Illustration by Trina Dalziel/Ikon Images

Young people are hurting, and their parents are feeling it

Experts react to Pew findings with advice for families, including ideas for at-home interventions

The father needed answers.

He’d recently completed a six-week Mass. General program designed to help parents whose children were struggling with ADHD. He had read the material — and re-read it. He’d tried to connect with his daughter. But nothing was working. She was frustrated. He was frustrated. Their relationship felt broken.

I don’t know what to do, he told his doctor. Can you please help?

The physician, Dana Allswede, a psychologist in the hospital’s Child Outpatient Psychiatric Department, remembers the email as one of many describing similar sentiments. Every week she hears from overwhelmed parents. For some, it’s about toddler tantrums. For parents of older children, the urgent question is whether their teenager is displaying normal adolescent behavior or something more serious.

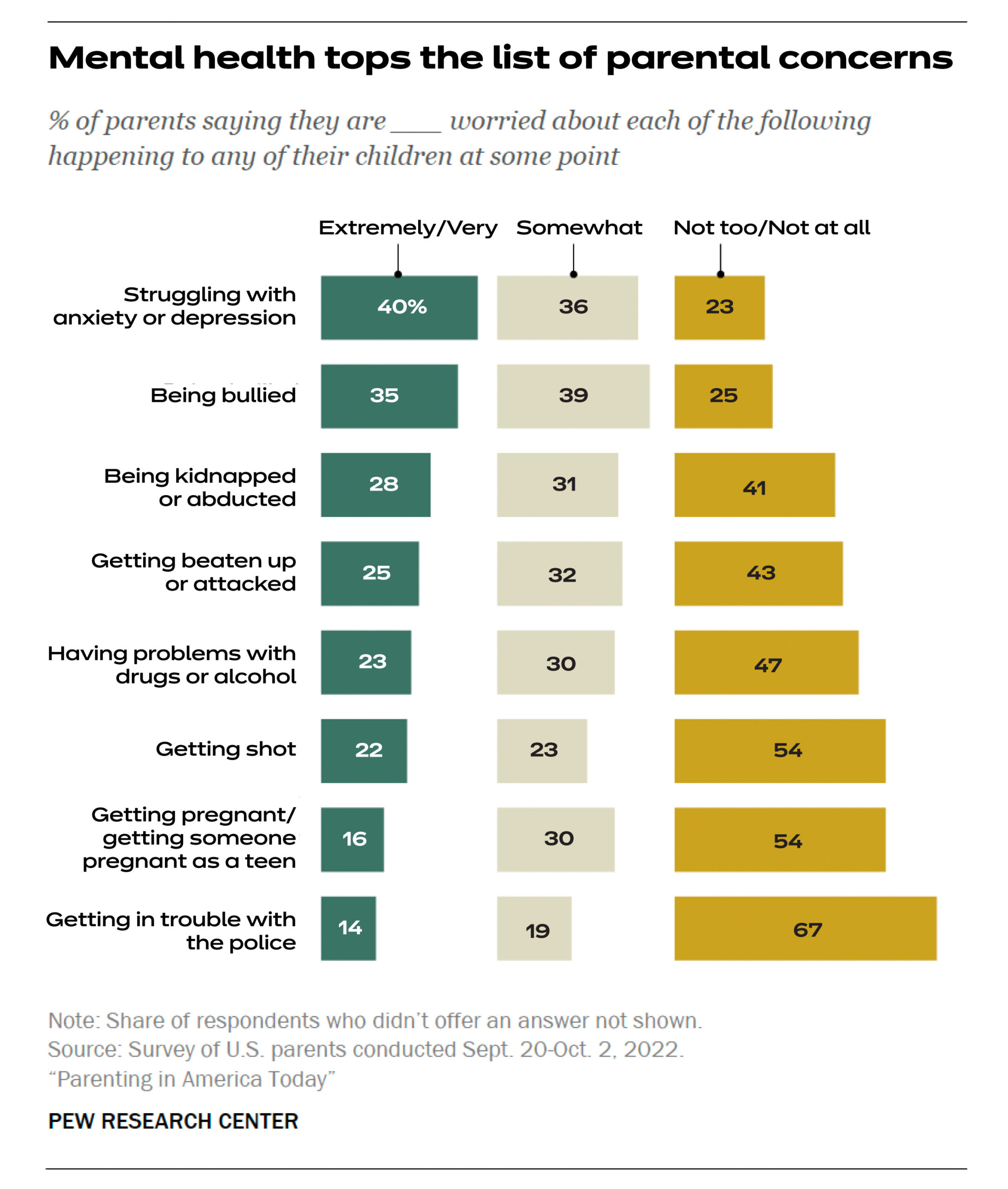

These accounts follow national trends. Pew Research Center’s Parenting in America Today survey, released in January, found that mental health issues are a top concern for parents, with 40 percent saying they are extremely or very worried that their children are struggling with anxiety or depression, and 36 percent feeling somewhat worried. In 2015, only 54 percent of parents reported worrying at all.

