At the International Women’s Year conference in Houston in 1977, attendees hold clashing signs on abortion rights.

Photo by Bettye Lane; courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

How Roe got to be Roe

Schlesinger Library holdings document long, pitched dispute over abortion in archival documents, photos, letters, voices of women

It’s a safe bet that interest in Roe v. Wade won’t decline any time soon. Friday’s release of the Supreme Court decision overturning the landmark 1973 ruling guaranteeing the right to abortion has sparked ongoing protests around the nation. Public dialogue in the media and in local forums about the issue was already at a fever pitch, owing to the May 2 leak of a draft of the decision.

The battle over women’s reproductive rights has been long and contentious. And while Roe has been the law of the land for half a century, it’s clear that the issue was not settled in the minds of all Americans. Collections at the Schlesinger Library at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute document the abortion dispute in the U.S., providing rich historical and political context and offering insights into the evolution of one of the nation’s most stubbornly polarizing issues.

The holdings of the Schlesinger, a research library on the history of women in America, include archival materials that chronicle the dispute from both the abortion rights and the anti-abortion movements, said Jenny Gotwals, Johanna-Maria Fraenkel Curator for Gender and Society there. Among them are photographs, records of abortion-rights organizations, posters of anti-abortion advocates, and personal letters of women asking for help to terminate their pregnancies as well as personal papers and documents of anti-abortion activists.

“One of the most interesting aspects of our collections on women’s reproductive rights is that they span the very personal and very public,” said Gotwals. “We know that in order for historians to tell the whole history of the conflict over abortion, we must have archives that document people who are coming to this issue from different standpoints.”

Surgeon and anti-abortion activist Mildred Jefferson, the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School, is asked to leave the conference hall at the International Women’s Year summit in 1977.

Photo by Bettye Lane; courtesy of Schlesinger Library, Harvard Radcliffe Institute

Recently, the library acquired from The Sisters of Life the Joseph R. Stanton Pro-life Collection, with more than 300 cartons of additional archival materials and rare periodicals and books documenting the movement. Another important and heavily used collection is that of surgeon and anti-abortion activist Mildred Jefferson, who in 1951 became the first Black woman to graduate from Harvard Medical School. Her papers include biographical materials, writings, memorabilia, and speeches.

Jefferson, who founded the National Right to Life Committee in the early 1970s, was a gifted orator and has been credited with persuading Ronald Reagan to become an opponent of abortion. One of her speeches, which has been digitized and posted online, highlights her passion and engagement. “We don’t want people in this great land of ours to become accustomed to the willful slaughter of the innocent,” she said at the 1976 National Right to Life conference. “We don’t want them to become accustomed to the fact that some may sleep and not notice that the right to life has been canceled for the unborn child.”

More materials will be available in the exhibit the Schlesinger Library will launch in October about the landscape of abortion rights in the 50 years since Roe. The exhibit will include video footage from events such as rallies organized by the National Association for the Repeal of Abortion Laws and Americans Against Abortion. It will also feature images of clinic interiors, photographs of protests, flyers, signs, personal accounts of abortion, and political memorabilia. It will cover the whole spectrum of the abortion contest in the U.S., said Gotwals. “It has been a real conflict for 50 years between people working to restrict women’s ability to have an abortion and people working to establish and guarantee that as a legal right,” she said.

Another important collection is that of the Society for Humane Abortion led by Patricia Maginnis, Lana Clarke Phelan, and Rowena Gurner, who traveled around the country to educate women about the procedure in the mid- to late 1960s. The three were pioneers in the struggle to secure women’s rights to have safe and legal abortions. Papers donated by the society include dozens of letters written by women — but also husbands, parents, and boyfriends — asking for guidance on how get an abortion in the late 1960s, before it was legal in the U.S. Due to privacy concerns, the letters have not been digitized but are available at the library.

Some of the letters are written by hand, others on typewriters; all convey urgency and desperation. A 42-year-old mother of three wrote she couldn’t afford to have one more child and asked for help getting an abortion. A husband at the end of his rope said, “We have all the children we need and would like the present pregnancy terminated.” A couple in their 40s who were expecting their first grandchild said they were “frantic” because “to have one more child is unthinkable.”

The Society for Humane Abortion collection is one of Gotwals’ favorites because it documents the efforts of three ordinary women who were passionate about helping women secure abortions in a time when there was much less national attention on the issue.

