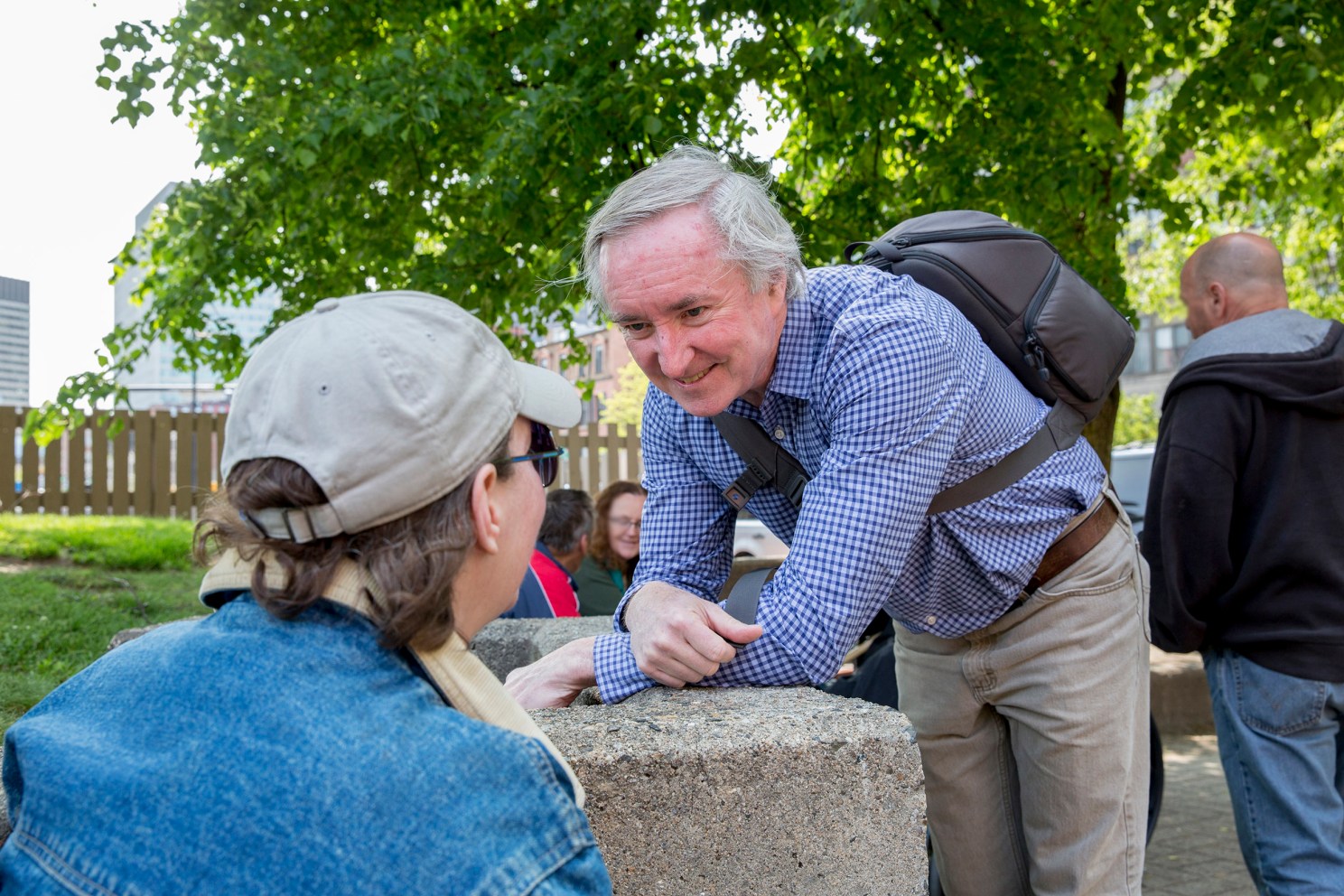

Jim O’Connell brings health care to the streets of Boston.

Harvard file photo

Doing medical rounds on streets, alleys of Boston

In new book, Tracy Kidder follows ‘Dr. Jim,’ who provides homeless people with health care, prescriptions, hot soup, occasional $5 bill

Excerpted from “Rough Sleepers: Dr. Jim O’Connell’s Urgent Mission to Bring Healing to Homeless People” by Tracy Kidder ’67. Jim O’Connell is a graduate of Harvard Medical School and a professor there. Soon after his residency, in 1985, he became the founding physician of the Boston Health Care for the Homeless. He has worked for “The Program” ever since, both as president and practicing physician. When the following story occurred, he was pushing 70 but was still captain of the “Street Team,” still seeing homeless patients on the streets and in the Thursday Street Clinic, which he had helped create.

