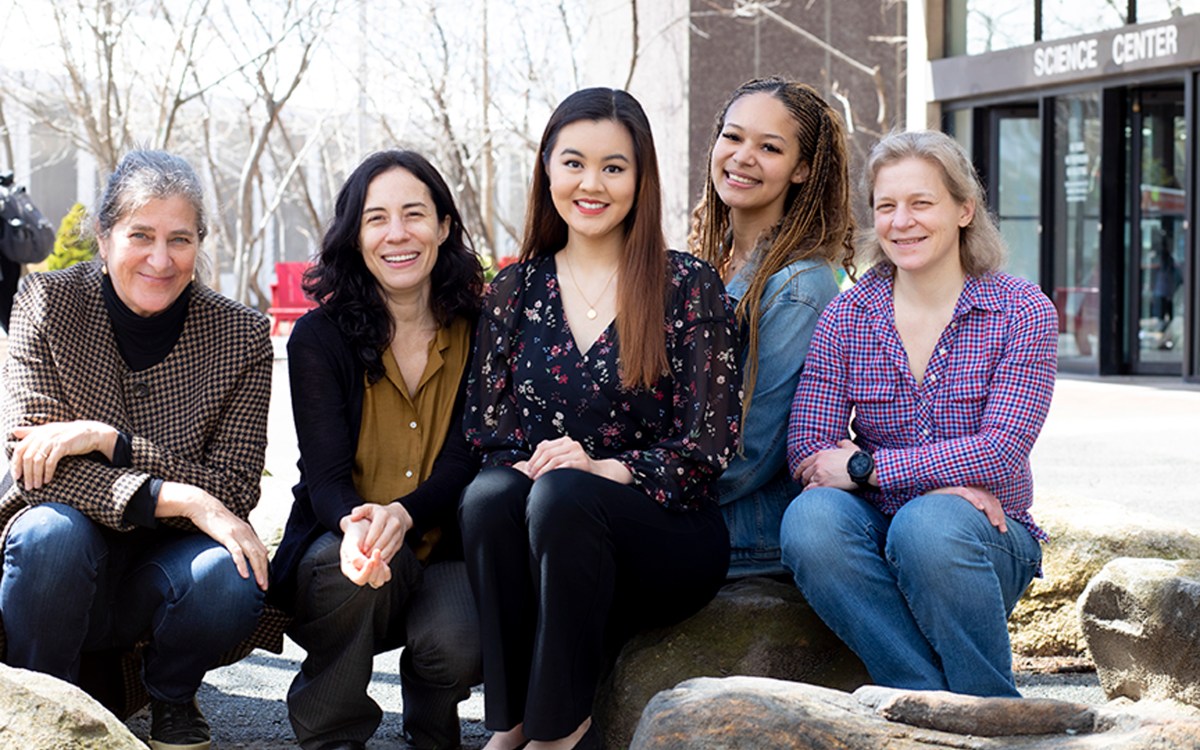

Alia Qatarneh (far right) runs the 2022 Boston 10K for Women with fellow members of the run crew TrailblazHers, Erin Wallace (from left), Angel Babbitt Harris, Abeo Powder, and Elaine Kordis.

Photo courtesy of PUMA/PUMA Running

Outrunning the past

Inspired by ‘village’ of fellow athletes, shaped by Harvard mentors, Alia Qatarneh helps BAA move forward

Growing up in East Boston, Alia Qatarneh would watch the Boston Marathon on TV, racing with her younger sister around the coffee table to see if they could keep pace with the elite runners. But she still felt a long way from the start line.

No longer.

On Monday, the Harvard researcher will compete in the 127th Boston Marathon, hosted by the Boston Athletic Association. When she mentions running as a representative of her all-female crew, TrailblazHers Run Co, her face lights up.

“It’s so, for me, incredibly powerful,” said Qatarneh, the daughter of a Jordanian immigrant father and a first-generation Italian-American mother. “In my wildest dreams, I never thought that I would be running this race that I’ve wanted to run for years, on behalf of a village.”

Qatarneh has a lot on her plate, intentionally. She does research. She teaches. She raps. She leads. She’s about to run her first marathon, but even more important, she’s a voice for change within a historically exclusive community. Women weren’t allowed to officially run the Boston Marathon until 1972. And for people of color, many barriers — cost, time, access — still exist. The BAA is hoping to change that, and Qatarneh is part of the movement.

