War photographer Lynsey Addario at work in the Korengal Valley, Afghanistan, in 2007. “I wouldn’t be risking my life if I didn’t believe in the power of photography.”

Power of photography

Pulitzer-winning war photojournalist Lynsey Addario says in Hofer Lecture her goal is to shake up, educate

Lynsey Addario was kidnapped by Moammar Gadhafi’s soldiers in Libya in March 2011, along with three other New York Times journalists. The Pulitzer Prize-winning photojournalist feared she was likely going to die.

Addario and colleagues Anthony Shadid, Stephen Farrell, and Tyler Hicks were covering the rebel forces who were trying to oust Gadhafi and were caught in a “wall of bullets” between the rebels and Libyan soldiers in the eastern city of Ajdabiya. Pro-Gadhafi forces captured the group and beat, blindfolded, and threatened them with death. Six days later the Libyan government released the four.

Addario has photographed nearly every major conflict and humanitarian crisis over the past 15 years, from Afghanistan to Iraq, from Darfur to Libya, from Syria to Lebanon, from South Sudan to Somalia and Congo. She says her work aims to document the horrors of war and the many ways people try to survive and preserve their humanity even in the darkest of times. Addario recounted the story of her kidnapping in Libya, along with her more recent work in Ukraine, during Houghton Library’s Philip and Frances Hofer Lecture last week.

View this post on Instagram

“I wouldn’t be risking my life if I didn’t believe in the power of photography,” said Addario, speaking from Ukraine, where she’s covering the Russian invasion for The New York Times. “It does have the power to change the course of a war or at least influence the decisions of policymakers. It’s very important for the international community to see the images of war crimes.”