Jim once told me that about three-quarters of his job had more to do with social work than medicine. And, he would say, it wasn’t medical school that had trained him for that, but rather the bartending he’d done to put himself through medical school. “If you’re not willing to listen to lots of people talking at you, not all of them coherently, you’ll go crazy tending bar.” Most Street Team patients required lengthy visits, sometimes for medical reasons, more often for moral support. Typically, he’d see five, rarely six, in the course of a Thursday clinic, and finish up by late afternoon. This Thursday, in September 2016, had passed in relative serenity. He was getting ready to head home when his assistant, Julie, called from the waiting room downstairs. A brand-new patient had arrived, asking to see “Dr. Jim.” The man seemed “pretty wild,” Julie said. She gave Jim the name and date of birth: Anthony Columbo. December 19, 1968.

Jim told her to bring the man upstairs to the exam room. He did this with misgivings. He had promised his wife that he’d head for home by four, at the latest five. Maybe he could keep this visit short — simply meet this new patient and arrange to see him on another day.

Jim always stood to greet his patients. He would put on a listening smile for the talkative ones, all the while observing them carefully. The exam room wasn’t much bigger than a janitor’s closet and crammed with basic medical equipment. When this new patient walked in, he made the room seem even smaller. He was taller than Jim, tall enough that Jim had to look up to meet his eyes. He introduced himself as Tony. He had a powerful handshake. Even when he sat down, in the chair beside the doctor’s gray metal desk, he looked outsized. He wore several layers of shirts, but it was clear that he was lean and muscular, much fitter-looking than most rough sleepers who were pushing 50. He brought an odor of sweat and slightly rotten fruit. Several days’ growth of black beard charred his face. He was balding, his hair close-cropped with a few strands stippling his high forehead, which he mopped now and then with a wad of paper towel — sweating either because of all his clothing, Jim thought, or else withdrawal from gabapentin, an anticonvulsive widely used as an ingredient in euphoria-inducing drug cocktails. The man’s face was classically proportioned, with a slightly hooked Roman nose and dark brown eyes, which moved observantly around the room.

Jim asked Tony what brought him here. A torrent of words poured out. His voice was slightly hoarse, with a baritone timbre and a North End variant of the Boston accent. When he said, “Make a long story shawt,” he tended to do the opposite. He said he’d spent 20 years in prison, had been living on the streets ever since, and had been buying the drug Suboxone for a long time, both in prison and outside. Jim often prescribed this rather new drug to help patients wean themselves from heroin. It was in itself only mildly addictive. Tony said he was using it mostly for the pain in his back and knees, and now he was feeling sick from withdrawal — “Subo sick.” He needed some Suboxone now.

Did he use other drugs? Jim asked.

“I do, I do,” said Tony. “I smoke a lot of K2, stuff like that, and coke sometimes.”

On his computer, Jim had located Tony’s medical record, which revealed that he’d been seen sporadically at one of the Program’s clinics, and that he had been prescribed Suboxone for opiate withdrawal. Giving him a prescription was justifiable, but Jim wasn’t sure he ought to do that. Tony might be using Suboxone as a base for a drug cocktail. Jim told him that he could take a urine sample from him now, and then give him a script next week.

Tony’s eyes narrowed. The effect was dramatic. It turned his face dark, like north wind on the ocean. “Well, that was the whole thing,” he said. “That’s why I don’t come to these places.” He moved forward in his chair, about to rise.

“Wait a minute,” Jim said. “Sit down for a minute. Talk to me.”

And Tony sat back down, telling Jim how hard it was to live on the streets, how much pain he was in right now.

There was no mistaking the man’s desperation. Still listening, Jim turned to the computer screen and looked again at Tony’s medical record. The file was scanty, but it confirmed the outlines of what Tony was saying. Jim thought, “If I don’t take the time now to get him his meds, I probably won’t ever see him again.”

If he gave Tony a week’s prescription for Suboxone, Jim asked, would he promise to come back next Thursday?

“Damn right!” said Tony. “That’s what I’m heah for!”

Jim typed the script and handed it to Tony. If Jim had left then, he would have been only an hour late getting home. But Tony said he had another problem. “I don’t have an ID right now.”

Jim’s pager went off, interrupting Tony. It was Jim’s wife. He phoned her. He said he was with a patient, could he call her right back?

“You supposed to leave, Doc?” asked Tony.

Actually, Jim said, he was supposed to have left by four. “But let’s finish this.”

