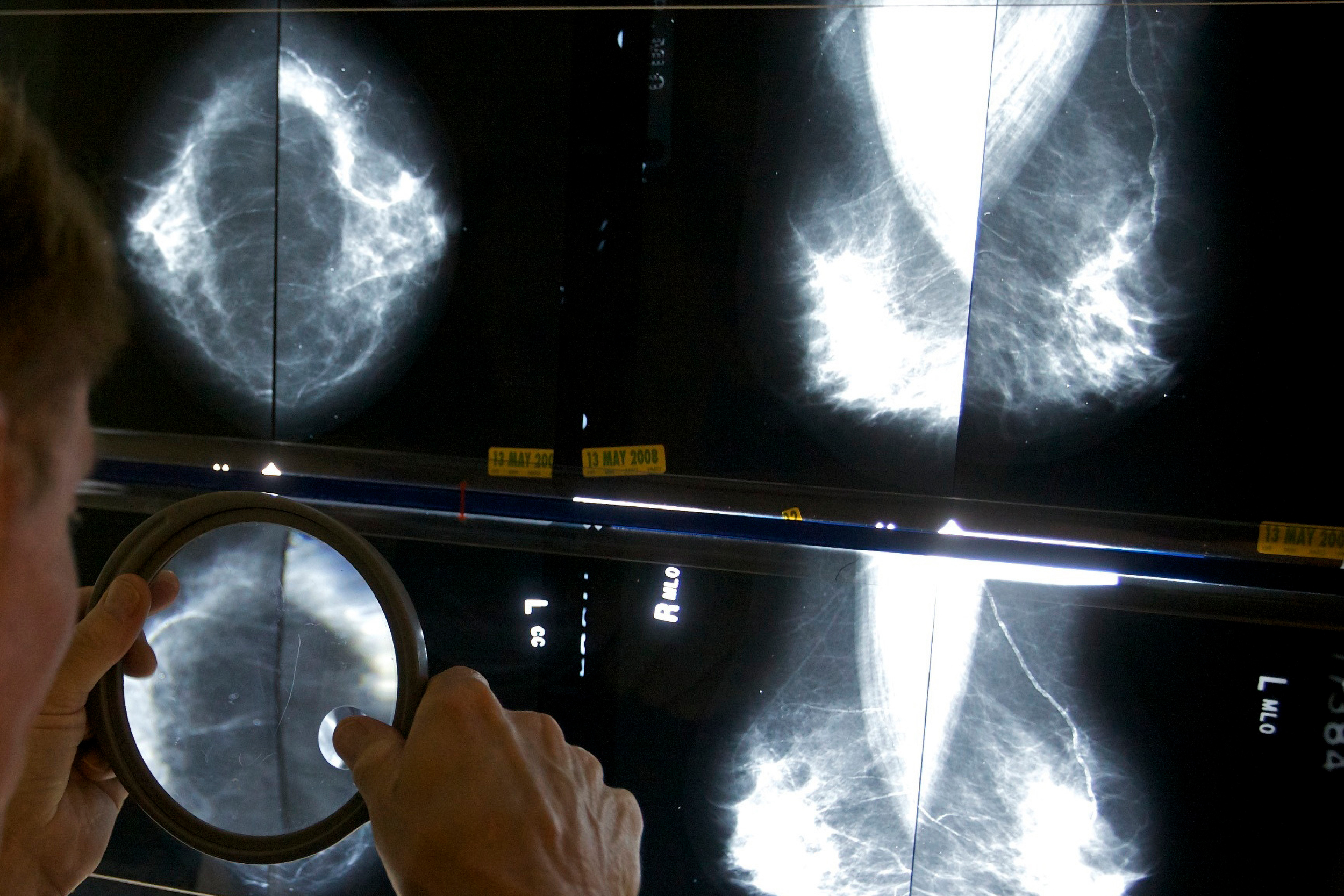

A radiologist checks mammograms for breast cancer.

