Director Mira Nair works on the set of “The Perez Family.”

United Archives GmbH / Alamy Stock Photo

Mira Nair comes full circle with donation of archive

Credits University with starting her in filmmaking as she adds to Schlesinger Library’s widening holdings from underrepresented voices

When Mira Nair ’79 was offered the chance to give her professional archive to Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library, something clicked. “Harvard has changed my life,” said the award-winning director on a recent Zoom call from New York. “There’s no question about it.”

For almost two years the director of “Monsoon Wedding,” “The Namesake,” and “Vanity Fair” filled boxes with papers and other material related to her long career. She had fielded a request from Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences regarding her papers, but Radcliffe’s interest tugged at her heart. “Harvard is the most serious place on earth for these kinds of things,” said Nair, who added she is happy to have her life’s work all in one place.

That work spans more than 30 years and represents the filmmaker’s long and varied career. In addition the collection is a key acquisition for Radcliffe’s Schlesinger Library, representing another important step in its efforts to capture an ever-broader range of women’s voices and perspectives.

“A major South Asian American collection like Mira’s is a wonderful illustration of the breadth of this effort and allows us to show the wide and variegated fabric of what Asian American means,” said Jane Kamensky, the library’s Carl and Lily Pforzheimer Foundation director. “And as a visual intellectual, somebody who has thought so deeply about nation and ethnicity and gender, she was a natural for us.”

