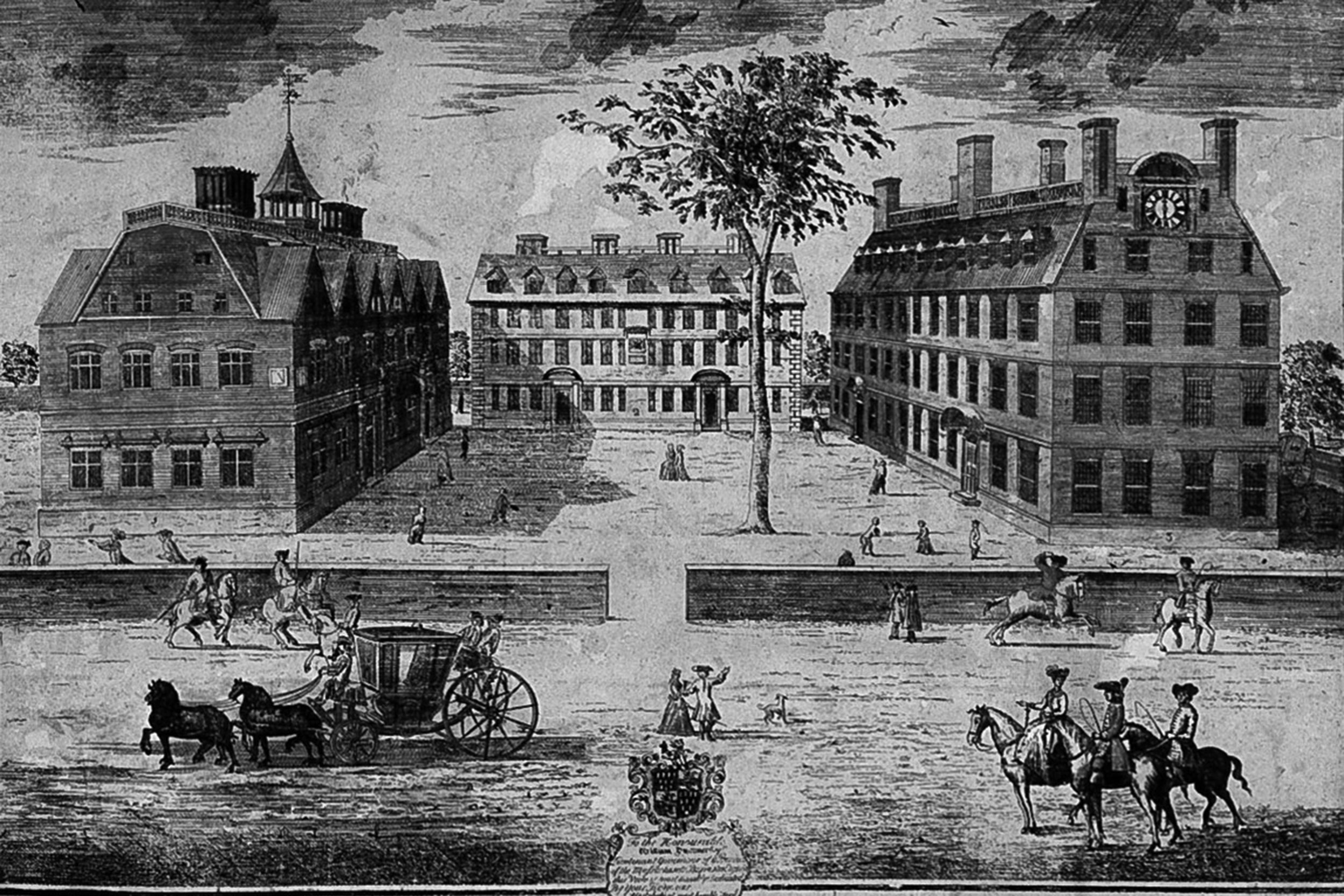

William Burgis engraving of campus from 1726.

Dual message of slavery probe: Harvard’s ties inseparable from rise, and now University must act

President and Corporation dedicate $100 million to implementation of recommendations

A new report shows that Harvard’s ties to slavery were transformative in the University’s rise to global prominence, and included enslaved individuals on campus, funding from donors engaged in the slave trade, and intellectual leadership that obstructed efforts to achieve racial equality.

