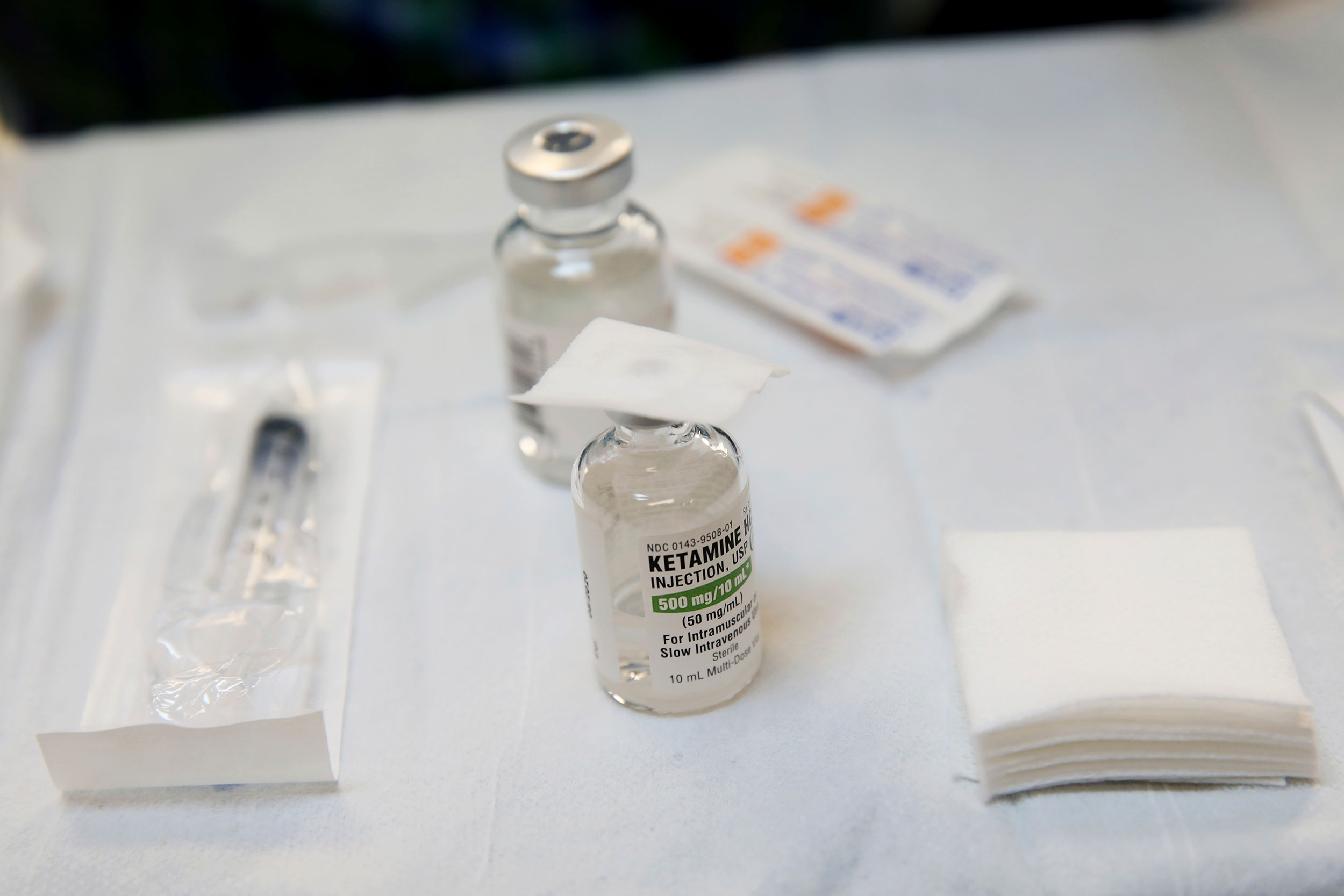

Ketamine was approved by the FDA as a sedative/analgesic and general anesthetic.

Yalonda M. James/San Francisco Chronicle via AP

Ketamine found effective in treating severe depression

Had no major side effects compared to electroconvulsive therapy, considered the ‘gold standard’ treatment

Study tracks effects to three key brain regions

In a clinical trial of 403 patients, Massachusetts General Brigham investigators found that 55 percent of those who received ketamine treatment experienced a sustained improvement in depressive symptoms without major side effects.

The new MGB-led study compared subanesthetic intravenous ketamine to electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for the treatment of non-psychotic, treatment-resistant depression. The results are published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“ECT has been the gold standard for treating severe depression for over 80 years,” said Amit Anand, director of Psychiatry Translational Clinical Trials at Mass General Brigham and professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School. “But it is also a controversial treatment because it can cause memory loss, requires anesthesia, and is associated with social stigma. This is the largest study comparing ketamine and ECT treatments for depression that has ever been done, and the only one that also measured impacts to memory.”

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is a leading cause of disability worldwide and is estimated to affect 21 million adults in the U.S. ECT involves inducing a seizure via electrical stimulation of the brain. Ketamine is a low-cost dissociative drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a sedative/analgesic and general anesthetic. Previous studies have suggested that low doses of the drug may have rapid antidepressant effects for people with MDD.

The trial was conducted from March 2017 to September 2022 at five sites with 403 patients randomized one-to-one to receive either ECT three times per week or ketamine twice per week for three weeks. Patients were followed for a period of six months after treatment and responded to a depressive symptom self-assessment questionnaire, which also included memory tests and questions about quality of life.

[gz_pull_quote attribution=”— Amit Anand, professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School”]“This is the largest study comparing ketamine and ECT treatments for depression that has ever been done, and the only one that also measured impacts to memory.”[/gz_pull_quote]

The researchers found that 55 percent of those receiving ketamine and 41 percent of those receiving ECT had at least a 50 percent improvement in their self-reported depressive symptoms and an improvement in their self-reported quality of life that lasted throughout the six-month monitoring period. ECT treatment was associated with memory loss and musculoskeletal adverse effects. Ketamine treatment was not associated with side effects other than an experience of transient dissociation at the time of treatment.

The current study is the largest-to-date real-world comparative effectiveness trial of ECT vs. ketamine. The trial took a patient-centered approach, with three types of independent depression ratings (patient, rater, and clinician) captured and no active solicitation of participants.

“For the ever-growing number of patients who do not respond to conventional psychiatric treatments and need a higher level of care, ECT continues to be the most effective treatment in treatment-resistant depression,” said psychiatrist Murat Altinay, lead of the trial site at Cleveland Clinic. “This study shows us that intravenous ketamine was non-inferior to ECT for treatment of nonpsychotic treatment resistant depression and could be considered as a suitable alternative treatment for the condition.”

The authors note that their findings are based on self-reported outcomes and that the trial’s open-label design could have influenced response rates. But its patient-centeredness and real-world design may also be a strength, allowing the findings to be more easily translated into clinical practice.

Anand’s team is now working on a follow-up study comparing ECT and ketamine treatments for patients with acute suicidal depression to see if the same promising impact is found in that population.

“People with treatment-resistant depression suffer a great deal, so it is exciting that studies like this are adding new options for them,” said Anand. “With this real-world trial, the results are immediately transferable to the clinical setting.”

This study was funded by the Patient Centered Outcome Research Institute (TRD-1511-33648) and sponsored by the Cleveland Clinic.