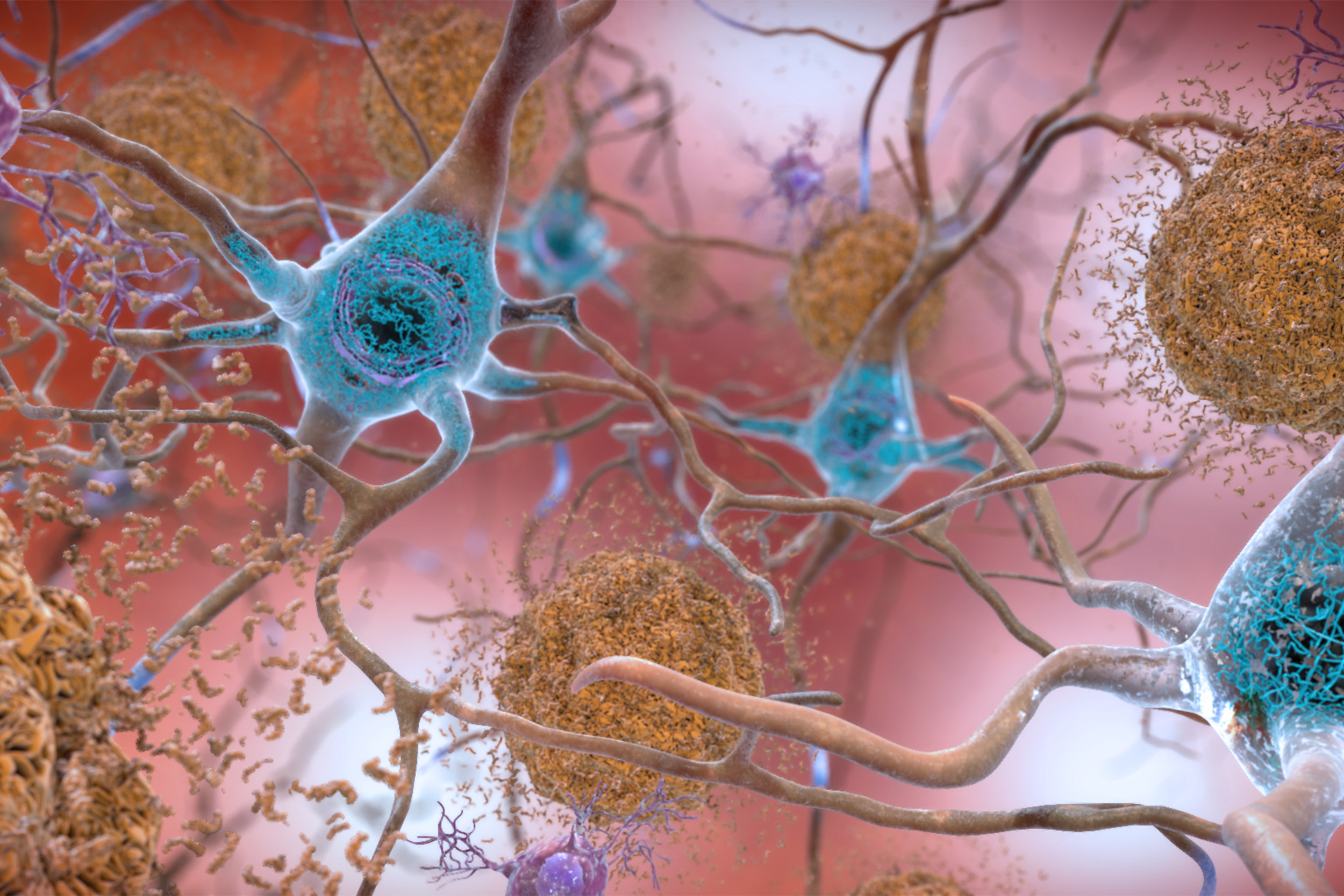

This illustration shows the two main forms of disruptive protein clumps found in the brains of people with Alzheimer’s disease: beta-amyloid plaques (seen in brown) that collect between neurons and disrupt cell function, and tau protein tangles (seen in blue) that build up within neurons, harming synaptic activity.

Credit: National Institute on Aging, NIH

Hallmarks of Alzheimer’s found well before diagnosis

Accumulation of amyloid-β and tau proteins are related to brain network changes years before symptoms

A new study led by investigators at Massachusetts General Hospital shows that early accumulation of amyloid-β and tau protein begins to disrupt the brain’s connections important for memory years before signs of cognitive impairment were observed. The findings may lead to strategies that could help detect the condition early.

For years, researchers have known that amyloid-β and tau pathologies, the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease, can cause the death of neurons — the brain’s most abundant cells — which eventually leads to impairment and dementia. “But we did not know how the brain’s connections respond to the accumulation of these proteins very early in the disease process, even before symptoms,” explains Yakeel Quiroz, senior author of the article published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Quiroz is an investigator in the departments of psychiatry and neurology and the director the MGH Familial Dementia Neuroimaging Lab, and the Multicultural Alzheimer’s Prevention Program.

To learn more about this phenomenon, Quiroz and colleagues used positron emission tomography (PET) for tau and amyloid-β, and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to study how Alzheimer’s disease pathologies related to connectivity of brain regions and networks in individuals from a large family of more than 6,000 living members with Alzheimer’s disease prevalence from Antioquia, Colombia, South America.