He went with Tony to the CVS pharmacy on Cambridge Street, in order to vouch for Tony’s identity. It was after six by the time they got there. The pharmacist accepted the script. But when he came back, he said there was something wrong with Tony’s Medicaid insurance policy. They wouldn’t pay.

Jim asked the pharmacist how much the script would cost. The pharmacist said $120.

Tony erupted. “Dude! On the street? Five bucks.”

Jim pulled out his wallet and laid his credit card on the counter. “Use this.”

“Whoa! No, no, Doc.” Tony grabbed the card and handed it back to Jim.

Then the pharmacist looked at Jim. “Wait a minute, you’re the doctor? Let me make another call.”

And then finally it was over. Medicaid would cover Tony’s Suboxone after all. As they left the store, Jim asked Tony if he had any money. He didn’t. Had he eaten today?

“Pretty much,” said Tony.

Jim went back inside and bought a sandwich from the cooler, then slipped a $20 bill into the bag, and handed the package to Tony, who protested. Not strenuously, but for form’s sake, it seemed.

Many people disapproved of such gifts, including some members of Jim’s own Street Team — not the sandwich but the cash. Would Tony buy alcohol or drugs with the money?

Jim had resolved that issue for himself years ago, with the help of a formerly homeless patient and a veteran nurse: If he was to give money away, he should do it and privately, so that patients had the power to buy what they wanted, and not what he thought they should buy. He had been following this counsel for decades — giving a dollar at a time at first and now usually a ten or a twenty. For the past few years, the Program had paid him a handsome salary, and the money he slipped into patients’ hands amounted to only a few thousand dollars a year.

Jim and Tony parted at a little after seven o’clock, the big man shambling away down Cambridge Street. Jim later told me that the twenty he’d given Tony was potentially therapeutic, another incentive to return.

***

Six months later, Tony had become a full-fledged Street Team patient, and a regular at the Thursday clinic at Mass General, where he was usually seen by Jim. I sat in on one of the visits, in Jim’s tiny exam room.

Soon after the session began, Jim was called away, and I was left alone with Tony for a little while. He spent the time exalting “Dr. Jim,” calling him the “cawnahstone” of the Program. When Jim reappeared, Tony turned to him and said, “Braggin’ about you, saying you created an army of good people. Let me tell you something about you, Doc …”

“It’s a nightmare downstairs,” Jim said, as he sat down at the desk.

He put a little chuckle in his voice. It sounded forced.

But Tony wasn’t going to let him change the subject. He went on praising Jim. Floridly. All of the Street Team were “angels wit’out wings,” but Jim was “the cawnahstone,” the archangel of the homeless, “creatin’ an army to catch ’em once they fall.”

Jim tried again. “Sweet of you to say that. I wish it were true.”

Tracy Kidder.

Photo by Fran Kidder

But Tony shouted him down. “It’s the truth! I mean, come on! You don’t discriminate, you don’t just treat me, you do this for everybody!”

Some members of Boston’s medical and philanthropic establishments had described Jim to me as “a saint.” Invariably they remarked on his modesty. In fact, Jim practiced self-effacement as if it were a creed. He seemed reflexively uncomfortable with praise, and especially with beatification. He’d quote his former guru, a nurse named Barbara McInnis, who had once told him: “This work is way too interesting to be looked at as saintly.” But the problem with denying you’re a saint is that, in many eyes, it improves your qualifications.

The first few times I had talked to Tony he seemed infinitely distractible. Now, as he continued to extol Jim, it was clear there were subjects on which he would perseverate. I wasn’t sure what had inspired this outpouring. People living on the street are apt to absorb the disapproval that walks by them every day. Tony’s extravagant tribute seemed half-mad in execution, but maybe it was his way of preempting disapproval, from us and from himself — a case of his making himself feel better at the risk of his doctor’s discomfort.

Finally, Jim gave up protesting. And turned to the computer screen hovering over the desk. He stared up at Tony’s medical record. “Tell me how you’re doing. Your blood pressure’s up a littelllll,” Jim elongated the last word, as he often did, as if holding a note.

During Tony’s appointment the previous week, Jim had commented in a completely matter-of-fact tone that there were marijuana and cocaine in Tony’s urine. Today was different. “Your urine’s great, by the way,” Jim said, still staring at the numbers on his computer screen. “Good job.” He put the blood pressure cuff on Tony’s arm and said, “Think good thoughts for a second.” Tony’s pressure had been towering — 172 over 101 — two hours ago, when he first arrived in the waiting room downstairs and the charge nurse had measured it. Now it had fallen to perfection, to 123 over 77. “Tony, you made my day. You made my day.”

“I made his day,” said Tony. “Listen to him. He’s worried about my health more than I’m worried about it.”

