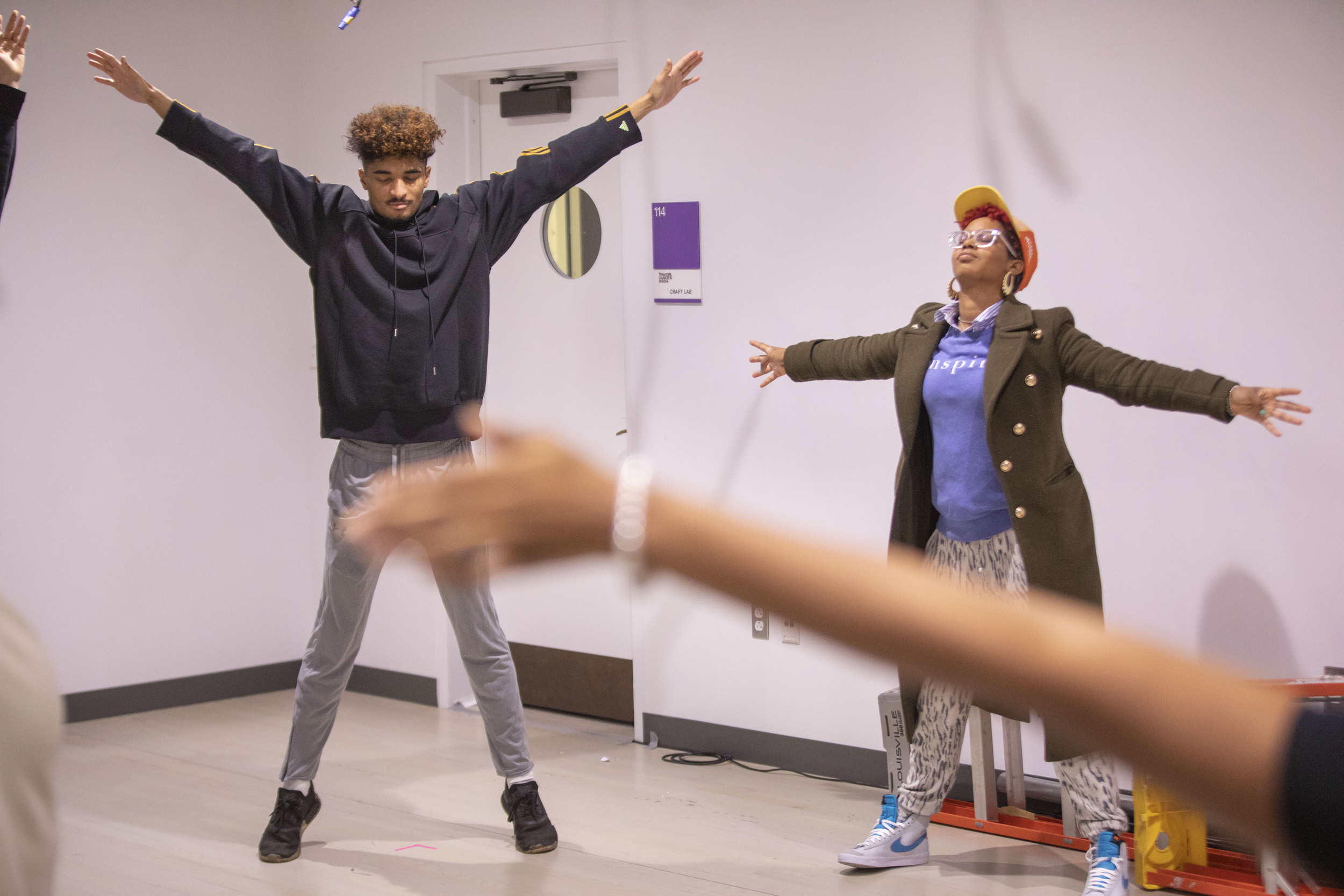

“Rise up and stretch out as wide as you can and take up space,” Shamell Bell (right) told her students, including Max Booker (left). “This is your worth. This is your value. You are allowed to take space.”

