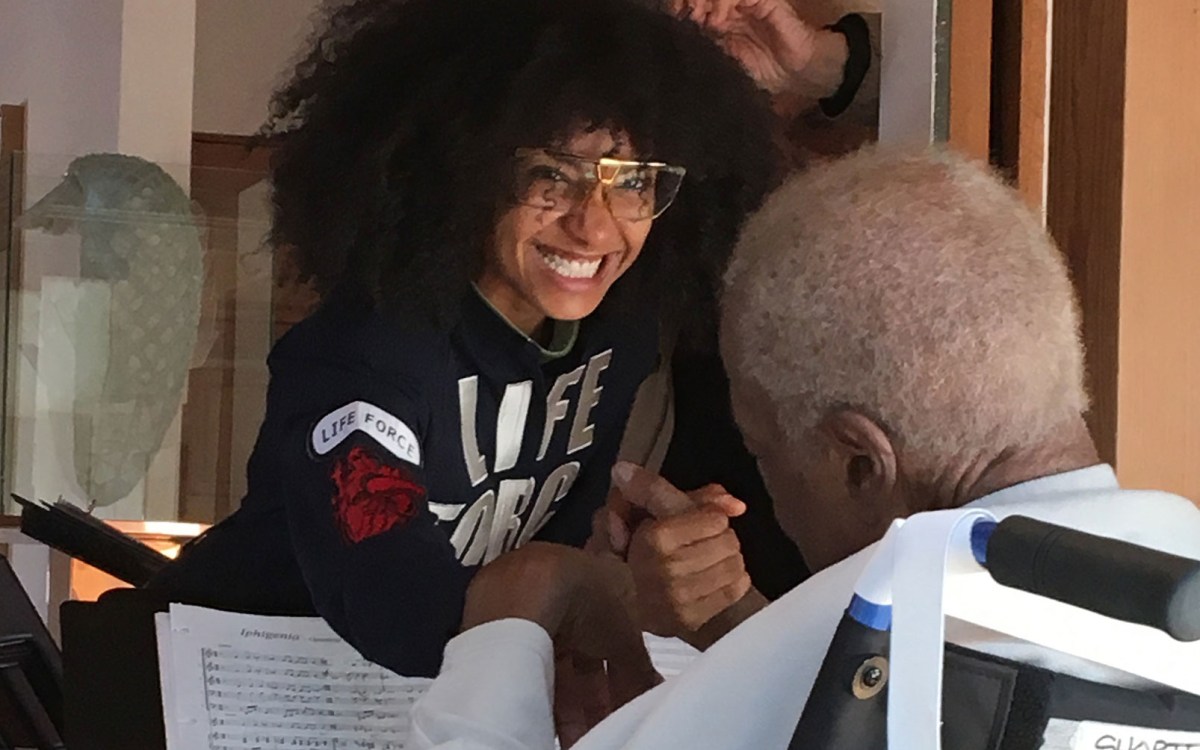

Stephen Sondheim and John Weidman in Sondheim’s living room in 2008 during a party for the cast of “Road Show.”

Photo courtesy of John Weidman

The Sondheim he remembers: genius, friend, board game geek

Harvard grad collaborated with giant of musical theater, ‘a warm, generous, open spirit,’ on three shows

The composer and lyricist Stephen Sondheim, who transformed American musical theater in the 20th century, died Nov. 26 at the age of 91. The Gazette spoke with John Weidman ’68, who collaborated with Sondheim on “Pacific Overtures,” “Assassins,” and “Road Show,” about their working relationship and decades-long friendship. The interview has been edited for clarity and length.

On his first encounter with Sondheim’s work

My first exposure to Steve’s work was the movie version of “West Side Story.” I think I saw it two or three times. I loved it, but I was not looking at it as somebody who might one day work in the theater. I was just a high school kid sitting in the audience, mostly being knocked out by [Leonard] Bernstein’s music and [Jerome] Robbins’ choreography — although I think I could recite the lyrics to “Gee, Officer Krupke,” which Steve wrote, the first time I walked out of the theater. I think my first real, conscious awareness of the extraordinary work that Steve was doing in conjunction with director and producer Hal Prince came when I saw “Company,” and to an even greater degree when I saw “Follies.” I remember going with my girlfriend to see “Follies” at the Winter Garden Theatre. And I just thought that what the two of them were putting up on stage was astonishing and that the collection of songs was extraordinary. In 1998, my wife, Lila, and I, along with James Lapine and his wife, Sarah, went to the Paper Mill Playhouse to see a revival of “Follies.” As we came out of the theater, I remember Lapine chuckled, turned to me, and said, “You know, if you wrote something like that, why would you bother to write anything else?” So, I think “Follies” was the first time I really tuned in to the genius of what Steve was creating. The four songs which constitute the follies section at the end of the show still seem to me to be one of the greatest sequences ever written for the musical theater.

