‘The steam and chatter of typewriters’

Students from the MFA Writers’ Program at UMass Boston visit the Woodberry Poetry Room to use John Ashbery’s typewriter.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

John Ashbery’s became an integral part of the poet’s writing process, and now has home in Woodberry Poetry Room

John Ashbery dove head-first into poetry after arriving at Harvard in 1945. His biographer Karin Roffman described him as “a constant presence” in the Woodberry Poetry Room (formerly at Widener Library until 1949), where he would discover the works of W. H. Auden, the eventual subject of his thesis.

As a student, Ashbery attended readings of the works of Auden, Morris Gray, and Marianne Moore, explored local bookshops, and befriended fellow poets, including Frank O’Hara, Kenneth Koch, and V.R. Lang. “The great modernist poets were the poets he was imbibing,” Roffman said in an interview with the Gazette. “He was really thinking about the given canon that he was getting in classes at Harvard and then the personal canon he was making for himself.”

The experiences were formative for Ashbery, who died in 2017 at the age of 90, and Harvard has become the center of study on the celebrated poet. The University acquired his papers over a period of years and his reading library — donated by his husband, David Kermani — in 2018. Last month Ashbery’s typewriter, also a gift from Kermani, was installed in the Woodberry Poetry Room at Lamont Library, which will host an event, “Lunch Poems: Adventures with John Ashbery’s Typewriter,” featuring Roffman and Ashbery’s former assistant and editor Emily Skillings, on Wednesday, Nov. 17.

Much of Ashbery’s poetry throughout his career, was written on typewriters, but his love affair with the machines started after graduation. The budding poet didn’t have access to one during his studies likely due to the expense — he even got his thesis typed by someone else who did have one.

