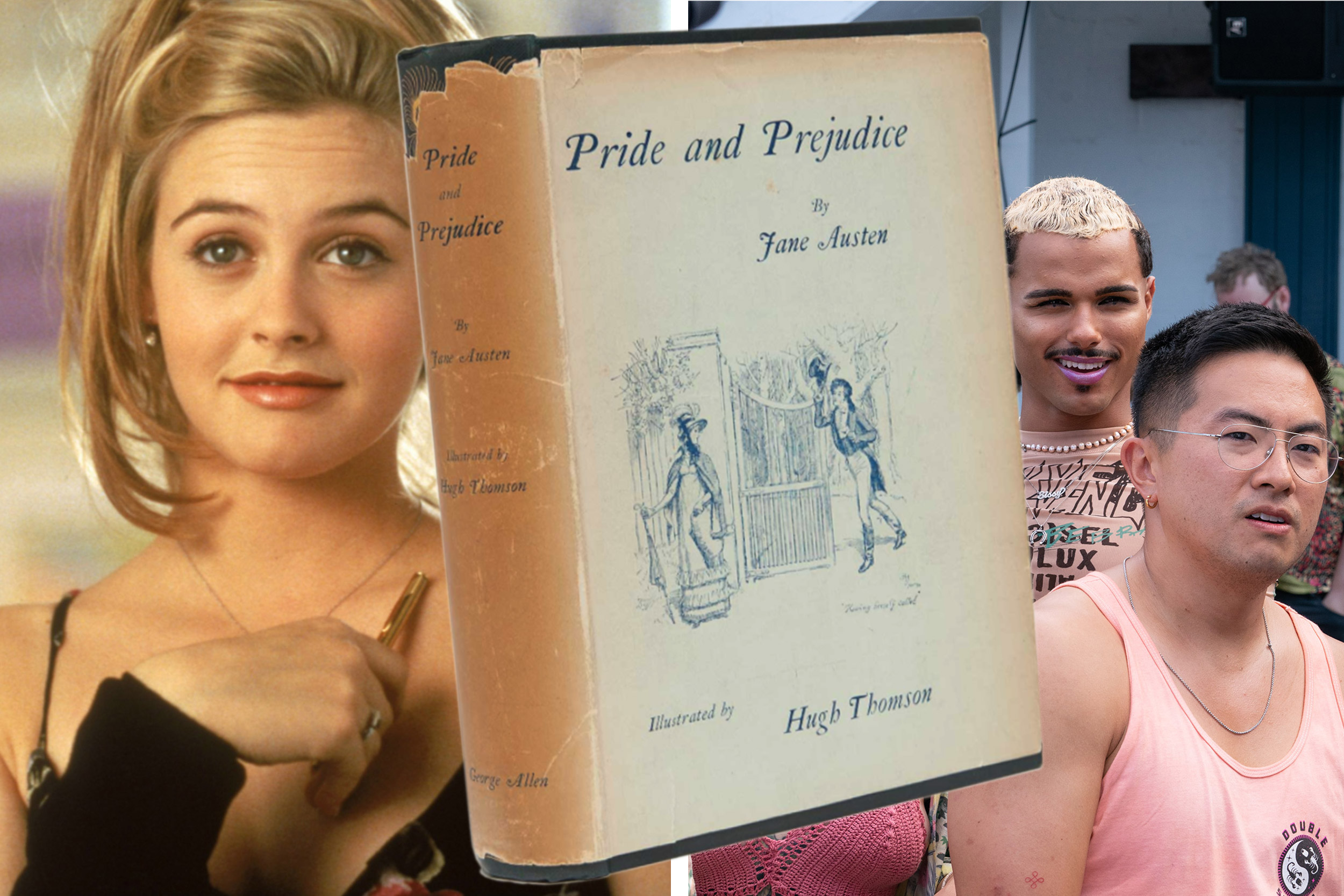

Jane Austen’s works inspired the 1994 movie “Clueless,” based on the novel “Emma.” “Fire Island” offers a passing glance at Austen’s “Pride and Prejudice,” with its observations about class, power, and relationships.

