Book as tree, inside and out

The 160-foot-long scroll is on display at the Arnold Arboretum.

Photos by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Arboretum displays Diane Samuels’ handmade scroll of transcribed Pulitzer-winning, epic conservation saga ‘The Overstory’

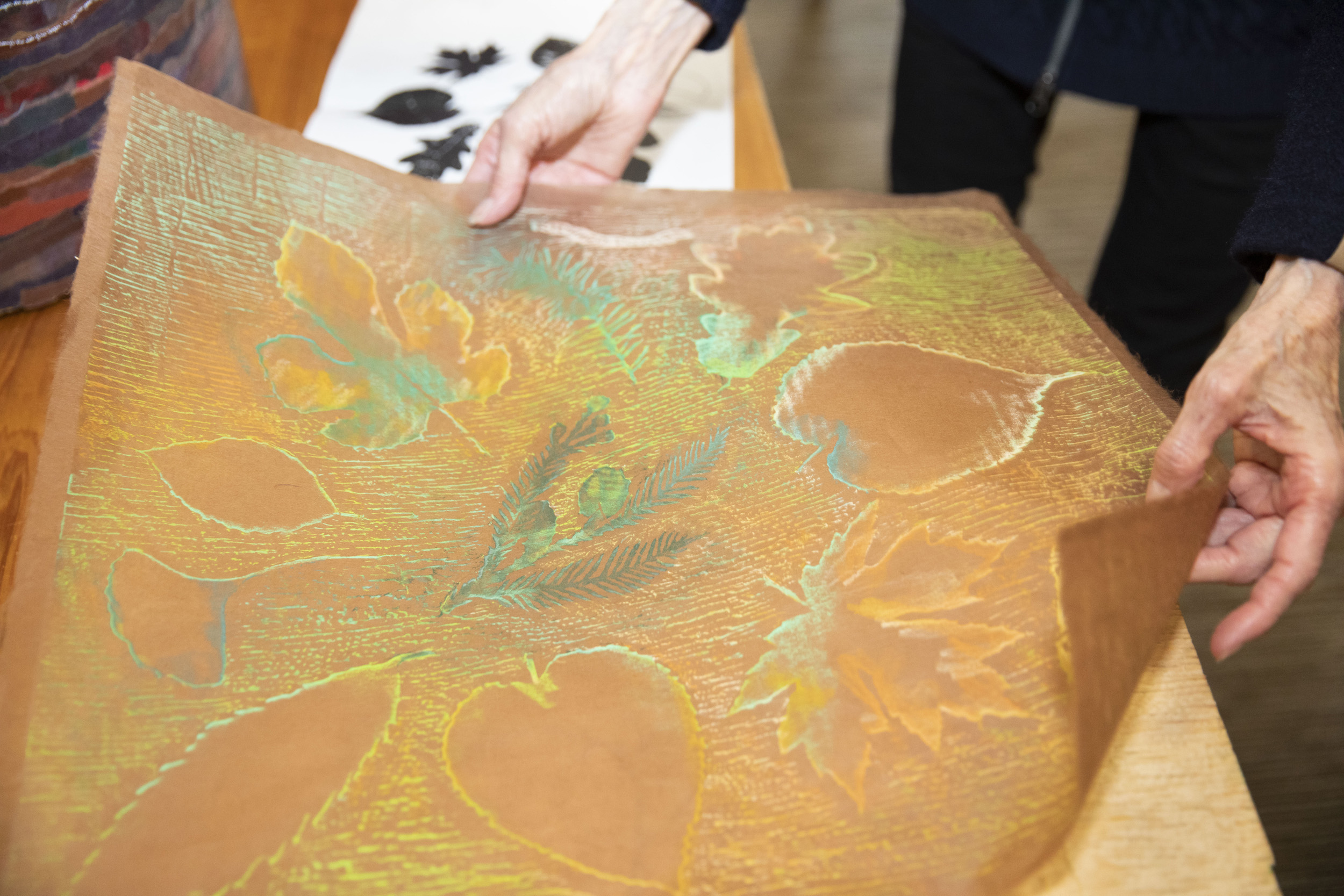

Diane Samuels was eager to get writing, so she took out a sheaf of old drawings, painted them with India ink, and tore them into strips.

