Elif Batuman returns to Harvard

Author and alum borrowed from her own life, then and now, to pen ‘Either/Or’

Elif Batuman ’99

Photo by Valentyn Kuzan

A lot can change between the first and second year of college — academic pursuits, friendships, romantic desire. In her new novel, “Either/Or,” Elif Batuman ’99 explores these transitions through the eyes of protagonist Selin Karadağ, a Turkish American student who uses literature, language, and philosophy as guideposts for navigating undergraduate life at Harvard.

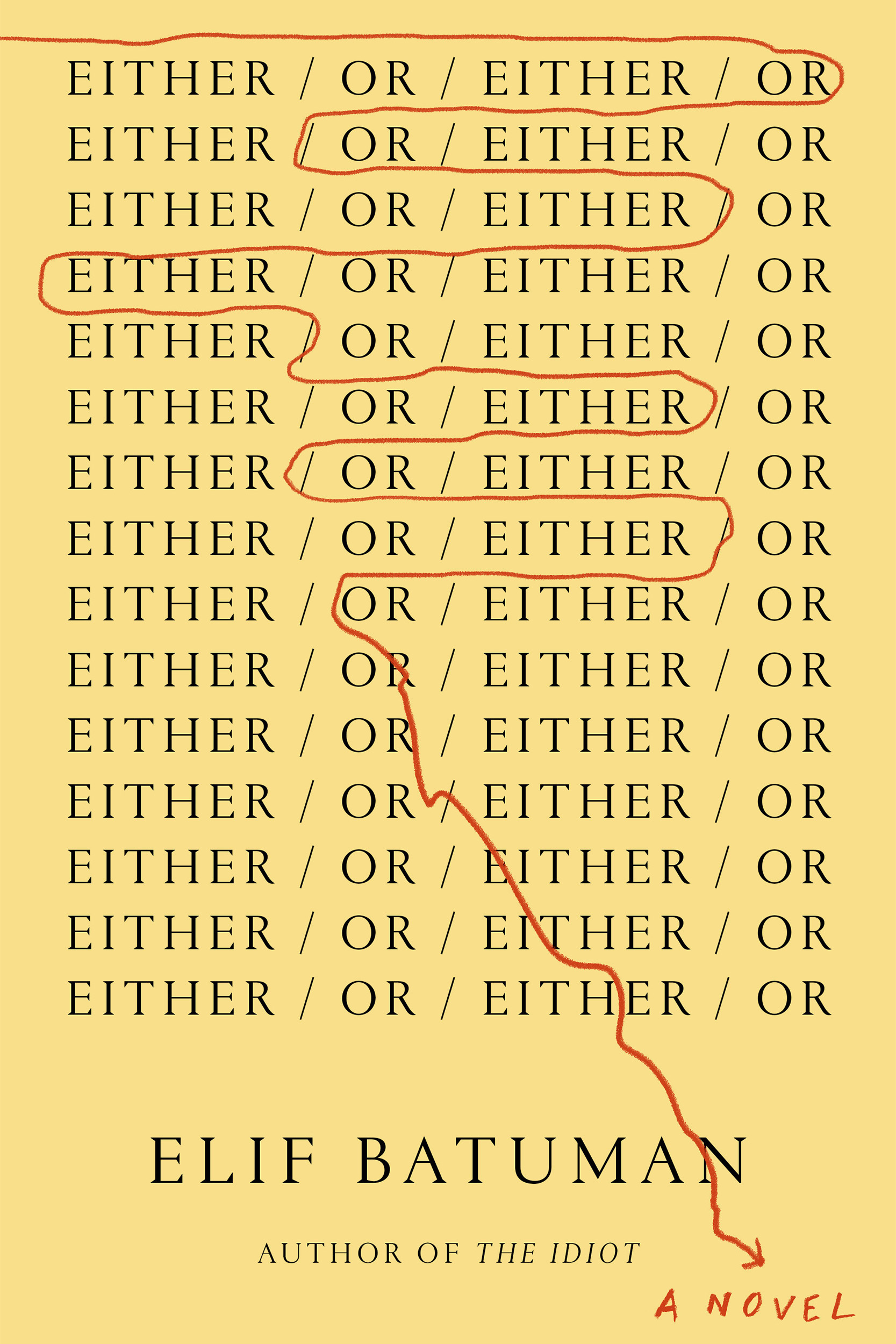

Readers first met Selin in Batuman’s debut novel, “The Idiot,” when she started at Harvard in the mid-1990s. In “Either/Or,” named after the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard’s first major work, published in 1843, Selin goes back to campus for sophomore year, asking big questions about how to live one’s full truth even if that truth isn’t quite yet formed.