AP file photo

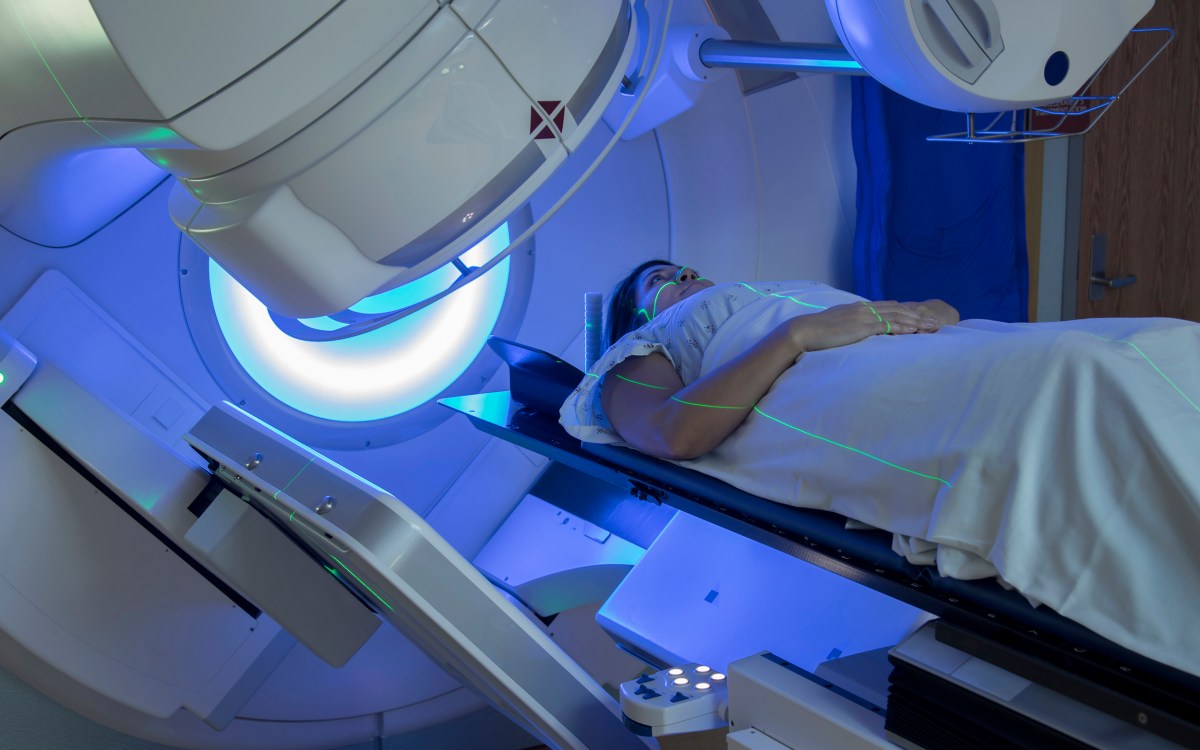

New FDA rules may help with prevention, detection of breast cancer

But, diagnostic radiologist says, one of most important aspects of ensuring patients are notified of tissue density is what it adds to doctor-patient dialogue

The Food and Drug Administration recently announced that doctors will now be required to disclose a patient’s breast density at mammogram clinics. This was already required in 38 states, but the new regulations will even the playing field when it comes to providing patients with information that could affect their health outcomes. The Gazette spoke with Connie Lehman, a nationally renowned diagnostic radiologist in the Mass General Cancer Center and a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, about how this may affect the prevention and detection of breast cancer. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q&A

Connie Lehman

GAZETTE: For those who’ve never heard this term before, what is breast density?

LEHMAN: What breast density is not is how your breast tissue feels; neither a woman nor her doctor could tell density from a breast exam. Rather it’s the density on the X-ray or mammogram. When you have a mammogram, there are different types of tissue in your breasts that show up differently. The really dense, harder to penetrate tissue shows up as white. And the really easy to penetrate tissue, fatty breast tissue, shows up dark. Cancers show up as white on the mammogram, and that is why they can be hidden or “masked” by the white dense breast tissue.

GAZETTE: Does breast density change throughout your lifetime?

LEHMAN: For most women it does change, but the changes aren’t as dramatic as women think. Many people have heard that young women have dense breast tissue, and older women have fatty breast tissue. But really what we see is women have a set amount of dense breast tissue in their life, and when they start to go through menopause that breast tissue density can start to decrease. But it’s not nearly as dramatic as the difference we’ll see between two women. So you can have two 40-year-olds, one has totally fatty breast tissue, and the other has totally dense breast tissue. We can see two 80-year-olds, one has completely dense breast tissue and the other has completely fatty breast tissue.