Credit: © 1995 Paramount; Jeong Park/Searchlight Pictures © 2022 20th Century Studios

Feeling ‘Clueless’? Here’s why Jane Austen never seems to get old

‘Pride and Prejudice’ audiences, readers still smile at its razor-sharp observations on money, class, social types

The new queer romantic comedy “Fire Island” features a multiracial cast and a slightly debauched family vacation. It may not closely resemble its literary inspiration, “Pride and Prejudice,” but the movie’s take on Jane Austen’s observations about class, power, and relationships show just how relevant the novel, published in 1813, remains today.

“People think about ‘Pride and Prejudice’ as a love story, and there’s an appeal to a beautiful romance in which two people who are smart and attractive get together at the end,” said Tara K. Menon, an assistant professor of English, who first read the book as a teenager. “But in some ways, this is not a love story at all. This is a story about class and marriage and economic security. It’s really a story about money more than it is about anything else.”

Students in Menon’s courses, including “The Age of the Novel,” learn about the legal and financial realities of Austen’s 19th-century world to better understand her characters’ social and economic decisions. “I provide context about, for example, primogeniture — the law that meant that only firstborn sons could inherit — to show how understanding that law is essential to understanding the social dynamics of the novel,” she said.

Alejandro Eduarte ’23, an English concentrator from Minneapolis, came away from “Age of the Novel” with a range of questions about the relationship between “Pride and Prejudice” and its historical setting.

“It’s a testament to the novel’s greater power that it can still force questions like: How is feminism configured in the novel? What’s going on with the way that the activities of the British Empire are working in the novel? It’s a generative text in that way.”

At the same time, Menon argues that the emotional connection people feel with Austen’s work shouldn’t be dismissed as frivolous. In fact, it is that deep connection that has led to recent adaptations of “Pride and Prejudice” by Curtis Sittenfeld (“Eligible,” featuring magazine writer Elizabeth Bennet living in modern-day Cincinnati) and Uzma Jalaluddin (the contemporary Muslim romance “Ayesha at Last”).

“There was a tendency to dismiss feeling, especially in graduate school, and to talk down to people who said things like ‘I love Elizabeth Bennet’ or ‘I hate Mr. Collins’ — to dismiss that as a really naive and unsophisticated way of talking about fiction,” she said. “Given that so many people read fiction like that, it’s actually more important to try to help people understand why it is that they feel certain ways about the text or the characters in the text.”

The timelessness of the characters — quiet Jane Bennet, blowhard Mr. Collins, fun-loving Lydia Bennet — lends itself well to contemporary adaptations, said Menon. One of her favorite Austen-inspired works is the 1994 movie “Clueless,” based on the novel “Emma,” because of its understanding of social types that transcend time. Another favorite is “Love & Friendship,” a 2016 film by Whit Stillman based on the novel “Lady Susan.”

“If you had to talk about the tone of Austen, I think the word that I would use is something like cruel,” she said. “The humor isn’t gentle, and I think that Stillman’s ‘Love and Friendship’ really understands that.”

Two centuries removed from Austen’s first readers, Eduarte was pleasantly surprised to find that her sharp, arch tone came through in “Pride and Prejudice.”

“So much of the direct speech of characters in the novel, even though a lot of it is filtered through a certain class of people, still rang humorous,” he said. “The way that the novel depicts Lady Catherine de Bourgh, for example — we can still kind of have a hearty, full sense of laughter at her really grandiose proclamations about seemingly every subject on the planet. We all know a Lady Catherine.”

“In terms of adaptations, I can see that people will continue to be endlessly inspired by Austen because even though the novels are, in some ways, so specific to 19th-century England, they’re about characters, and specifically relationships, even aside from romantic relationships, that are a part of almost every culture that I can think of,” Menon said. “I don’t see those things going away anytime soon.”