John Harvard gets a facelift

Photos by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

The iconic statue appears bronzed, rested, and refreshed after time with a team of specialists

It goes without saying that regular maintenance is key to the good looks of the Old Yard’s most popular resident who is nearing 140 and has endured much at the hands of visitors and vandals.

The iconic John Harvard Statue, modeled after a student from the 19th century (not the 17th-century English minister and generous College benefactor, John Harvard), receives occasional washings by Harvard’s Landscape Services team, but last month he had a kind of statuary spa treatment.

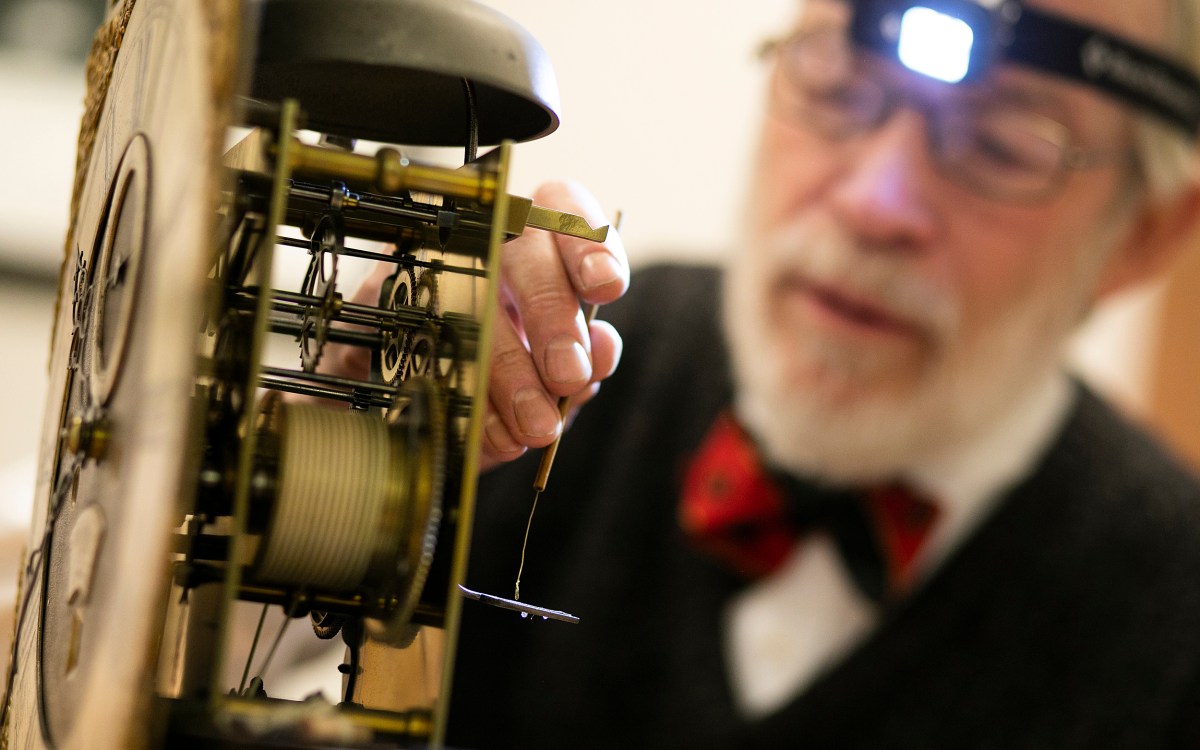

For several days in July and August, a team specializing in the restoration of public monuments carefully performed their magic behind a screen of green scrim and chain-link fencing in front of University Hall. Armed with paint brushes, soft cloths, power washers, and a leaf blower (for drying), they restored the original color and shine to the 1884 statue by the artist Daniel Chester French, famous for his later sculpture of a seated Abraham Lincoln on Washington’s National Mall.

“We think of the John Harvard Statue as being a kind of stable, forever monument, but this bronze is actually a delicate work of art,” said Angela Chang, a specialist in the conservation of objects and sculpture at the Harvard Art Museums. “In the museum, we are able to really care for work like this much differently than something out here.”

Robert Shure, head of the local sculpture design firm Skylight Studios in Woburn, Massachusetts, led the gentle rehabilitation effort with guidance from Chang, assistant director of the museums’ Straus Center for Conservation and Technical Studies. The famous statue is officially part of the University Portrait Collection, a group of paintings and sculptures dispersed around campus and cared for by the Harvard Art Museums.

Luciano Caruso of Skylight Studios gives John Harvard a refreshing shower.

Video by Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

In the spring, passersby might have spotted tiny bits of glitter stuck on with glue — the stubborn remains of a prank — near his collar. Those specks are now gone, as is the faint graffiti carved into the bronze near the base of his chair where two books lie almost hidden by the sitter’s sweeping robes. Then there are those famous, fancy shoes; the left one is a particular favorite of sightseers who have rubbed off the rich brown patina from the toe in the hopes of good luck. Thanks to Shure, the shoe has been returned to its original hue.

But it seems neither tricksters nor tourists can compare to Mother Nature. Unsurprisingly, blazing sun and acid rain can wreak havoc on an open-air sculpture.

“Any bronze in an outdoor environment in New England needs maintenance,” said Shure, an accomplished sculptor and master conservator whose shop recently restored the massive bronze Robert Gould Shaw and Massachusetts 54th Regiment Memorial situated across from the Massachusetts State House in Boston. “What happens is the acid rain actually will etch the surface of the bronze so that you’ll lose a lot of the detail.”

To protect John Harvard from the elements, Shure and his team stripped off an earlier protective lacquer coating that had begun to deteriorate, washed the statue, and restored its original brown patina. They then reapplied a protective lacquer finish, and a final layer of wax. They also cleaned the work’s granite base, along with the two bronze seals on either side representing Harvard College and Emmanuel College, where Harvard earned his B.A. in 1632 and M.A. in 1635, and repainted the inscription on the front of the stone’s base. Originally gilded when the sculpture was dedicated in 1884, the choice to use gold paint on the engraving was a practical one, said Chang. “Although it appears less brilliant than gold leaf, we will be able to touch up the lettering more easily.”

The engraving gets a touch-up.

Today the work looks as it would have when it was first dedicated, thanks in large part to Chang and her museum colleagues who, after careful deliberation, opted to have Shure restore and reintegrate the worn brown patina, shoes and all. “It was a curatorial decision to bring the golden areas more into line with the rest of the piece,” said Chang. “We wanted to present the work the way the artist originally intended.”

But while it’s historically accurate, the effect is also likely fleeting. No touch-up can compete with the eager hands that will soon turn the foot from brown back to gold, said Shure. “It’s just polished by fingerprints … but that’s some of the charisma of the piece, because you are rubbing it for good luck.”

And rub, or pose, visitors will. On a recent summer morning, intrepid travelers from afar eager for a snapshot tried to sneak through the small opening between the fencing and the wall of University Hall. Others climbed nearby steps and worried aloud, “How are we supposed to take our selfies?” Earlier in the year as Chang was completing survey work on the statue, one particularly bold tourist asked her to come down from her ladder and move aside so they could get a clean shot.

Chang gets it.

“There are so few places for the public to touch and connect with the University,” she said. “The John Harvard Statue is so important in that way, as tangible symbol, and that’s what makes preserving the object as an artwork so important.”