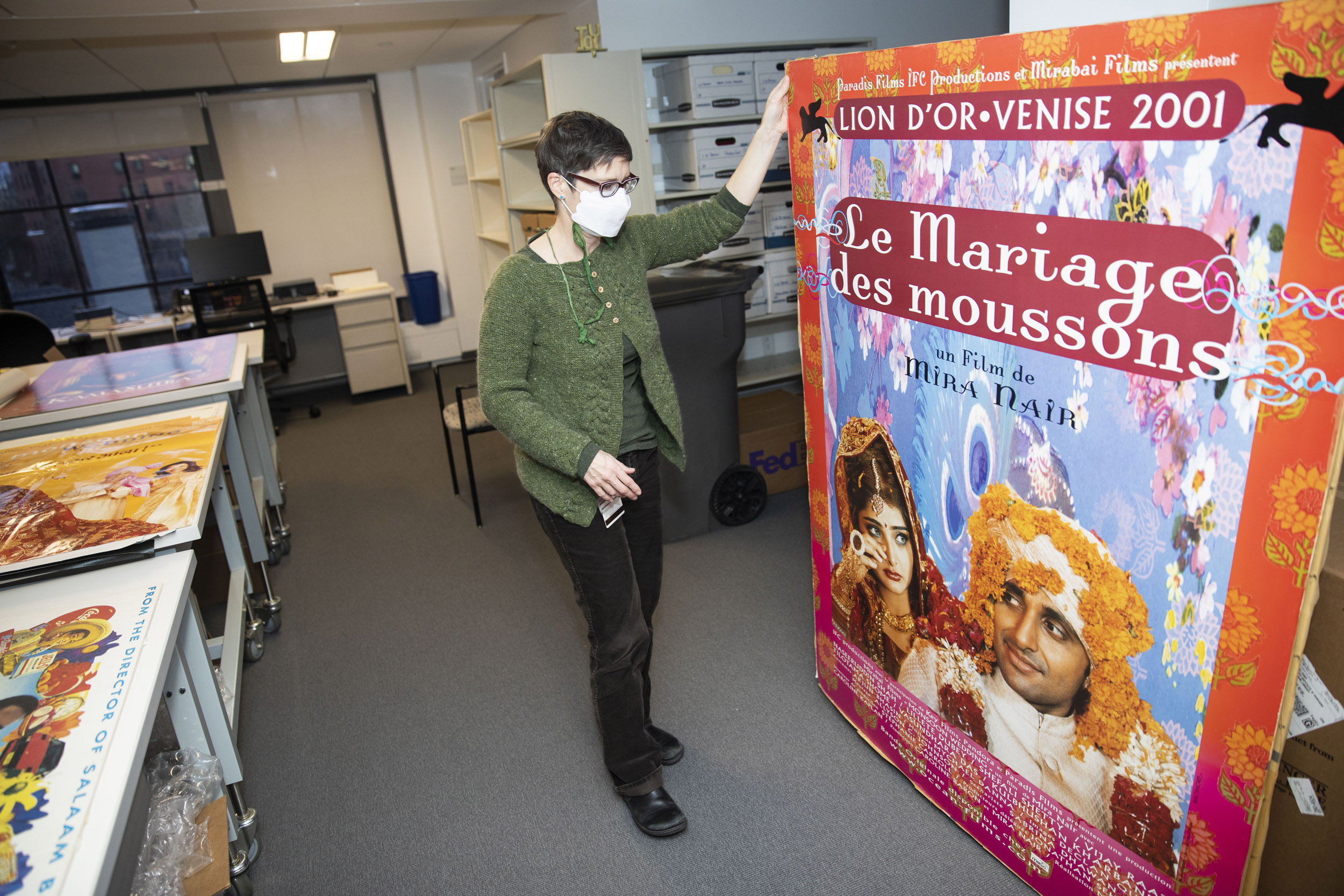

Curator Jenny Gotwals displays some posters from Nair’s collection. In recent months, the filmmaker shipped to the Schlesinger more than 40 cartons packed with film scripts, photographs, correspondence, and journals dating back to 1984.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff Photographer

Over the past several years, aided by a number of advisory and working groups, including one dedicated to Asian American collections, the library has increased its holdings from communities less represented in its archives. Recent acquisitions include the papers of prominent changemakers such as activist and journalist Helen Zia, as well as the collections of lesser-known individuals such as Pin Pin T’an Liu, an immigrant from China who earned a master’s degree in English literature from Radcliffe in 1938 and became the host of a popular U.S. radio show.

The Library was also entrusted over the summer with a number of significant pro-life archival collections by the Sisters of Life, who had cared for the materials for decades at their convent in the Bronx.

