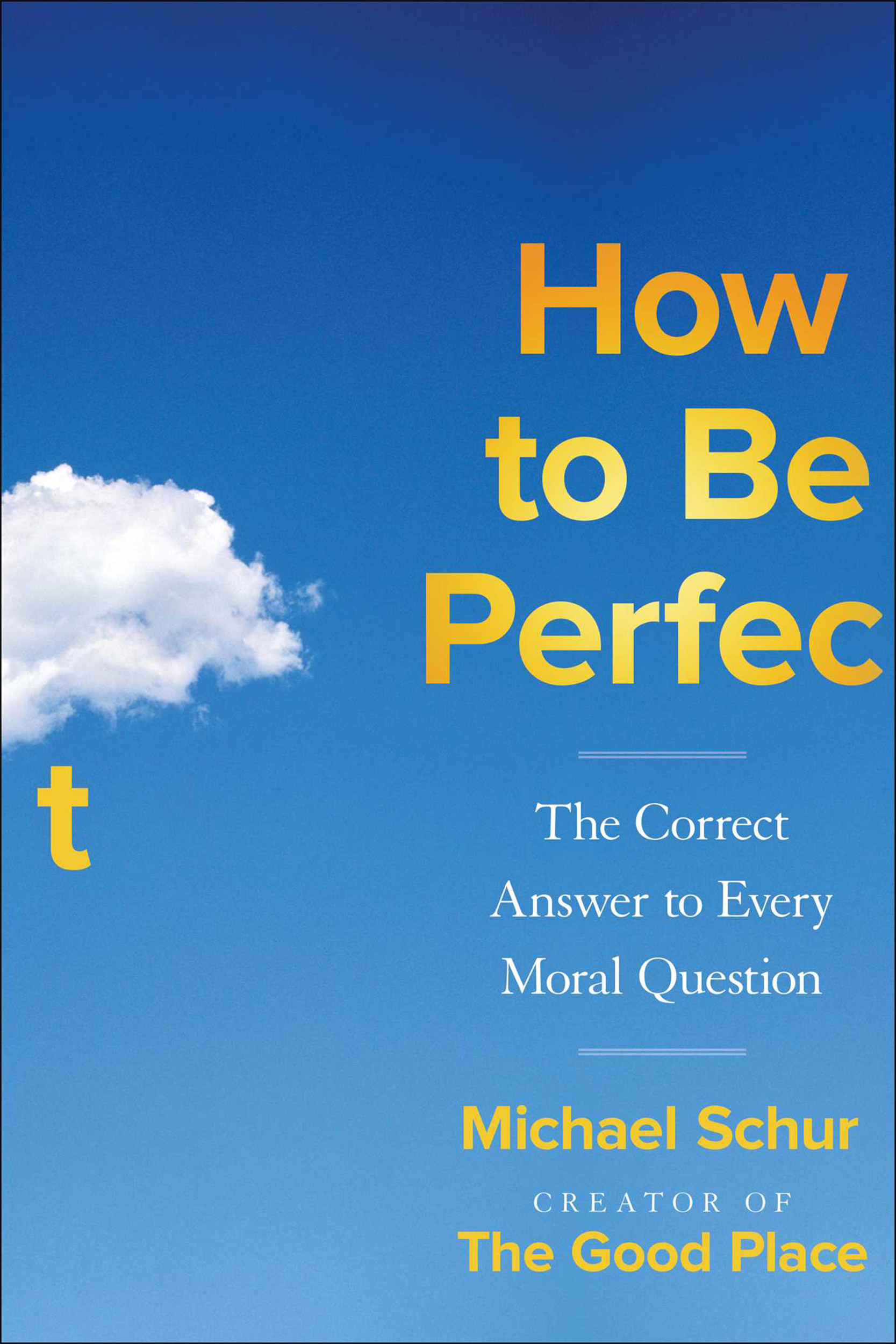

How to be perfect

Creator of hit TV comedy ‘The Good Place’ Michael Schur discusses his new book on moral philosophy

“Honestly, it was hard not to make the whole book about the pandemic, because what was required of us was immediately evident. It was fairly minimal, and yet it was incredibly controversial,” says author Michael Schur ’97.

Photo by Marlene Holston

Michael Schur was getting ready to create “The Good Place,” his hit TV comedy about the afterlife and what it means to be a good person, and it occurred to him that to do it right he had to “actually know what I was talking about.” So, the 1997 College grad did a deep dive into seminal works of moral philosophy and talked to professors “who could help me learn and understand what it was all about.” Besides the show, what he learned also inspired his new book “How to Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question.” The Gazette spoke with Schur about his interest in understanding, and helping others understand, how to be better.

