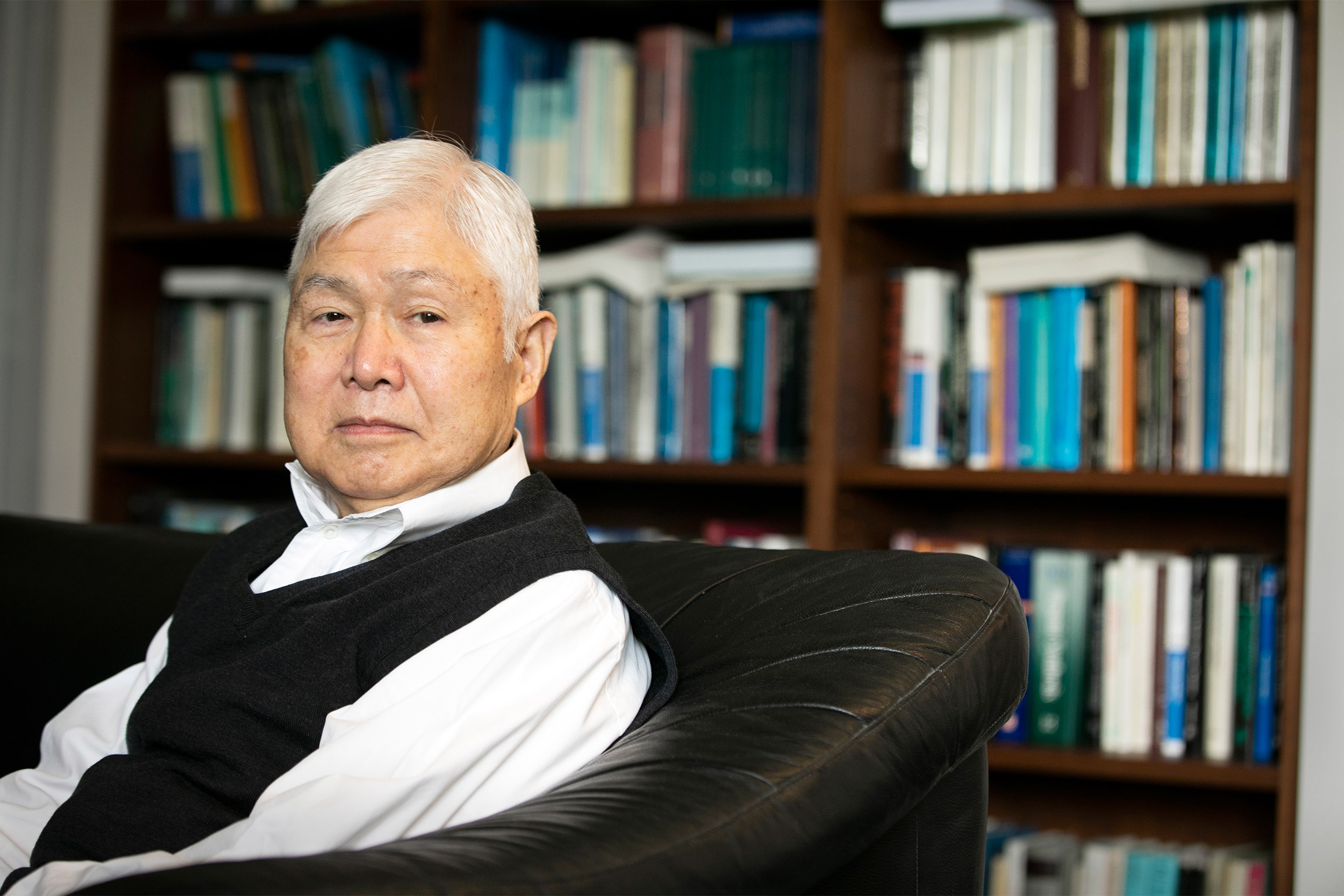

Yoshito Kishi’s work led to the creation of a drug that treats metastatic breast cancer and liposarcoma.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Towering figure in organic chemistry

Yoshito Kishi remembered for developing important anti-cancer agent and as devoted mentor

He was a towering figure in organic chemistry renowned for his syntheses of complex natural products and impact on the development of halichondrin, paving the way for the creation of powerful cancer therapies. But in addition Yoshito Kishi, who died earlier this month at the age of 86, will be warmly remembered by colleagues and students as a devoted mentor who was wise and generous with his advice on research and careers.