The report of the Presidential Committee on Harvard and the Legacy of Slavery, released Tuesday, describes a history that began with a Colonial-era embrace of slavery that saw more than 70 people enslaved by Harvard presidents and other leaders, faculty, and staff. The report offers a series of recommendations — already accepted by Harvard President Larry Bacow — that amount to a reckoning with the University’s history. A $100 million fund established by the Harvard Corporation to implement the recommendations includes resources both for current use and to establish an endowment to sustain the work in perpetuity.

“Veritas is more than our motto,” Bacow said in a video accompanying the report’s release. “It’s our reason for being. We’re committed to truth for the sake of our community and for the sake of our nation. The truth is that slavery played a significant part in our institutional history.”

Harvard’s slavery ties extended beyond abolition in Massachusetts, in 1783, through the pre-Civil War period, when wealthy donors boosted the University with funds earned through slave trading and slavery-dependent businesses, such as Caribbean sugar and Southern cotton. The effects carried into the post-slavery era and the 20th century, as prominent faculty members promoted eugenics, discrimination tainted admissions and housing, and Harvard became one of the nation’s most prestigious institutions by catering to America’s white, wealthy upper class. Despite recent efforts to address this history, legacies of slavery persist today.

“There is no statute of limitations on facing the past and determining what it might mean for the present and future,” said committee member Tiya Miles.

File photo by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The report is the result of a nearly 2½-year effort by a faculty committee led by the legal scholar and historian Tomiko Brown-Nagin, dean of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. In addition to highlighting the institution’s ties to slavery, the committee notes Harvard’s connection to prominent abolitionists and African American leaders. The scholar, author, and civil rights pioneer W.E.B. Du Bois was a graduate of the College and the first African American to earn a Harvard Ph.D. Harvard-educated Black lawyers Charles Hamilton Houston, William Hastie, and William Coleman worked against segregation, paving the way for the landmark Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education, which marked the beginning of the end of “separate but equal” in the U.S.

“The committee thought that it was important to lay bare the difficult aspects of Harvard’s history, but also speak to the resistance that is very much a part of Harvard’s legacy,” Brown-Nagin said. “I am aware that the history we trace in this report is deeply troubling. But it would be a great disservice to our community if the only message that we took away was one of shame. We must acknowledge the harm that Harvard has done. But it is also important that we do not — as has been done in the past — bury stories of Black resistance, excellence, and leadership. These women and men are also part of our history — also part of our legacy.”

Much of this resistance defied an official attitude toward equality that well into the 20th century could be described as “a half-opened door,” according to an author cited in the report. It wasn’t until the 1960s that the University initiated a period of slow reform.

“What I think is the most powerful finding is that slavery permeated almost everything about Harvard’s early history,” said Sven Beckert, Laird Bell Professor of History and a member of the faculty committee. “The second thing is the long legacy of this history of enslavement and the importance of Harvard in permeating ideas of racial difference, and also having policies that were based on such beliefs, namely excluding African American students from the University for an extremely long time.”

“There is no doubt that infusions of slavery-tainted money put the School on the path to becoming the institution that we know today: one of the premier universities in the world,” said committee member Annette Gordon-Reed.

Courtesy photo

The report is the latest step in a wider movement. In addition to findings at Georgetown and Brown University, more than 80 institutions have joined a consortium called Universities Studying Slavery. Harvard’s effort has its roots in a 2007 history seminar in which Beckert asked students to plumb the archives for a full accounting of the extent to which the University benefited from slavery. The findings of that report led President Drew Faust in 2016 to erect a plaque outside of Wadsworth House honoring four enslaved people known only by their first names — Titus, Venus, Bilhah, and Juba — who worked for two of Harvard’s slave-owning presidents, Benjamin Wadsworth and Edward Holyoke. Harvard Law School subsequently wrestled with the legacy of a key donor, Isaac Royall, who was deeply involved in Caribbean slavery.

“There is no statute of limitations on facing the past and determining what it might mean for the present and future,” said committee member Tiya Miles, Michael Garvey Professor of History, Radcliffe Alumnae Professor, and director of the Charles Warren Center for Studies in American History. “The present moment seems especially urgent, though, for conducting and sharing research of this kind. The U.S. has been embroiled in a divisive debate about race and the historical legacies of slavery over the last few years. By engaging with the history of our University as it intersects with these issues, we join our collective and institutional voice to a pressing national conversation.”

Donors and slave money

Among the report’s findings is that more than a third of the funds donated or pledged to Harvard in the first half of the 19th century came from five men whose fortunes derived from slavery in some form: James Perkins, Benjamin Bussey, John McLean, Abbott Lawrence, and Peter Brooks.