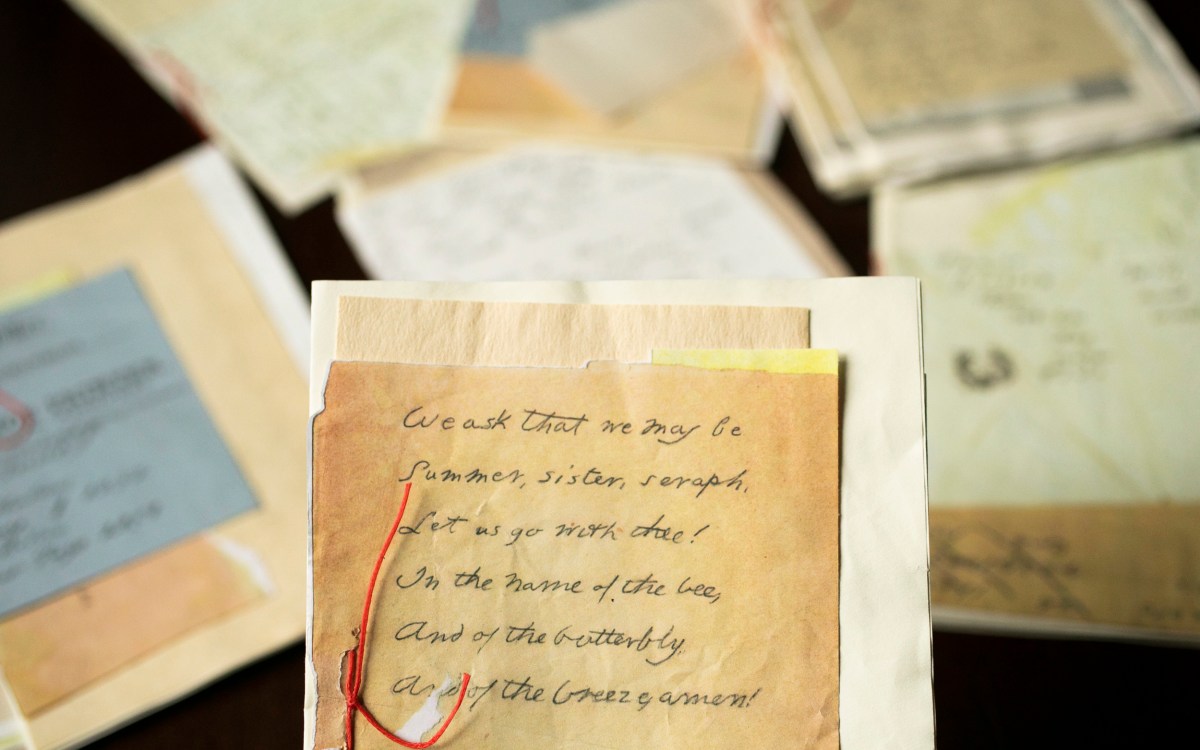

One appreciates the director’s drive and diverse interests after touring a small sampling from the 40 cartons she’s shipped to the Schlesinger in recent months packed with film scripts, photographs, correspondence, and leather-bound journals dating back to 1984 filled with everything from mundane to-do lists to comments on upcoming films. Most of the collection involves her celebrated early works “Salaam Bombay!” (1988) and “Monsoon Wedding” (2001), but it also includes a range of items related to Nair’s most recent projects. A casting sheet with headshots for the upcoming musical “Monsoon Wedding,” set to premiere in 2017 but pushed back due to COVID, includes revealing casting notes such as “great singer, not a good actor,” and a script covered with blue plastic for episode six of her 2020 Netflix series “A Suitable Boy,” featuring Nair’s edits and suggestions outlined in pink.

One fascinating part of the collection involves a film she didn’t make: the fourth “Harry Potter” movie. Nair passed on the chance to direct the installment of the popular franchise to make “The Namesake” (2006), but her notes reveal her due diligence. On a page in a black leather journal from 2004, Nair noted how J.K. Rowling’s young wizard protagonist was “coming into manhood,” and dealing with a range of conflicting emotions including “the stirrings of love, of friendship & loyalty.”

“Precisely because of these heavy ‘themes’ JKR has given us the key to counter or treat these themes by surrounding them w. fantastical visual play,” wrote Nair.

A series of large, glossy posters of her films in French, Japanese, English, and Hindi, and binders filled with press reviews from around the globe highlight her work’s international reach. Letters to potential backers point to the less-glamourous, yet equally important task of film fundraising, and notebooks jammed with photos snapped on the sets of her movies document the action and breaks in the action and feature Nair in candid moments with her cast and crew.

“I’m really happy that the Schlesinger and these great bastions of libraries are now opening their doors to the same internationalism that they had when they opened their doors to me.”

Mira Nair ’79

Nair’s connection to Harvard resulted from a decision she made to head to Cambridge, Massachusetts, instead of Cambridge, England, when it came time for college. She planned to focus on acting at Harvard and performed at the Loeb Theater, but a busy work and course load left her with time for little else.

Then, a Harvard summer course introduced her to photography. “It was wonderful in the sense that it taught me how to see, literally how to frame … but my personality was much more about engagement with people rather than observing them, which is what still photography makes you do,” said Nair. So, she cross-registered for a film class at MIT with cinema verité pioneer Richard Leacock and used her new camera, she recalled, “to engage in life.”

The class inspired her to concentrate in Visual and Environmental Studies at Harvard (today the Department of Art, Film, and Visual studies), where she focused on documentary filmmaking. She called the program her “first education into understanding that cinema was an art form.”

Nair’s senior project, created with the help of a camera lent to her by documentarian and Harvard anthropologist Robert Gardner, examined the lives of locals from the streets of India’s Old Delhi. Her first three films after Harvard followed a similar script, offering viewers a close look at the lives of a newspaper vendor in New York, nightclub strippers, and the unique phenomenon of the laughing clubs of India, gatherings of people who take laughing seriously.

Gradually, she grew weary of documentary. On campus in 2003 to receive the Harvard Arts Medal, the director told Arts First host John Lithgow that her patience with the genre had grown thin: “I was tired of waiting for things to happen,” Nair said. “I wanted to make them happen.”

To this day she considers her Harvard education in cinema verité a formative experience. “It actually is the foundation of my films, even 30–40 years later,” said Nair, “because I understand the electricity of truth.”

That truth was on display in her first feature film, “Salaam Bombay!,” an unflinching look at life in the city’s slums that earned Nair a host of award nominations. She followed it up with the romantic drama “Mississippi Masala,” a love story between a woman from the Indian diaspora and an African American man in the Deep South, starring a young Denzel Washington. In addition to her documentaries, her resume includes 12 feature films, two TV movies, a BBC series, and a long list of accolades and awards.

For many, pulling together such a diverse and detailed archive would be a daunting task. Perhaps even more so for Nair, whose work spans more than three decades, and who divides her time between three continents: North America, England, and Africa. But the option to send her materials to Harvard has been well worth the effort, she said.

“It was such an international space to be at Harvard as an undergraduate. And I’m really happy that the Schlesinger and these great bastions of libraries are now opening their doors to the same internationalism that they had when they opened their doors to me.”