“The BAA has a long history,” said Adrienne Benton, the first woman of color to serve on the BAA’s Board of Governors. “Some of it has been inclusive, and some of it has not been inclusive.”

Qatarneh competes in the Boston 10K for Women.

Photo courtesy of PUMA/PUMA Running

Boston, dating to 1897, is the world’s oldest annual marathon. That history comes with a lot of baggage. Benton, a member of Black Girls RUN!, has been heartened by the BAA’s commitment to help fight bias that has plagued the city for decades, but she’s also quick to point out that real progress will require sustained collaboration with neglected groups.

“We can move mountains if we allow each other space and listen to each other,” she said.

Suzanne Jones Walmsley, a Harvard alumna and the BAA’s director of youth and community engagement, cited the Boston Running Collaborative, founded in 2021, as a step forward. In a first, the collaborative has allotted multiple race bibs to athletes from underrepresented communities in the city. This year, nine inaugural runners will compete as part of the initiative. Qatarneh is one of them.

“When you have a race like the marathon that’s been successful, and it’s exciting, you don’t necessarily look at who’s there and — more importantly — who’s not there,” said Jones Walmsley ’91, who was inducted into Harvard’s Track and Field Hall of Fame in 2006. “You’d like to think it’s an equal system … but when you don’t dig down into what some of the systems are that prevent people from getting to a point where they can equally access [the race], you’re doing yourself a disservice.”

To enter Boston, a runner must qualify or compete through the BAA’s charity program, which requires raising a minimum of $5,000. Next up: expensive gear, supplemental nutrition, and hours (and hours) of training, any of which can be a barrier to entry. “Especially for people that live in the city — and this race happens in their hometown every year — how do we provide access to opportunity for them to be able to participate?” Jones Walmsley said.

On long training runs, Qatarneh has had plenty of time to ponder the same question.

“What does it mean to trailblaze?” she said. “To me, it means to change things with intention.” In other words, her goal is to help inspire a movement of empowered people who push back against the status quo and reject old ways of thinking. “I’m challenging the running sector by disrupting the narrative around what it means to be and look like a runner,” she said. “And I’m disrupting within the Harvard community by challenging what it means to be a scientist.”

Qatarneh, who received a master’s degree in biotechnology from the Extension School in 2020, directs a science education program housed in the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. As a female scientist of color, and in a world where men still hold 65 percent of STEM occupations and where 70 percent of doctoral science degree recipients are white, she understands acutely the need for creating an environment that helps students thrive. She credits Harvard faculty and researchers, specifically the late biologist Rob Lue, with guiding her in her own professional journey.

“I’ve been very fortunate to be part of a team that has been incredibly uplifting and supportive,” she said. Lue, she added, “definitely fostered an environment where people felt supported and able to be their authentic selves.”

“What does it mean to trailblaze? To me, it means to change things with intention.”