“A doctor cares about your health,” said Jim. “What are you talking about here?”

And Tony was off once again, saying that I should grab 10 random homeless people and ask them about Dr. Jim. “They’d all be stories about how the guy has compassion, cares. More than a doctor and more than human.”

“Now you’re gonna give me a big head,” said Jim. “But your urine was great. So what did I miss here? Are you okay with — did you get your wallet back?”

Tony’s office visits had protracted denouements. Always there was the normal complexity of a life on the streets to sort out. Tony had lost all his IDs again, this time when his wallet had been stolen as he slept. At the start of a month, Jim made up a budget for his cash gifts to patients, and he would come to Street Clinic with $5, $10, and $20 bills pre-folded so he could pass them unobtrusively. Tony rarely asked for money. When he did, he promised to pay it back. He hadn’t yet. But now he’d lost everything again, and when Jim handed him a folded twenty, he didn’t even pretend to argue.

Jim always stood to greet his patients. He would put on a listening smile for the talkative ones, all the while observing them carefully.

There was the ongoing quest to find him an apartment, which seemed near fruition at last. There was the weekly refilling of his prescriptions — weekly because an unhoused person has no place to keep medicines and is bound to lose them fairly often. One longtime patient used to hide her pills in her underwear. And there was also Tony’s need for help with fundamental things. Patients often asked for meal tickets and taxi vouchers and $5 gift cards to places such as Dunkin’ Donuts, which conferred both food and use of a bathroom — what a friend of Jim’s called “the right to shit.” Today for Tony, it was subway passes so he could get to the Social Security office to work on getting a new ID. “I hate sneaking on that train. I really do,” he explained, as Jim reached into his doctoring backpack for the passes.

Finally, there was news of the street for Tony to pass on to Dr. Jim. “You heard Johnny Smith died. With the white hair?”

“What?” said Jim. “Oh, man. I had not heard that.” A long pause.

Then he said to Tony, “You’re like my eyes and ears out there.”

“I enjoyed the visit,” said Tony, all six feet four of him arising.

Jim lingered at his desk for a while afterward. He smiled. “Julie and I always take 10 minutes to recover from Tony.”

***

In Jim’s memory, there was a pantheon of vivid and mysterious patients from years past. Two former college professors stood out. Harrison and David. Both had been afflicted by mental illness, David most emphatically and strangely. What psychiatrists call a fixed delusion had warped his life. He believed that he had sired a two-headed child in Vermont and that he was still being pursued for this by people armed with what he called zappers. He could not be talked out of his bizarre fantasy, not by psychiatrists or Jim or a fellow professor friend who came and tried. And yet while living on the streets, David had become a member of a church choir and its social ministry, tutoring various people at the public library. He had doggedly visited a young Black man in jail and had helped to set him free.

As for the older professor — Harrison — he said he’d been the youngest person ever awarded tenure at Columbia University and also that he’d been a friend of Jack Kerouac and the beat poet Allen Ginsberg, among others. Jim had found a trove of evidence that all of this was true. When Jim had told Harrison that he loved Kerouac’s book “On the Road,” the old ex-professor had said, “Jack was a dashing young man but a terribly shallow thinker.”

Jim used to take Harrison and David to lunch once a month at the Union Oyster House. He would listen as they argued philosophical and literary issues — did postmodernism actually exist? The elder, Harrison, would clumsily spill clam chowder all over himself, and Jim would sit there feeling a bit nauseated. Now he’d say that he deeply regretted his squeamishness, that his time with those two men felt precious. Both had died, Harrison some years ago and David just recently, both from natural causes and at what constituted extremely old age for people who live on the streets — that is, for “rough sleepers.”

It was now almost a year since Tony had washed up on the Street Team’s shore, and he seemed with his vividness to have become a candidate for Jim’s pantheon. “I felt there would never be another David, and I felt the same about Harrison when he died,” Jim told me. “I didn’t think there’d be a new one, so Tony is sort of a surprise. He’s different. Harrison and David stood apart from other patients. Not that they were aloof, but they just weren’t part of the rough sleepers’ community. Tony’s in the middle of that vortex. In the time he’s been out of prison he seems to know everyone on the streets.”

In the exam room, awaiting his next patient, Jim offered a few final words about Tony. “He has a code. He’s a bit of an enforcer out there. If you don’t hurt people, you’re okay, but not if you do.”

Gradually, the room itself seemed to calm down — as if it too had a pulse, returning to normal. And then all that remained of Tony for now were a few feathers of down from the holes in his parka, white fluff on the office’s pale green linoleum floor.

Copyright © 2023 by John Tracy Kidder. Published by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.