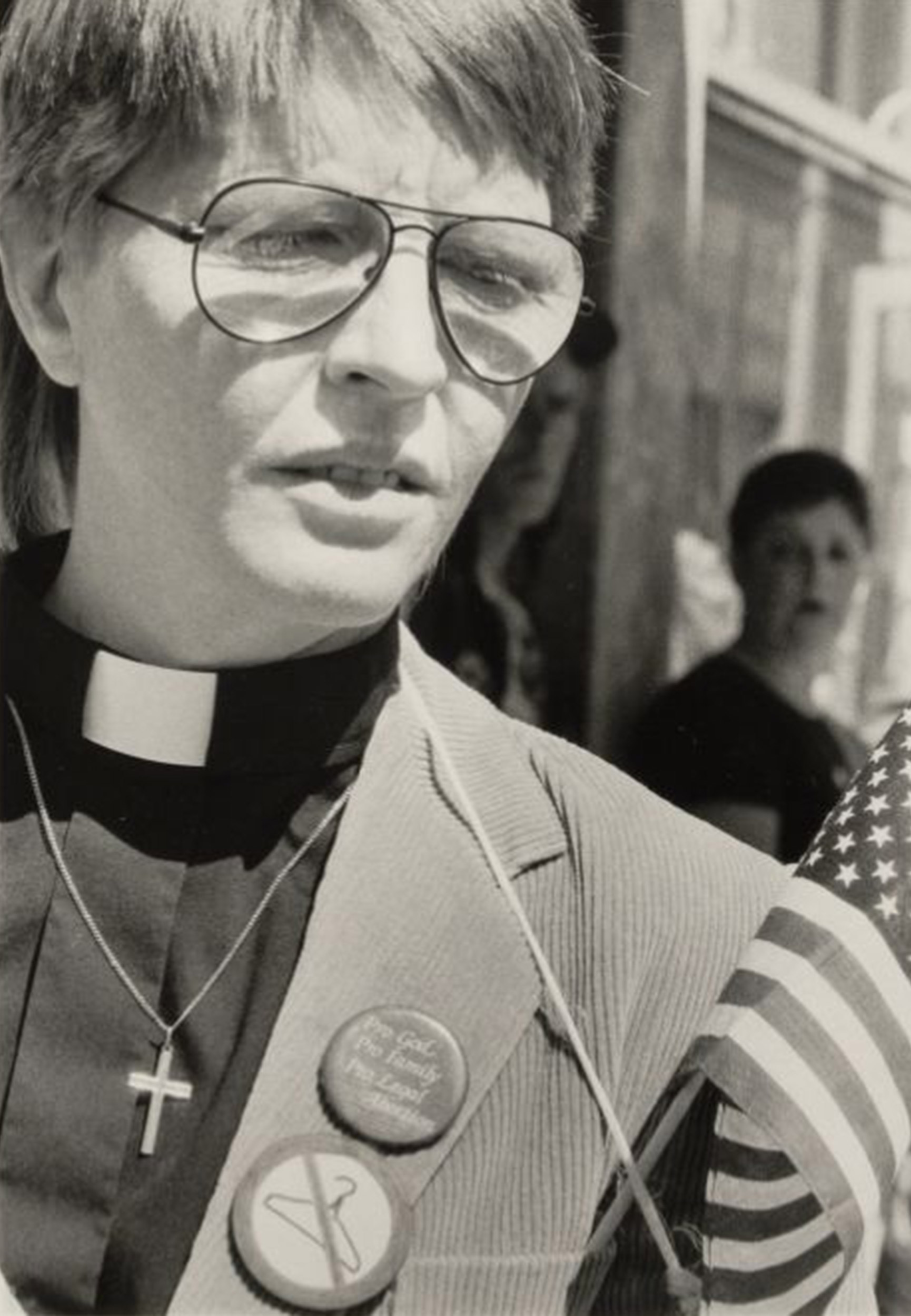

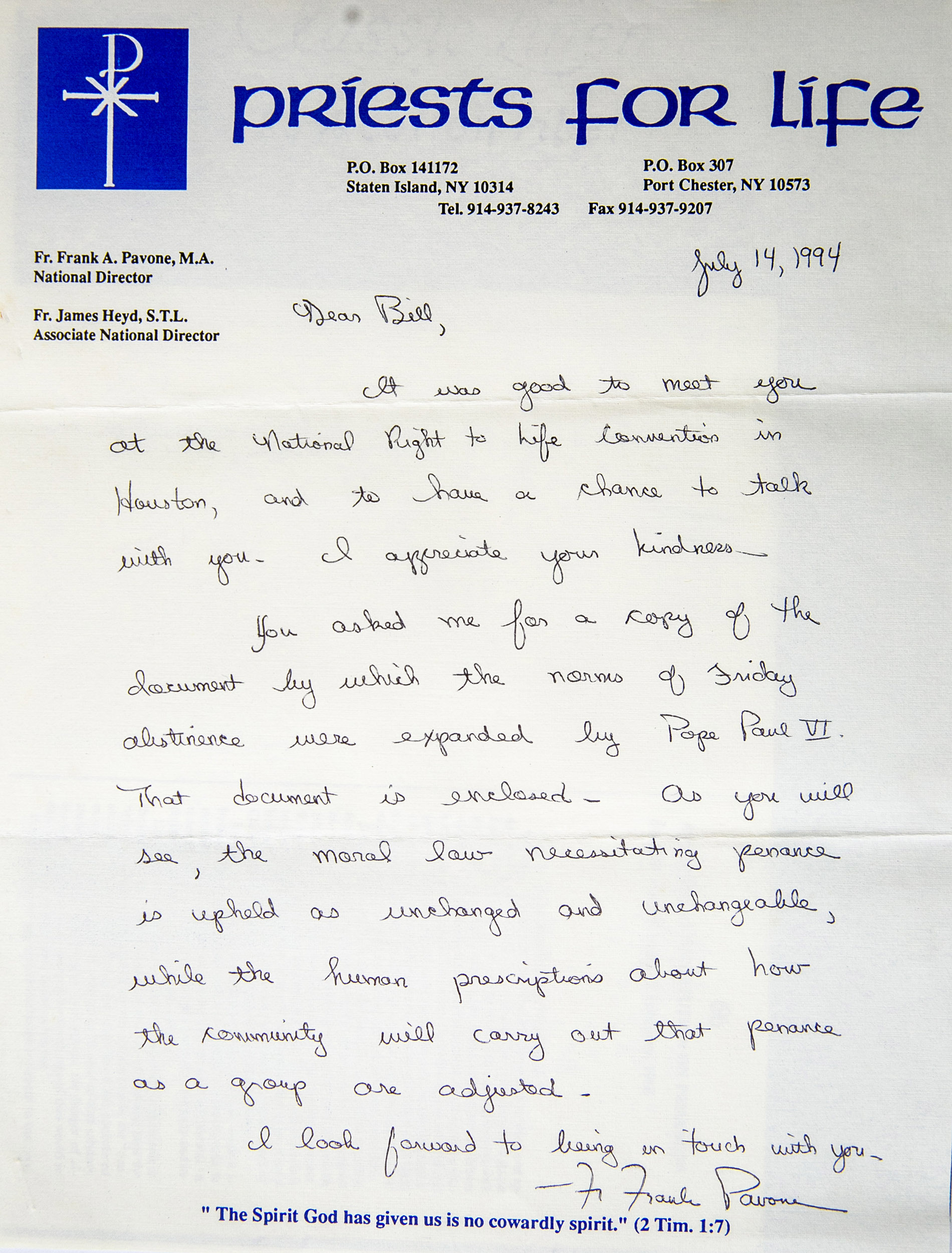

Letters between Priests for Life founder Frank Pavone and abortion-rights activist Bill Baird offer an example of civil debate on the issue.

Photos by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer; courtesy of Bill Baird Papers, Schlesinger Library

Another important holding involves letters between abortion-rights activist Bill Baird and Father Frank Pavone, founder of Priests for Life, which are part of the Baird papers held by the Schlesinger.

The letters underscore the importance of civility in the abortion debate. Baird, whose women’s health clinic was firebombed in 1979 by anti-abortion activists, wrote a letter to Pavone asking him to “appeal to your flock to stop hate speech.” Pavone dedicated a photo of the two, “To my brother Bill, who is as valuable to me as the children I speak for.” (Baird also kept photos of the two.)

Pavone sent birthday and Christmas cards to Baird, who opened the nation’s first reproductive health clinic in 1963 and attended the National Right to Life Convention for nearly 30 years — which Pavone amicably picketed at lunch break.

“Baird was a victim of violence, but he was able to work with Pavone, whose views were totally opposite of his,” said Gotwals. “It shows that a dialogue between two people who have diametrically opposing political beliefs is possible.”

To help researchers and the general public explore the Schlesinger’s extensive collections that touch on the history of abortion, Gotwals suggests starting here.