Those who have the mutation known as Presenilin-1 E280A) are almost certain to develop Alzheimer’s disease dementia, usually showing signs of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) at age 44 and dementia by the age of 49. None of the individuals studied had any cognitive symptoms yet. Quiroz and her colleagues have formed a unique relationship with this Colombian kindred over the years, ultimately creating the COLBOS (Colombia: Boston) study in 2015 to learn more about how the disease progresses before cognitive impairment emerges and find sensitive biomarkers for predicting who is at high risk for dementia.

“This discovery improves our understanding of how [Alzheimer’s disease]-related pathology alters the brain’s functional organization years before cognitive impairment occurs.”

Yakeel Quiroz, senior author of the study

Previously, this research team showed that these individuals exhibit high levels of amyloid-β almost two decades before the onset of MCI, and tau pathology close to six years before onset. “Studying this unique population can really help us understand how amyloid-β and tau pathologies could affect how the brain communicates years before individuals develop dementia,” says Edmarie Guzmán-Vélez, co-first author of the paper.

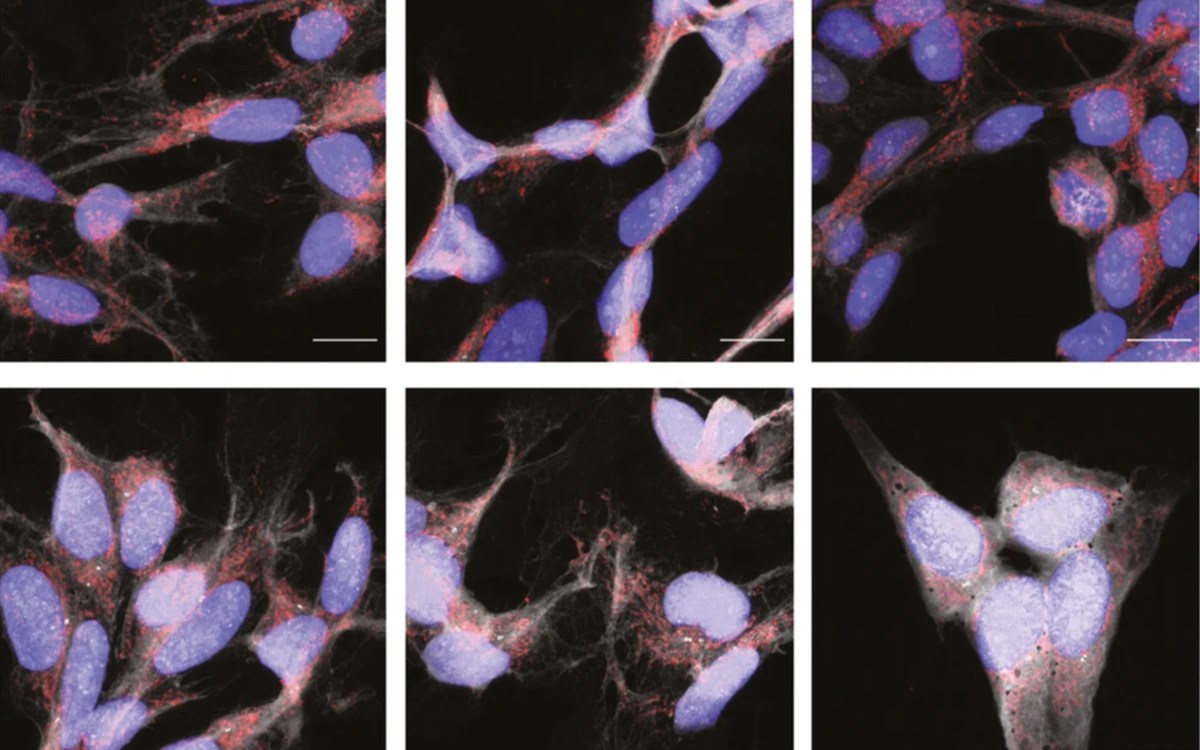

The team used fMRI to examine regions of the brain at the voxel level, akin to pixels that represent 3D units encompassing millions of brain cells, to look at connectivity within and between different networks of the brain. They learned that mutation carriers displayed connection disruptions in the brain’s main memory network years before onset of cognitive impairment in the family. The researchers also developed a novel mathematical approach mering both fMRI and molecular imaging to see more clearly when brain regions begin to disconnect during the disease process.

“This mathematical approach showed how functional dysconnectivity of a memory network was explained by early stages of tau pathology,” says Ibai Diaz, co-first author of the paper. These findings suggest that functional disconnections are evident once tau starts to accumulate in the brain and before brain atrophy, a sign of neurodegeneration, is detected.

“This discovery improves our understanding of how AD-related pathology alters the brain’s functional organization years before cognitive impairment occurs,” says Quiroz. “These findings are exciting because they also suggest that fMRI could be used in the future to identify people who may already have Alzheimer’s disease pathology in their brain and may develop dementia in the future, though more research is still needed.”

The researchers hope this insight will instill a level of urgency and importance about preclinical and clinical trials for Alzheimer’s disease, particularly those targeting disease prevention. Adds Quiroz, “We know now that a lot of things are happening in the brain of those at risk for Alzheimer’s disease, even before signs of memory impairment, so we hope findings like these can improve our understanding of preclinical AD and help improve selection of those who would benefit the most from participating in clinical trials.”

Jorge Sepulcre is co-senior author. Funding for this research was provided by awards from the National Institutes of Health, a grant from the Alzheimer’s Association, the Massachusetts General Hospital Executive Committee on Research ECOR, and an MGH Research Scholar Award.