On Hal Prince introducing him to Sondheim to collaborate on “Pacific Overtures,” which evolved into a musical after Weidman wrote the play while a law student at Yale

Hal called me up and he said his designer, Boris Aronson, couldn’t figure out how to design the play that I’d written. To Hal that meant there was probably a problem with the play, and he thought it needed to be a musical. He told me he was going to send it to Steve to see what he thought. As I recall, Steve’s first reaction was, “This is interesting. I could imagine it having music, but it doesn’t feel like a musical to me.” But Hal was, if nothing else, persistent. He convinced Steve that there was a show there. And so, my first face-to-face encounter with Steve was a meeting in Hal’s office in which the three of us were getting together to talk about this Broadway show that we were going to do together. I’d been living on one side of a line in which I was a Stephen Sondheim fan and all of sudden I had stepped across the line, and I was now going to become his collaborator. This was not about a mentorship relationship. We were structural equals in the sense that Steve’s job was to write the score and my job was to write the book. And Steve, of course, had a trail of seven or eight consequential, form-bending shows behind him, and I was just a guy who was trying to find a way not to be a lawyer.

On collaborating with Sondheim

Among other things, Steve was just very open to what interested him regardless of where it was coming from or where it was going. When we were working on “Pacific Overtures,” I remember there was one event in the second act that had yet to be written. It was a scene we all assumed would become a song. The idea was that I would go home and write a series of letters that described the key evolution of one of the main characters in the show, and Steve would inhale the letters and then exhale them as a song. What happened instead was I brought the letters in, Steve read them, really liked them, and decided to write the song in between the letters. That resulted in what I think is honestly one of his greatest songs, “Bowler Hat.” And it’s always pleased me that you hear my voice on its own, and then Steve’s voice on its own, alternating with each other in order to achieve the full effect of the number. A hugely satisfying collaborative experience.

I feel very lucky to have been part of a small club of people who got to participate as partners in Steve’s creative process. Once he and I discovered that we meshed, that process frequently involved sitting around, usually in the study on the second floor of his townhouse on 49th Street, just talking through a variety of ideas, seeing where the ideas led us, and exploring any new ideas that bubbled up along the way. Given Steve’s eminence, people probably assume there was a kind of senior partner/junior partner quality to these conversations, but they weren’t like that. For instance, when I think back on “Assassins,” we started with the germ of an idea — in fact we weren’t even really sure what the idea was. We met once a week, and talked around the idea from a variety of different perspectives until we realized why we were interested in what we seemed to be interested in. And those conversations continued for months until we had arrived at a point where we had a shared sense of the show we wanted to write. At that point, Steve went away to write the opening number and I went away to write the first draft of the book. The quality of those conversations was exhilarating. Whenever I left his townhouse and hit the sidewalk to head home, my mind would be buzzing with everything that we had talked about.

On his friendship with Sondheim

Our friendship began when we first met to work on “Pacific Overtures” and continued right up until his death. We became good, close friends. We would go to the theater together. We’d have dinner together. After “Pacific Overtures,” which opened in 1976, there was about a 10-year period where I really wasn’t working in theater much. I was one of the early editors at the National Lampoon, so I was doing a lot of Lampoon work. After “Animal House” came out, I wrote three or four screenplays for different studios because I’d been a Lampoon editor, and they were all hoping lightning would strike twice. During that time, even though we weren’t working together, Steve and I would get together frequently. He was the one who did most of the entertaining. He had a spectacular tradition called games nights. Lila and I and another couple would go over to Steve’s. Everybody would have drinks, we’d have dinner, and then some sort of exotic board game, which was part of Steve’s enormous collection, would become the entertainment for the rest of the evening. Those nights were delightful. I miss them. Everyone knows that Steve was clever and funny, but as a friend he was much, much more than that.

“Whenever I left his townhouse and hit the sidewalk to head home, my mind would be buzzing with everything that we had talked about.”

On Sondheim’s influence

You look at his body of work, at the variety of subjects which he approached, and at the quality of the work across the board — whether he was writing about marriage in “Company,” or about presidential assassinations in “Assassins,” or about fairytale characters in “Into the Woods.” He had a fierce intelligence, and he was fearless, and I think one of the things that he pioneered was the notion that if you had an idea for something you wanted to write about, you should just go ahead and write it. The variety of his shows seems to me to reflect that. People can describe the work as being pioneering in the sense that it was kind of unconventional. I just think he was a brilliant artist and that that brilliance is reflected in the unique quality of what he produced.

On Sondheim, the mentor

My daughter went to Hunter College High School in New York, and she came home one day and asked if I could get Steve to talk to the school’s drama club because they were doing “West Side Story.” I called Steve, who said sure. We went over to the school together, and it turns out the guy who had asked my daughter to ask me about Steve was the musical’s director, Lin-Manuel Miranda. That was, I believe, the first time Lin-Manuel and Steve were in the same room at the same time. It would not be the last.

It was such a pleasure to sit there and watch Steve engage with these kids and answer their questions about his lyrics for the show, because he loved to talk to students. One of them asked about the famous introductory dance section and that was when I found out that Steve had actually written a whole set of lyrics for the prologue to “West Side Story.” He told them the Jets had a clubhouse, and that the character Riff had a horn, that’s why he was called Riff. His willingness to engage with the students and to share with them those details reflected a hugely generous aspect of who he was. I think he had gotten so much from his relationship with Oscar Hammerstein, who was willing to take the time to analyze Steve’s work, talk to him about it, be frank when he was critical of it. I think he really enjoyed passing that on. He did that a lot. He had a warm, generous, open spirit, which I am going to miss.