“Any effort to confront and reckon with the past requires knowing the past and knowing the legacies of the past into the present,” said committee member Martha Minow.

File photo by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The gifts supported Harvard’s expansion from a regional institution that had educated Boston’s elite for a century and a half into a national one. The mark of slavery was clear. Perkins was directly involved in Caribbean slave trading. Bussey was a sugar, coffee, and cotton merchant, crops dependent upon slave labor. McLean conducted business along two legs of the infamous triangular trade, sending wood and food to the Caribbean and bringing the region’s main export, slave-grown sugar, to Europe and the U.S. Abbott Lawrence operated cotton textile factories that depended on slave-produced Southern cotton. And Brooks became New England’s richest man by insuring ships that plied the trade between New England and Caribbean slave islands.

“We can’t say that Harvard would not have existed in some form without donations from enslavers and slave traders,” said Annette Gordon-Reed, the Carl M. Loeb University Professor and a member of the committee. “But there is no doubt that infusions of slavery-tainted money put the School on the path to becoming the institution that we know today: one of the premier universities in the world.”

Gordon-Reed said the report’s significance lies not just in its facts — some of which have been previously published — but in the totality of the picture it paints. It’s also important to understand, she said, that though Harvard today proudly points to its abolitionists and civil rights pioneers, in their time these scholars often felt unwelcome at the institution that would later celebrate them.

“We often take credit for the fact that people who spoke against slavery and for racial equality were at the school, but we don’t talk enough about how they — I’m thinking of Du Bois’ experiences — were treated when they were here,” she said. “Because those people are now admired, Harvard gets the benefit of their courageous moral stances. I think the power of the report is in the accretion of all of the information about the various ways that slavery and white supremacy shaped life at Harvard and shaped the institution.”

“What I think is the most powerful finding is that slavery permeated almost everything about Harvard’s early history,” said committee member Sven Beckert.

File photo by Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

The depth of Harvard’s connections to slavery is evident in the familiarity of some of the names in the report. They adorn buildings and are prominent in the University’s lore: Winthrop, Perkins, McLean, Lawrence, Bussey, Atkins, Greenleaf, Agassiz, Holmes, Warren, Eliot, and Lowell.

“The report reveals that Harvard was not an ivory tower set apart from the dirty dynamics of racial prejudice and racial animus,” Miles said. “It was, and still is, caught up in the struggles of the country and wider world. Harvard has a big history that includes grave mistakes and inspiring triumphs. We can become a more reflective, more intentional, and ultimately stronger community if we recognize both these truths.”

Moving forward

In a message to the community on Tuesday, Bacow noted that legacies of slavery, at Harvard and across the nation, have contributed to inequality in education, health, income, and social mobility. The $100 million commitment, he said, is a response to the profound harm documented in the report.

“I recognize that this is a significant commitment, and for good reason. Slavery and its legacy have been a part of American life for more than 400 years. The work of further redressing its persistent effects will require our sustained and ambitious efforts for years to come.”

Committee member Martha Minow, Three Hundredth Anniversary University Professor and former dean of Harvard Law School, said that the persistence of Harvard’s efforts will be key. “Success here will not happen next week, it is about the long haul,” said Minow, who will chair a committee overseeing implementation of the report’s recommendations.

The recommendations include identifying and offering support to direct descendants of slaves who worked on campus or were owned by Harvard leadership, faculty, or staff. Engagement will include educational support, information-sharing, programming, and relationship-building. Descendant communities affected by Harvard’s practices, either directly or indirectly, are another focus of the recommendations, which suggest establishing “close and genuine partnerships” with relevant schools, community groups, tribal colleges, universities, and nonprofits. Efforts would touch areas such as teacher training, early childhood development, and STEM education.

Redressing Harvard’s links to slavery “will require our sustained and ambitious efforts for years to come,” said President Larry Bacow.

File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

The report also recommends that Harvard establish long-term partnerships with historically Black colleges and universities, including through visiting faculty appointments and a “Du Bois Scholars Program.” Another potential collaboration would focus on libraries and the preservation and digitization of African American history.

On campus, Harvard should honor enslaved people through memorialization, including “a permanent and imposing physical memorial, convening space, or both,” the report says.

“The commitment to truth, truth-seeking, truth-telling — the watchword of Harvard and the guiding light of a research university — requires facing the truths and facing the actual history,” Minow said. “Any effort to confront and reckon with the past requires knowing the past and knowing the legacies of the past into the present. This is foundational work for the work to come.”