Then she glued them to a 160-foot-long substrate created of silk and gampi — a Japanese shrub used in papermaking. Only then did she pick up a pen and begin transcribing the book she’d selected onto the scroll she’d made.

Not many writers have to start by making their own paper, but Samuels counts herself not a writer, but a visual artist. And to her, the paper is part of the point. Samuels sees her mission as honoring the work of writers she admires, and, in 2019, she added Richard Powers’ Pulitzer Prize-winning “The Overstory” to a list that already included “Moby Dick,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Leaves of Grass,” “The Arabian Nights,” and others.

“As an artist, I transcribe books that I love — hand-transcribe them,” said Samuels, who co-founded a nonprofit, City of Asylum in Pittsburgh, to support writers in exile. “The purpose of my life at this point is to honor writers, and to find ways to hopefully entice people to read their books.”

Until Jan. 30, the novel-as-artwork-as-tree is on display in a new exhibition, ‘“The Overstory’ by Richard Powers: Handmade Scroll by Diane Samuels.” It is taking place at an apt spot, the Hunnewell Lecture Hall exhibition space at Harvard’s Arnold Arboretum, a public park, botanical research facility, and 281-acre repository for trees and shrubs from North American and Asia.

Sheryl L. White, the Arboretum’s coordinator for visitor engagement and exhibitions, said she had contacted Samuels in early 2020 about having her visit the Arboretum, but that was derailed by the pandemic. Then, as she was planning events for this year, she realized that Samuels’ work on “The Overstory,” an epic saga of activists and the lumber industry in the Pacific Northwest, would fit well for this, the Arboretum’s 150th anniversary.

“I started seeing images from this and I thought, ‘This is perfect for the Arboretum,’” White said. “It just all came together.”

Samuels counts herself as an avid fan of Powers’ work and, once the 600-plus pages of “The Overstory” were published in 2017, contacted Powers to do a reading for City of Asylum. He agreed and visited the nonprofit and, after a pitch from Samuels, agreed to the scroll project. She said Powers was a generous correspondent over the nearly two years of painstaking transcription that followed.

“I thought it’s kind of a parallel to ‘Moby Dick,’” Samuels said of “The Overstory’s” depiction of characters’ interactions with trees in their lives, including those in danger of being logged. “In the sense of humans’ position in relationship to nature and the vastness of nature and the smallness of the human and the amount of control we actually have; and how fighting, either with a small group or a larger group, winds up derailing lots of things.”

Samuels said she took months to plan the project, wanting each of the book’s sections — root, trunk, crown, and seed — to look different, and creating samples to try out different ideas. Though inspiration played a key role in her artistic process, Samuels said she had another ally: mathematics.

Samuels spent months planning the project, wanting each of the book’s sections — root, trunk, crown, and seed — to look different.

“There’s a lot of planning and, weirdly, a lot of math involved, as far as how long and how wide and how much,” Samuels said. “I’d make some samples and go to bed that night and think, ‘OK, I can get started.’ Then I wake up in the morning and I think, ‘Ugh, no!’”

She eventually did set to work, taking nearly two years to transcribe the book’s 176,000 words. Using an extremely fine nib, she made the white and black inked words part of the art, adorning the scroll in letters so tiny that sentences look like lines from a distance, drawing visitors closer to Samuels’ multicolored, redwood-reminiscent canvas.

“I love the idea of being immersed in a book,” Samuels said of the transcription process, “in the sense that the book is kind of embracing me.”

The result is striking. The scroll is 160 feet long and 20 inches wide, representing the cross section of a small California redwood. The work, which Samuels finished in 2019, has been displayed twice before, at Youngstown State University in Ohio and a museum in Deauville, France.

The scroll is so long that the exhibition features a half-size digital print, displayed on one wall of the room. The scroll itself is on a table in the room’s center. Around the space are several striking prints, enlarged sections of the scroll, something Samuels said has never been done before.

“My favorite is the mycelium. I absolutely adore them,” White said of Samuel’s depiction of tree roots’ fungal partners. “I think it’s because it is this connection to so many things. It’s a connection to art and to science and to trees and to soil and to everybody out there in the world.”