Batuman spoke to the Gazette about her writing process, how her own life changes affected Selin’s trajectory, and resisting a clean ending. The interview was edited for clarity and length.

Q&A

Elif Batuman

GAZETTE: What’s the significance of the title?

BATUMAN: “Either/Or” is this book by Kierkegaard that makes a big impression on Selin. It’s about choosing between an aesthetic and an ethical life. Selin and her best friend, Svetlana, have this model of their friendship in which Selin is the aesthetic one and Svetlana is the ethical one. This is one of the most autobiographical parts of the book. I did have a friendship like that, and I did read that book in my second year of college and it was hugely influential. I thought that I would just live my life as if it were a book and then I would be able to write it down.

One reason the title is so compelling to me now is that my thoughts have gone through a lot of changes in the past five or six years. I’ve read a lot more second-wave feminism and some amount of ecofeminism, and I now see these binaries as pernicious. So I now have a lot of issues with the original “Either/Or,” but part of the project for me was to go and see: What is it about those binaries that was so attractive?

GAZETTE: How did Selin change from first year to sophomore year, and how did you change in the period between the publication of “The Idiot” and “Either/Or”?

BATUMAN: Between first and second year of college, there is a huge difference. I felt aware of that as I was writing, and part of what was exciting about coming back to Selin’s voice was getting to see how it grew. The process of writing “Either/Or” was largely about making conscious certain things that I had realized about “The Idiot” while I was promoting it, and that was the extent to which Selin is following certain scripts that she gets from a lot of different places: the books that she’s reading, her friends, her classes, her parents, her family experience. She’s asking herself much more explicitly and directly: What are the different roles that people are following? Why are they doing these things?

I also wrote “Either/Or” at a time when I no longer identified as heterosexual, which came really late for me, at around age 38. I started thinking of myself as queer and my primary relationship is with a woman. Something I read that left a huge impression on me was the article “Compulsory Heterosexuality and Lesbian Existence” by Adrienne Rich. Rich talks about how we think of heterosexuality as a natural choice for most women, and actually that, as seemingly natural or free or inborn as that choice is, it can also be seen as a product of a lot of ideology and ideological training. That really resonated for me. When I thought back, I could suddenly recognize how hard I tried to belong to this ideology and fit this particular narrative. So it was really exciting for me to get to go with Selin and to have her questioning all these things.

“How much of what we do that we think we’re choosing freely is a script that we’re actually going to throw a lot of work into to follow, and to what extent is that script serving what we really want and serving our freedom?”

GAZETTE: Neither “The Idiot” nor “Either/Or” follows a conventional plot structure, with a tidy ending. What motivated that choice?

BATUMAN: One thing I really wanted to explore was how I came out of college in the ’90s with certain ingrained beliefs that I thought I had chosen very freely. Certain aspects of my identity — like that I’m a literature person and not a politics person; that the most important thing to me is the novel; that the novel is universal not political; that novels are about love; that love is about something that ultimately involves penetrative intercourse between a man and a woman. How did I get all of those ideas? Why did they seem right to me?

I wanted to understand how a reasonable, good faith person could reach these conclusions. That was much more valuable than writing it in a more utopian way or writing it in a way that was more like “Here’s what I wish I could have known.” Because the point of writing it for me is to invite readers to ask themselves the same kinds of questions that I’m asking about my past, to ask about their past or their present. How much of what we do that we think we’re choosing freely is a script that we’re actually going to throw a lot of work into to follow, and to what extent is that script serving what we really want and serving our freedom?

GAZETTE: Will we see more of Selin in the future?

BATUMAN: There’s a Selin novella coming out, set in 2000 and 2001, where she is trying to write a novel about everything that happened in “The Idiot” and running into problems. I don’t think there’s going to be a book about junior year and senior year because I would die of old age first. I’m working on some material based on some time I spent in Turkey in my 30s, and I’ve been thinking that I might want to revisit that from Selin’s perspective because the Selin voice lets me ask questions instead of having the answers already, and I’ve been finding that really freeing and exciting.