“Dense breast tissue can mask or cover cancer,” the Medical School professor said. “It can also raise the risk of developing breast cancer.”

Photo courtesy of Connie Lehman

GAZETTE: Most states already had notification requirements. So will the FDA decision make much of a difference?

LEHMAN: It really does. First, all 50 states now have this law that they need to follow, and second, it provides consistency across all 50 states. Before, we had a lot of variation in how individual states were addressing density notification, and now we’re going to have a lot more consistency. I think that’s a good thing.

GAZETTE: Why is it important for women to know about their breast density?

LEHMAN: There are really two aspects in the guidelines. The first is to make sure that patients understand that dense breast tissue can mask or cover cancer. And the second is that it can also raise the risk of developing breast cancer.

GAZETTE: In what ways do both of those issues need to be addressed?

LEHMAN: It creates two different care pathways. Because we know it’s harder to find breast cancer, patients can talk to their doctor and say, “Should I have other imaging tests besides the mammogram? Do you think an ultrasound or MRI might help?” We know that ultrasounds and MRIs can find cancers in dense breast tissue that can be missed on a mammogram. So that’s one follow-up that can happen.

The second part, about density raising the breast cancer risk, can help women talk to their doctor and say, “What are things I can do to reduce my risk? Or other ways that I can understand my risk besides just my dense breast tissue?” Honestly, I think the added risk of density has been way overplayed. And some women have a fear that because they have dense breast tissue, they have a very high risk of breast cancer. And that’s not true. The vast majority of them will never develop breast cancer. We’re doing a lot of work now in the field to address that so we can have more accurate, precise ways to give a woman her true sense of future breast cancer risk.

“It’s not a precise metric. … We really need to make sure that we’re providing the resources, education, and information needed so patients understand what this means.”

GAZETTE: Some doctors think that disclosing this information to their patients could actually be misleading. Why is that?

LEHMAN: I think there are two reasons why this can be misleading. One is we’re still unfortunately, in a place where the assessment of a woman’s density on her mammogram is a very subjective assessment by the radiologist. Radiologists really vary in how well they can assess a woman’s breast density. A woman might be told by one radiologist she has dense breast tissue, but the next year a different radiologist reads her mammogram and says she doesn’t have dense breast tissue. So it’s not a precise metric. The second part that I think doctors are raising concerns about is that it can raise unnecessary fears. We really need to make sure that we’re providing the resources, education, and information needed so patients understand what this means.

GAZETTE: Is there a risk in being too cautious? Are there consequences of over-screening or diagnosing?

LEHMAN: False positives are a significant concern. We absolutely don’t want to miss cancers; we don’t want any woman to be diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer. But at the same time, the more testing we do, the higher the risks are for false positives, women undergoing unnecessary exams, even in some cases, unnecessary surgeries. So we’re trying to find that balance.

GAZETTE: In some ways, it sounds like this regulation is really forcing a centering of trust between patients and doctors. Why do you think that’s important?

LEHMAN: I believe my patients deserve access to their information. I think of it as a dialogue; the information belongs to this woman, and then she can use that information to talk to her doctor. Density notification really started in February of 2004 with Nancy Cappello. She was diagnosed with late-stage breast cancer just six weeks after she had a normal mammogram report and her doctor commented, “I’m not surprised because you have dense breast tissue.” And she said, “What does that mean? And why have I never been told that?” She was the one who carried this through.

Unfortunately, she has passed away since she first started her work. This is a big celebration in her memory; she wanted patients to be informed in a way she was not, wanted doctors to give this information to their patients, and patients to ask their doctors about what they should do. She’s the force behind all of this. With information shared between patients and their doctors, that trust has to be there.

GAZETTE: For now, what would you recommend women do if they learn they have dense breasts?

LEHMAN: I don’t think they should be concerned. Forty to 50 percent of women in the U.S. have dense breasts. It isn’t a bad thing; it’s normal and natural. But it’s good information to have, in addition to family history or other factors that might increase their risk. They should absolutely talk to their health care provider and ask if they can help them understand their risk better. It’s an opportunity to have a conversation.