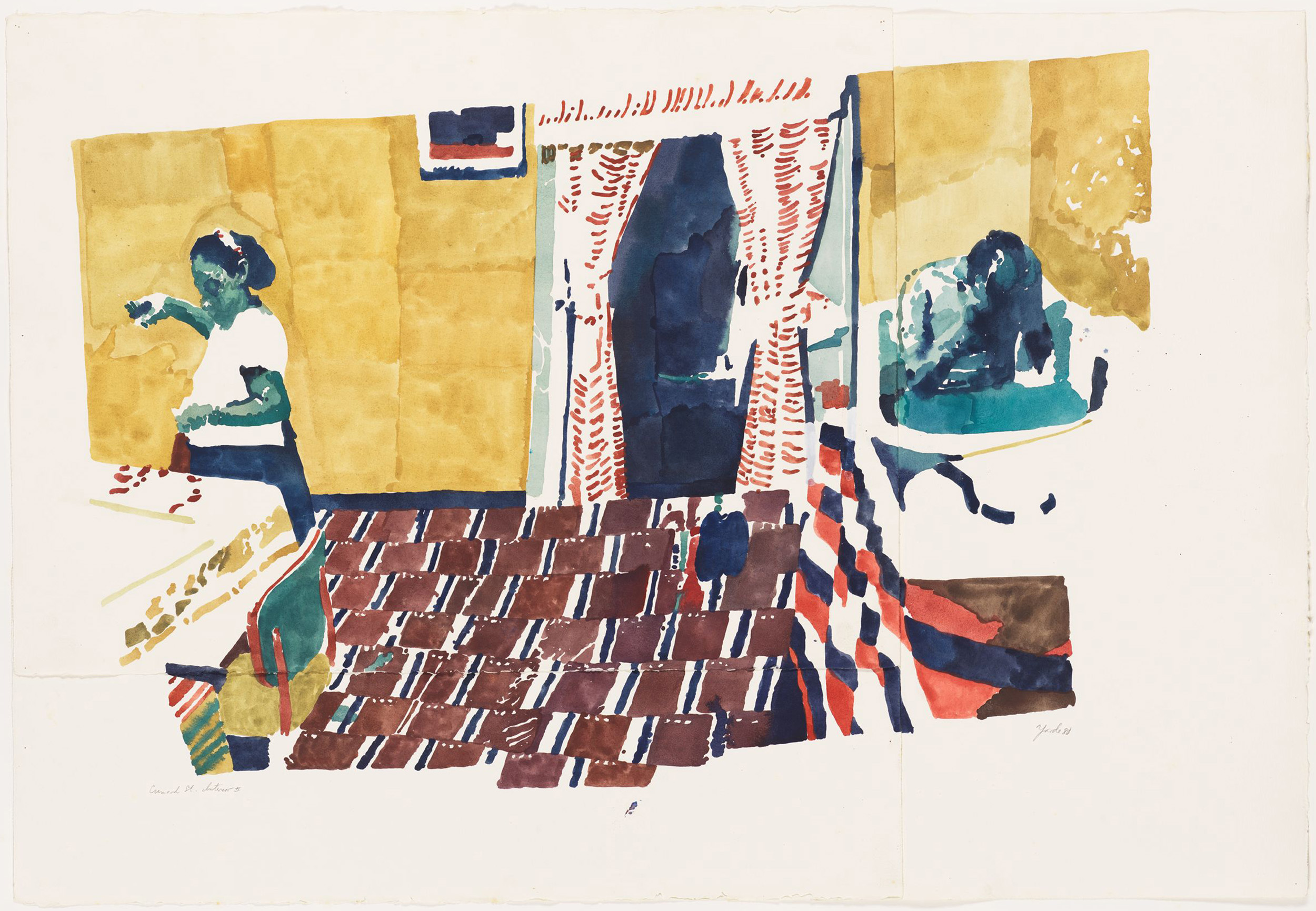

Cunard Street, Interior II (1980)

Richard Foster Yarde

© Estate of Richard Foster Yarde

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: I’m so pleased to be able to present a more diverse, more interesting, and richer history of American art with this exhibition. We are thrilled about additions to the collection and one of the most spectacular is this watercolor by Richard Yarde, a Massachusetts artist. He had grown up in Roxbury and around 1980 he dedicated a series of large watercolors interestingly painted on several papers that are only loosely attached to each other. He painted the series to remember his childhood. And you see here a kitchen / bathroom, a very inconvenient setup for the two people who are shown here living side by side in really cramped rooms. But the way he is patterning the surface, the way he’s using the reserve, the white paper ground, to make the whole room sparkle and make it beautiful and engaging. Also the way that he suggests a psychologically intense situation with the figures that he places very carefully on two different sheets but in the same room. It’s just really, really wonderful and shows the full creativity of an artist who is counted among the greatest watercolorists of the later part of the 20th century.

Self-Portrait, B.C. Series (1990)

Hannah Wilke

© Marsie, Emanuelle, Damon, and Andrew Scharlatt, Hannah Wilke Collection & Archive, Los Angeles. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

transcript

Transcript:

Joachim Homann: Hannah Wilke was a feminist artist who made her own body, her own experience, her own place in the world the theme of her art. She’s working without reserve and it’s really raw and very engaging. Her late work, the series of self-portraits represented here with three beautiful examples was created in response to her mother being diagnosed with leukemia as far I understand. Hannah Wilke created on a daily basis as a routine of survival and self-affirmation, of demonstration of her physical prowess in the face of death, she created a series of these large watercolors on the floor of her studio with big bold brush strokes that are colorful and wonderful to look at. But the face that they seem to represent is as if it’s reflected in wavy water, it seems to fizzle away as you look at it. Tragically, as she was creating the series, she was herself diagnosed with cancer and then passed away afterwards. What I find important here is that watercolor in the context of this exhibition takes on a different dimension. It’s as much about mental health, it’s about the physical workout, it’s about a daily routine as it is about the subject or image that’s represented. And that’s a good reminder of the important place that watercolor as a medium plays for many of the artists in the exhibition, as a practice and not as a product.