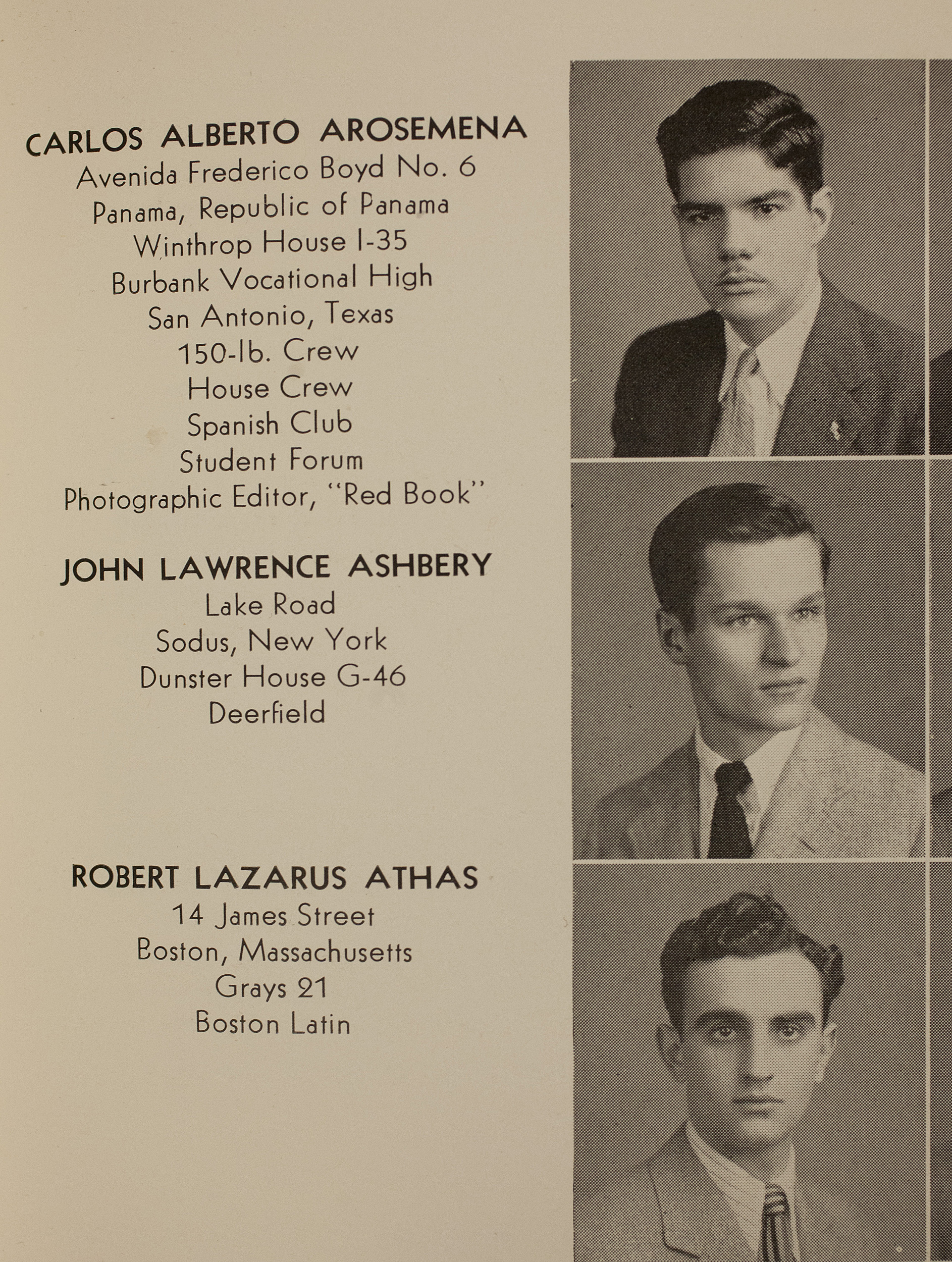

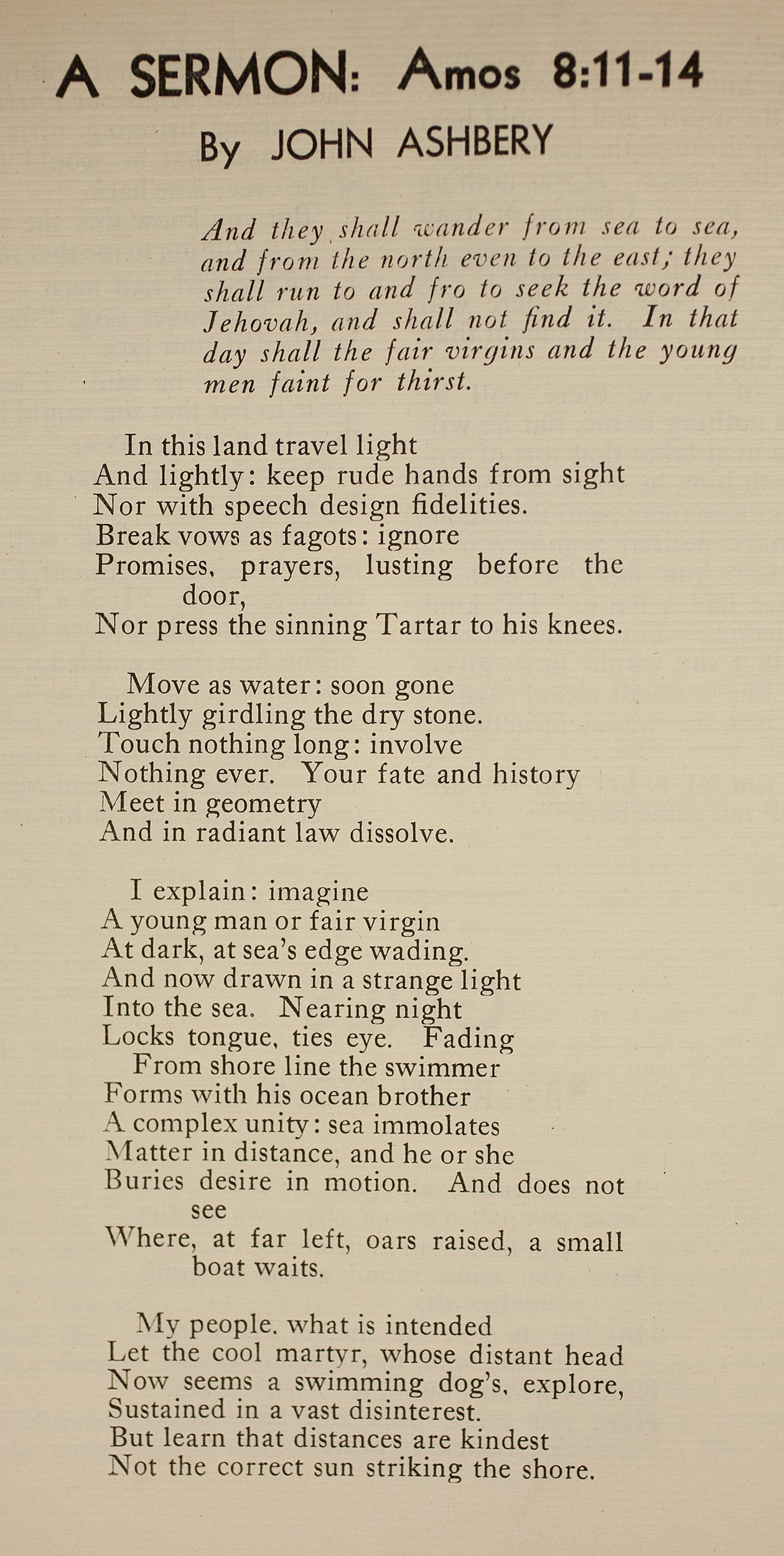

Class portrait and information on John Ashbery from the freshmen register during his days at Harvard. “A Sermon: Amos 8:11-14” by John Ashbery.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

After graduation, he worked in New York writing advertising copy for Oxford University Press and McGraw-Hill. He kept a Royal typewriter on his desk, the brand he would prefer for the rest of his life. Through this job, he became a fluent and adept typist, and though he still didn’t have a typewriter in his home, he would go to his office at McGraw-Hill to type poems. During this time he wrote his first book, “Some Trees,” published in 1956, based on a poem he wrote while at Harvard.