Q&A

Michael Schur

GAZETTE: Did you think you might want to write a book on the topic of moral philosophy one day?

SCHUR: I’d done all this reading, and I’d had all these discussions with all these smart people, and I had come to some kind of conversational understanding of the topic, and it felt like a blessing in some weird way that I had this new vocabulary that I could use to discuss my own personal failures. I found that very comforting. Then I thought, “What if I could take what I’ve learned and translate it into a conversational text that others might get some use out of?” I’m a comedy writer — comedy writing is not the main strength of most philosophers — and I thought I could maybe be a bridge between this thorny stuff and the people who might not otherwise be inclined to engage with it.

GAZETTE: In the book you use extensive humorous footnotes. Why did you make that choice?

SCHUR: If you are writing dialogue for a TV show, when somebody says something, you can cut to somebody else who makes a joke or says something funny. The closest you can get to replicating that comedic rhythm in prose is a footnote because you are literally drawing the reader’s eye down to a different spot and then doing something that punctuates with a joke whatever it is that you’ve set up in the text. One of the reasons David Foster Wallace so captured my personal imagination was because his footnotes made reading his books feel like I was actively participating in the way that the prose unfolded. Ever since I read “Infinite Jest” in 1996, I’ve loved footnotes. And anytime I’ve written anything in prose, I’ve used footnotes and tried to use them in the same way he did.

GAZETTE: Can your book help us think through how people have responded to the pandemic, and objections to mask mandates and vaccines?

SCHUR: Honestly, it was hard not to make the whole book about the pandemic, because what was required of us was immediately evident. It was fairly minimal, and yet it was incredibly controversial. I found it very dispiriting. It’s not hard to understand why wearing a mask and social distancing and getting a vaccine, if you can, are important. And yet a third of this country dug in their heels and said, “I’ll never do that for any reason.”

And there’s not one simple explanation for that. There’s a media apparatus that makes money off of divisiveness so it’s not shocking that’s what happened. But it is still sad to me that it’s so effective, that people are so susceptible to it, because it’s not controversial to say that you owe certain things to other people, that we have an interconnectedness and an inter-reliance that is vital for the survival and flourishing of the community that we live in. And yet, we still have people saying, “My unfettered right to do whatever I want, whenever I want, outweighs the entire value of any kind of collective public health,” which is just shocking. I didn’t think that it was possible that so many people would be so selfish.

GAZETTE: What do you hope people take from the book?

SCHUR: I think my book is trying to argue that none of these approaches to being a good person, whether it’s Aristotle, or Kant, or utilitarianism, is the only thing you need. You really need to understand all of them, because at different moments in your life, they’ll come in handy in different ways.

GAZETTE: Do you think it might be hard for some people to take advice from a core group of philosophers you cite, white men of privilege, whom you also refer to as “snobs”?

SCHUR: It’s a sad fact of history that white dudes were the only people who got to write philosophy forever. Women, people of color, and so many others just weren’t allowed in universities for a really long time. So, what we’re left with is a bunch of theories that have an enormous amount of merit and good things about them, that just all happen to come from essentially one group of people. There’s nothing we can do about that. We can’t go back in time.

I tried very hard in the book to welcome into the tent a lot of people who were traditionally marginalized or ignored. I think it’s interesting that the trolley problem, maybe the most famous philosophical thought experiment in history, was written by Philippa Foot in 1967. Most of the discussion of that problem was written by women: Elizabeth Anscombe and Judith Jarvis Thomson and others. If you’ve followed the development of the trolley problem in the last 50 years, women are certainly leading the way.

And then there are theories that people have largely ignored or dismissed as not important. Like Ubuntu, which is a Southern African philosophy, which I write about. There’s also a lot of East Asian philosophy that, strictly speaking, one wouldn’t label ethical philosophy. It’s more like the kind of societal philosophy embraced by people such as Lao Tzu.

And finding other voices is not hard. A lot of the active contemporary philosophers whom I personally just find the most interesting are not white dudes. The paper Susan Wolf wrote on moral saints is one of my favorite things I’ve ever read in the field. It’s a really beautiful paper, and it’s unlike a lot of philosophy I’ve read. It’s eminently readable, and it’s also just really elegant. So, it was important to me to have diverse voices, but also it just ended up being what happened because I personally found those people’s writings more clear and more interesting than a lot of the other stuff I read.