“Kishi was a primary force in the modern era of synthetic organic chemistry, having the type of transformative effect seen by R.B. Woodward and E.J. Corey in earlier eras,” said Stuart Schreiber, Morris Loeb Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, the department in which Kishi worked for nearly 50 years. “His pioneering work resulted in a new appreciation of the reach and power of this field.”

Recalling Kishi’s friendship and kindness, Schreiber added: “I knew Yoshi for more than 45 years, and I had the extraordinarily good fortune to receive his mentoring steadily and unrelentingly. He is still the voice in my head questioning the significance of new avenues of research and the fortitude of my efforts to travel down these avenues.”

Born in Nagoya, Japan, in 1937, Kishi received his B.S. and Ph.D. degrees from Nagoya University under the supervision of Professor Yoshimasa Hirata, who was acclaimed for his achievements in the chemistry of naturally occurring compounds. In 1963, Kishi married his wife, Tokiko. Three years later, he became an instructor at Nagoya before taking a leave to come to Harvard to study the synthesis of vitamin B12 as a postdoctoral fellow in the lab of Nobel Prize-winning Professor Robert B. Woodward. Woodward was renowned for his creative and cutting-edge work on complex natural product synthesis, marshalling a team of diligent and exacting chemists with rigorous planning and analyses.

“Kishi’s synthesis of palytoxin is considered to be one of the greatest achievements in the history of the field because of the complexity of the molecule.”

Eric Jacobsen, Sheldon Emery Professor of Chemistry

Woodward was impressed by Kishi’s “experimental skill” as a postdoc, noting in a lecture that all his operations were “conducted with every conceivable precaution in respect to purity of reagents, exclusion of oxygen and moisture, and with the greatest possible speed.”

Upon completing his fellowship, Kishi returned to Nagoya as an associate professor, but returned to Harvard as a visiting professor in 1972. He joined the faculty as professor of chemistry in 1974, and served as chair of the department from 1989-1992.

Kishi’s syntheses of natural products are characterized by their creative designs, astounding complexity, and practical application.

“Kishi’s synthesis of palytoxin is considered to be one of the greatest achievements in the history of the field because of the complexity of the molecule,” said Eric Jacobsen, Sheldon Emery Professor of Chemistry. “His ability to construct incredibly complex natural products in his lab was unparalleled, but he was also being really innovative and creative in terms of what he could achieve and learn from those syntheses.”

The Kishi Lab advanced methods of convergent synthesis, which enables complex molecules to be assembled from subunits rather than constructed linearly. One innovation that bears his name, the Nozaki-Hiyama-Kishi reaction, protected the highly reactive functional groups while they were being assembled. In 1992, Kishi achieved the first total synthesis of a halichondrin molecule (halichondrin B), and a simplified version of that molecule, eribulin, became a drug that treats metastatic breast cancer and liposarcoma.

“This extraordinary drug resulted from Kishi’s advances in organic synthesis, especially his catalytic diastereoselective chromium/nickel-mediated coupling reactions,” Schreiber said. “Eribulin is by far the most complex synthetic drug to impact human health, and its impact on taxol-resistant cancers is substantial.”

In addition to his vital research, Kishi mentored the robust network of scholars who studied in his lab, taking a keen interest in their careers and well-being. Jean-Christophe Harmange, a postdoctoral fellow from France in the lab from 1993 to 1994, recalls Kishi’s guidance as both cerebral and personal.

“I had a health issue that was going to cost me through the roof in America, but Kishi found funding for me to be treated.” Harmange said. “He was demanding when you were in the lab, but he was also an extraordinarily humble and nice man, caring about us as individuals and our families.”

Theodore Betley, the Erving Professor of Chemistry and chair of the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology, recalled Kishi’s kindness to his fellow faculty.

“Yoshi was incredibly generous with his time and welcoming to his colleagues in equal measure,” Betley said. “His kindness will not soon be forgotten.”

In addition to his wife, Kishi leaves two daughters, Hiromi and Satoko.