Ashbery left New York for France on a Fulbright Fellowship, and there wrote “The Skaters” in 1963. According to Roffman, this was a poem that “he really felt needed to be typed.” Ashbery could write faster on a typewriter than by hand at that point, and he thought the poem — which would eventually total 739 lines — was getting away from him.

“The poem has really, really long lines, and he needed to get to the end of the line before he forgot it,” Roffman explained. “He was a really quick thinker, so one can imagine that having a quick machine would be helpful.”

Ashbery said in a 1983 Paris Review interview that after finishing “The Skaters” he did all of his writing on the typewriter. It became such an integral part his work, in fact, that his poem “Idaho,” which appears in his 1962 collection “The Tennis Court Oath,” includes long strands of typewriter symbols.

His connection to the machine extended to even the physical experience of using it. In “Paradoxes and Oxymorons,” he wrote: “And before you know / It gets lost in the steam and chatter of typewriters.”

John Ashbery reads his poem “Paradoxes and Oxymorons” in a recording for Radio Helicon, June 19, 1988. His typewriter is pictured in his New York City apartment. Photo by Danniel Schoonebeek

transcript

Transcript:

This poem is concerned with language on a very plain level.

Look at it talking to you. You look out a window

Or pretend to fidget. You have it but you don’t have it.

You miss it, it misses you. You miss each other.

The poem is sad because it wants to be yours, and cannot.

What’s a plain level? It is that and other things,

Bringing a system of them into play. Play?

Well, actually, yes, but I consider play to be

A deeper outside thing, a dreamed role-pattern,

As in the division of grace these long August days

Without proof. Open-ended. And before you know

It gets lost in the steam and chatter of typewriters.

It has been played once more. I think you exist only

To tease me into doing it, on your level, and then you aren’t there

Or have adopted a different attitude. And the poem

Has set me softly down beside you. The poem is you.

Christina Davis, curator of the Woodberry Poetry Room, hopes visitors will be able to make those same connections during their sessions with the typewriter.

“The experience that visitors have with Ashbery’s typewriter is at once mechanical and metaphysical,” she said. “I had thought the most meaningful part was going to be the connection to this one individual, but it has been so much more expansive than that, seeming to connect them to the collective unconscious of the 20th century.”

There have been two types of visitors so far, Davis noted: those raised before the advent of computers who are familiar with typewriters, and those who had never used a typewriter before visiting the room.

Suzanne Mercury, a Boston-based poet, described her visit as “almost mystical.” During her session, she chose to write some poems of her own and a thank-you note to Ashbery himself.

“What I felt most was the spirit of Ashbery’s warmth and generosity as I sat there and typed away on my poems. I was so grateful because it all felt so intimate and immediate,” she said.

Benjamin Wright and Lizzy Gagne from the MFA Writers’ Program at UMass Boston use the typewriter.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

John Ashbery (center) at a 2002 reading at Norton Lecture Hall.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard file photo

Mercury, who is familiar with typewriters and their use, quickly got back into the flow of using one.

“The experience returned me to the physicality of writing, which I certainly feel when I write longhand or do my visual and haptic poetry experiments, but which is completely lost when I use a computer,” she said.

Sammy Jo Hester, a Neiman fellow and sports photo editor at the LA Times, experienced using a typewriter for the very first time during her session. This was especially significant to her as a fan of Ashbery’s work. She first discovered poetry in childhood and returned to it eight years ago to help her process the challenges of living with a heart condition.

“I don’t believe in a magic typewriter that turns your writing into greatness any more than I believe in a magic pan that turns you into a chef. But I do believe in understanding the tactility of touching a piece of history that, in some small way, touched other people’s souls,” Hester said. “John’s typewriter is just that and I am very grateful for the experience.”

The ability to interact with an artifact such as this is rare, Davis added.

“Usually when you go to an archive you’re encountering the work of art, but in this scenario visitors are having an intimate and interactive experience with the means of creation itself,” she said. “Each person uses the hour in a very distinct way and each future visit will likely widen those possibilities.”

Registration for the Nov. 17 event is offered to a small in-person audience in the room, and the event will be live streamed via Zoom.