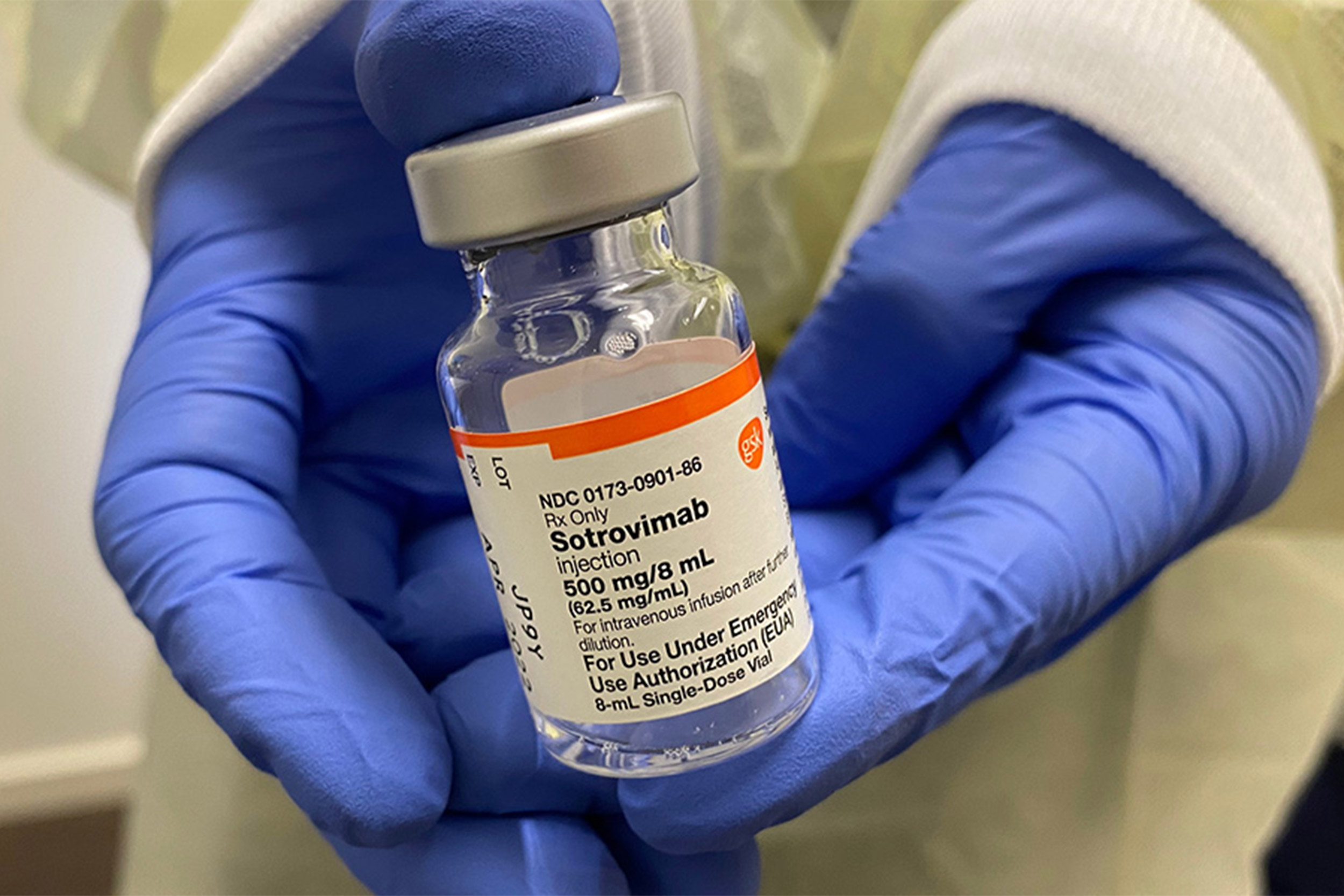

Monoclonal antibodies mimic the immune system’s ability to fight off viruses. As an effective treatment for COVID-19 infections, its distribution was intended to reach the high-risk segment of the population.

Photo: Ice_blue/Shutterstock

The COVID treatment that missed its target

Researchers explain why those at highest risk for severe COVID-19 often least likely to get monoclonal antibodies

People over age 65 at the highest risk for severe COVID-19 have often been the least likely to receive monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) — a highly effective treatment for the disease, according to new research co-authored by researchers from Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The analysis was published online Feb. 4 in JAMA.

“Monoclonal antibodies should first go to patients at the highest risk of death from COVID-19, but the opposite happened — the healthiest patients were the most likely to get treatment. Unfortunately, our federal and state system for distributing these drugs has failed our most vulnerable patients,” said Michael Barnett, assistant professor of health policy and management at Harvard Chan School and lead author of the study.

Monoclonal antibodies are very effective at treating mild to moderate COVID-19 infection among non-hospitalized patients. But during the pandemic, mAbs have been in short supply. Federal guidelines prioritize patients at higher risk of being hospitalized or dying from COVID-19, including older people and those with chronic conditions.

The researchers wanted to learn how the limited supply of mAb therapy was allocated to patients at highest risk for severe disease. They looked at data from more than 1.9 million Medicare beneficiaries who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 between November 2020 and August 2021, and compared rates of receiving mAbs by age, sex, race and ethnicity, region, and number of chronic conditions.

“Monoclonal antibodies should first go to patients at the highest risk of death from COVID-19, but the opposite happened — the healthiest patients were the most likely to get treatment.”

Michael Barnett, Harvard Chan School

They found that, among Medicare beneficiaries who weren’t hospitalized or who didn’t pass away within seven days of their diagnosis, only 7.2 percent received mAb therapy. The likelihood of receiving mAbs was higher among those with fewer chronic conditions — 23.2 percent of those with no chronic conditions received mAbs, versus 6.3 percent, 6.0 percent, and 4.7 percent of those with 1-3, 4-5, and 6 or more chronic conditions, respectively. The researchers also found that Black people were less likely to receive mAbs than whites — 6.2 percent versus 7.4 percent.

In addition, there were significant differences among states when it came to mAb treatment. For example, Rhode Island and Louisiana administered mAbs to the highest proportion of non-hospitalized patients with COVID-19 (24.9 percent and 21.2 percent), while Alaska and Washington administered the lowest proportion (1.1 percent and 0.7 percent ). Southern states had the highest rates of mAb therapy (10.6 percent of beneficiaries), while states in the West had the lowest rates (2.9 percent).

Speculating as to why mAb therapy often failed to reach the highest-risk COVID-19 patients, the researchers said it’s possible that higher-risk patients may have had difficulty navigating the multiple steps needed to receive mAbs, from receiving a timely diagnosis to referral and scheduling an infusion within 10 days. As for differences among states, they suggested that mAb supply may have been low or less used by clinicians in some regions of the U.S.

“We need new approaches to prevent these inequities from happening again with newer treatments on the horizon,” said Barnett.

Other Harvard Chan School co-authors included Ellen Meara, Arnold Epstein, and E. John Orav.

Funding for the study came from the National Institute on Aging (grant K23 AG058806) and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (award U19 HS024075).