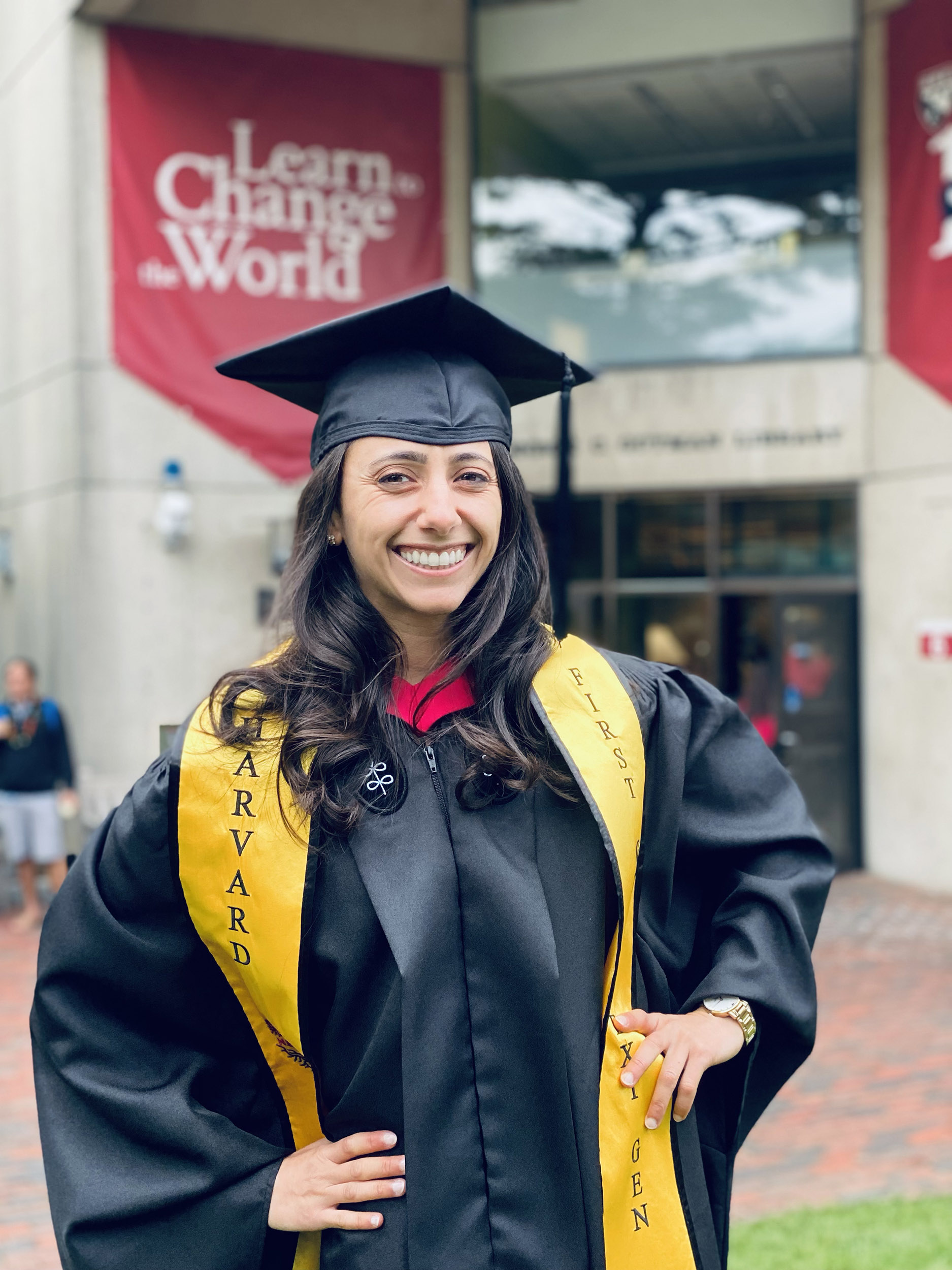

Qatarneh outside Gutman Library after receiving her Ed.M. degree in 2022.

Photo by Daniela Hernandez

Another key Harvard experience was earning a master’s of education, which included mentorship from lecturer Christina Villarreal, who teaches a course called “Toward Healing Centered Engagement in Classrooms, Schools, and Communities.” For a student like Qatarneh, encountering a faculty member who reminds them of their own upbringing or experiences, whether that’s because of how they look, talk, or think, can be transformative, Villarreal said.

“How I choose to show up as my full authentic self has consequences, but also tremendous rewards. [Qatarneh] saw that and responded strongly to it. I’ve had the privilege of witnessing her run with it. And then come back and talk about how she was bringing the practices into her running group.”

The co-founders of TrailblazHers — Liz Rock, Abeo Powder, and Frances Ramirez — have worked hard to ensure that women of color feel safe in a sport that hasn’t always welcomed them. Qatarneh has been central to the effort, Powder said: “The way she creates space and makes others feel seen and heard, that’s been very paramount to the success and the growth of TrailblazHers and the Greater Boston running community.”

That growth — and the determination of athletes like Powder, Qatarneh, and their fellow TrailblazHers — is equally important to the BAA’s Jones Walmsley.

“These are the individuals that are really making the difference and doing the work,” she said. “And as an organization, we are grateful to be able to come alongside them. My hope is that their vision for what the Boston running community can look like becomes everyone’s shared vision, and that everybody can see themselves as a part of the sport.”

Now it’s time to run. In the days leading up the race, Qatarneh has allowed herself to feel the breadth and depth of emotions associated with Marathon Monday. The memory she returns to most is from one of her first long training sessions. When a few other runners asked if she wanted to join them, she declined, wanting to move at her own pace. It was her introduction to the notorious hills of the course, and it was difficult.

“And that was the first and last time that I did that,” she said. “I’m going to carry that with me. It’s not just about the building of community, but it’s actually leaning on that community when I need it.”