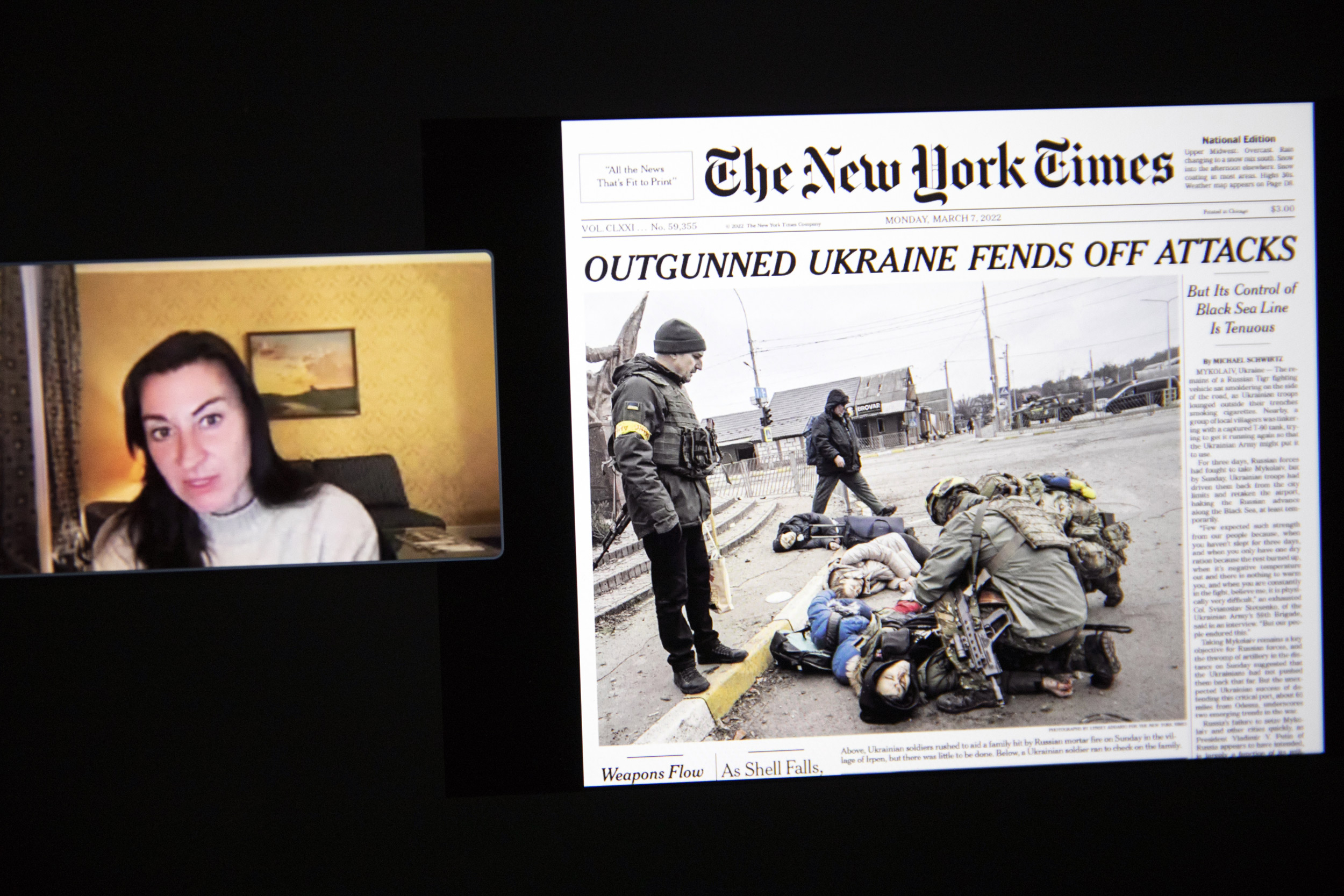

As recently as February, Addario captured the tragedy of the Russian invasion in Ukraine in a harrowing, now-famous photograph of a mother, her two young children, and a family friend lying dead on a street in Irpin, outside Kyiv. The group died in a Russian mortar attack as they were attempting to reach an evacuation route into Kyiv. Addario, who was 20 meters away when the round hit, has called the family’s killing a “war crime.”

“I was surprised and grateful to The New York Times for putting the picture on their front page because it really opened the discussion about the targeting of civilians by the Russian military,” said Addario.

In her lecture, “Of Love and War: Stories of Tragedy and Resilience from Across the World,” Addario presented a personally curated selection of her work, which included all major conflicts and humanitarian and human rights crises around the world she has covered since 9/11. Some of the photographs she shared with the audience are posted on her personal website. The powerful images depict the lives of women under the Taliban in Afghanistan, the Iraq war and the fall of Saddam Hussein, the genocide in Darfur, and the effects of climate change in the Amazon, among others.

“I was surprised and grateful to The New York Times for putting the picture on their front page because it really opened the discussion about the targeting of civilians by the Russian military.”

Addario shows front page featuring one of her photographs during Houghton lecture.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Addario is drawn to documenting the tragedy of war, but she also tries to capture the ways in which life goes on amid the violence as people get married, graduate, and celebrate milestones even in the most dismal situations and moments. She showed pictures of weddings under the Taliban, where people danced, laughed, and celebrated together. “One thing I learned early on in my career is that life goes on, and it’s human nature to want entertainment, to laugh and to be together,” she said.

Since Addario began working as a war photographer, she has not seen an increase in the number of women working in the field. Addario herself was worried about the future of her career after she got married. She was pregnant while working in Gaza covering a prisoner exchange. “After getting pregnant, I continued working,” she said. “I was terrified at the prospect of losing my identity as a war photographer.”

View this post on Instagram

The daughter of Italian American hairdressers, Addario grew up in Westport, Connecticut, where being the youngest of four sisters “prepared” her for her future career. “I think that was probably the best training to cover war,” she said, jokingly. “I was routinely chastised as a young girl and that made me very tough.”In 2015, Addario published a New York Times bestselling memoir, “It’s What I Do,” which chronicles her personal and professional life as a photojournalist.

The lecture was co-sponsored by Houghton Library, the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies, the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies, the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard, the Ukrainian Research Institute, and the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs.

Asked by John Stauffer, professor of English and of African and African American Studies, whether she considers herself an anti-war activist, Addario said her work is to educate people in the brutalities of war.

“I cover certain stories for a reason because I believe that if the public has access to the scenes that I’m seeing, they will have a visceral reaction,” she said. “I’m not activist, but I am certainly a very active journalist, and I cover things that will hopefully open people’s eyes and educate people.”

After the talk ended, Addario went back to work.