The Pew survey follows 2021 findings from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in which more than a third of high school students reported poor mental health during the pandemic, with almost half experiencing persistent levels of sadness and hopelessness.

“There are clear data to show that youth have been disproportionately affected in terms of the mental health impact relative to some of the other age groups,” said Archana Basu, a research scientist in epidemiology at the Harvard Chan School and a clinical psychologist at MGH. Even before COVID, the numbers were moving in the wrong direction, with the National Library of Medicine and the CDC reporting increases in depressive symptoms and suicide-related behavior.

John Weisz, who runs Harvard’s Lab for Youth Mental Health, notes that as mental health issues for children have risen, there are fewer providers to care for them. “Access was reduced partly because many clinicians left the workforce or reduced working hours because of the pandemic’s impact on their families,” he said, “and also because many clinical services stopped or sharply reduced in-person services.”

In other words, many families are forced to wait months before seeing a clinician, leaving them to navigate on their own. The most important thing parents can do? Take care of themselves.

Psychologists Dana Allswede (left) and Archana Basu discuss the connection between parents’ well-being and their children’s.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

“Parents investing in their own mental health is actually one of the most effective things for children,” Basu said. “Because the more regulated they are, the more emotional availability they have and the more they can support their children.” The more parents can model what it’s like to regulate their own emotions, the more children can learn to do this for themselves. This connection is beneficial for all children, from newborns to high schoolers.

Allswede has also seen the benefit of parents investing in themselves. One project she works on brings parents together virtually to share information and talk about the challenges they face, without their children present.

“[It’s about] connecting them with other parents who are going through the same thing so that they know they’re not alone, and they can lean on one another,” she said. “It’s felt more isolating to be a parent in the past few years … everyone has been through a lot.”

When parents have the mental and emotional capacity to support their children at home, the effect is powerful, Basu says. Physical health and mental health are usually intertwined, so focusing on being active together, healthy eating, and ensuring that everyone is getting enough sleep has major implications for a family’s well-being. Parents can also encourage healthy peer interactions and social activities, or even introduce cognitive behavioral tools like mindfulness and relaxation. Parental monitoring — setting clear expectations, discussing social decisions, and responding appropriately to a child’s behavior — is not only an expression of concern but guards against risky behaviors such as substance use and unsafe sex. Each of these small activities has the potential to make a huge difference.

“Anything that helps to moderate and mitigate the impact of a severe or traumatic stressor could be thought about as a buffer or protective factor,” Basu said.

Another option is remote care. In a meta-analysis led by the graduate student Katherine Venturo-Conerly, the Lab for Youth Mental Health found that remote delivery of mental health care yielded positive effects similar to those of in-person care. Additionally, the pandemic prompted the lab to accelerate development of “brief digital interventions” that children can complete on their own. These resources can be made available for use at home, helping to fill clinical gaps.

“There is much that parents can do on their own to help their children develop resilience and coping skills,” Weisz said. “It makes a positive difference when parents understand what the treatment is that their child is receiving, what the goals are, and how skills learned with a therapist can be implemented, practiced, encouraged, and praised in real life outside of therapy sessions.”

On a policy level, Basu emphasizes that any measure that supports parents ultimately supports children. Passing legislation such as paid parental leave or revisiting which interventions merit insurance coverage would represent important steps in making resources more accessible and giving parents what they need to succeed.

Allswede said that in her support groups, she has seen parents become emotional and tearful when they share how meaningful it is to feel understood. Normalizing these challenges can help them open up about their experiences, which helps other families navigate their own situations. All of this gives parents the bandwidth they need to support the positive mental health of their children.

“We use the metaphor often of putting on your own oxygen mask before putting on your child’s oxygen mask,” she said. “I hear from families all the time who have been managing really challenging situations on their own for so long … [they] desperately need this support and reach out. And I’m glad they do.”

If you or someone you know needs access to mental health services at Harvard, visit the University’s Counseling and Mental Health Service or call 617-495-2042. For more information about resources at Harvard and the We’re All Human wellbeing initiative, visit: harvard.edu/wellbeing.