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Transforming breath to activism

Theater, Dance & Media course, rooting in issues surrounding death of Eric Garner, blends ritual, meditation, reading, ‘radical dialogue’

Students gathered in a circle and began to stretch as they readied themselves for a rowing exercise led by a classmate. “Rise up and stretch out as wide as you can and take up space,” she said. “This is your worth. This is your value. You are allowed to take space.” Students took deep, intentional breaths throughout, pushing their arms out straight and pulling them back.

Rituals, as well as meditation or “grounding experiences,” are a key component of Shamell Bell’s new course, “Ritual of Breath is the Rite to Resist Social Impact,” in Theater, Dance & Media. The lecturer on somatic performance and contemporary global performance in TDM follows those in-class rituals with “radical dialogue” on issues of race/ethnicity, gender, cultural appropriation, and the act of healing from traumatic experiences.

“Dr. Bell’s class felt like the perfect opportunity to explore the intersection of ritual, resistance, and justice that drives so much of my own work at Harvard and beyond,” said Auds H. Jenkins, M.Div. ’24. “In a world where so many of us are combating systemic oppression, loneliness, and state-sanctioned violence, ritual has the power to connect and ground us on our journey to liberation.”

Bell, who took on feminist writer bell hooks’ “engaged pedagogy” approach, collaborated with students on speakers, readings, and videos. The class — a mix of undergraduate, graduate, and Divinity School students — were asked to complete prompts from Liberation Journal, a publication focused on “manifesting freedom and liberation,” and to read hooks’ “Teaching to Transgress” and Robin D.G. Kelley’s “Freedom Dreams.”

Colombian American artist Yazmany Arboleda and Mary Lou Aleskie, executive director of the Hopkins Center for the Arts at Dartmouth, were among the speakers who met with the class throughout the semester.

“Ritual of Breath” is based on an eponymous opera written by poet Vievee Francis, responding to the death of Eric Garner, a 43-year-old Black man, during an arrest by New York City police. The hourlong performance examines the struggles faced by Garner’s daughter, Erica, who is thrust into the spotlight in the aftermath. His 2014 death — and final words, “I can’t breathe,” uttered as he was pinned to the ground by officers — moved millions to join a national protest movement against the mounting numbers of deaths of Black Americans at the hands of police.

“This work centers the life and murder of Eric Garner as a metaphor for how we can embrace healing, experience, and resistance through that breath and then ultimately transform that to activism,” Aleskie said.

Aleskie first approached Bell with the “Ritual of Breath” project when the dancer-choreographer was a single mom pursuing her doctorate at the University of California, Los Angeles. At the time, Bell was deeply involved in the Black Lives Matter movement and had begun dancing as an act of radical joy and a form of resistance.

She joined the initiative as social impact co-director, along with Garner’s mother, Gwen Carr. The two were tasked with devising pre-opera rituals aimed at inspiring action and conversations about anti-Black violence. While the opera itself “is an act of resistance,” Bell said that the rituals help to ensure that it “is more than just performative activism.”

“We were very much looking for a platform for how to put activism in the hands of artists, but also make sure that communities don’t stop with this and actually embrace agency,” Aleskie said.

Bell first taught “Ritual of Breath” at Dartmouth College. “Education is a practice of freedom,” Bell said, referring to hooks’ “Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. She noted that the course she teaches is all about healing.

Now the responsibility of developing rituals falls on her students, who will reimagine the exercises and activities that will accompany the opera when it premieres for the Boston-Cambridge community. As part of their finals, students are required to develop a vision for their communities.

“I want people to know that change is possible, and that the revolution is already here. As we make the decision to center love in our work, doors of possibility fling open,” said Jenkins, who is working with fellow Divinity School students to “build a multifaith, queer, BIPOC-led intentional living community.”

“We see experiments in living differently as a critical component of our spiritual education and our work to dismantle capitalism, racism, and all other forms of oppression that hinder our flourishing. The dream is big, but this class reminds me that the future is shaped by dreams like ours.”