Giving Carrie Mae Weems her due

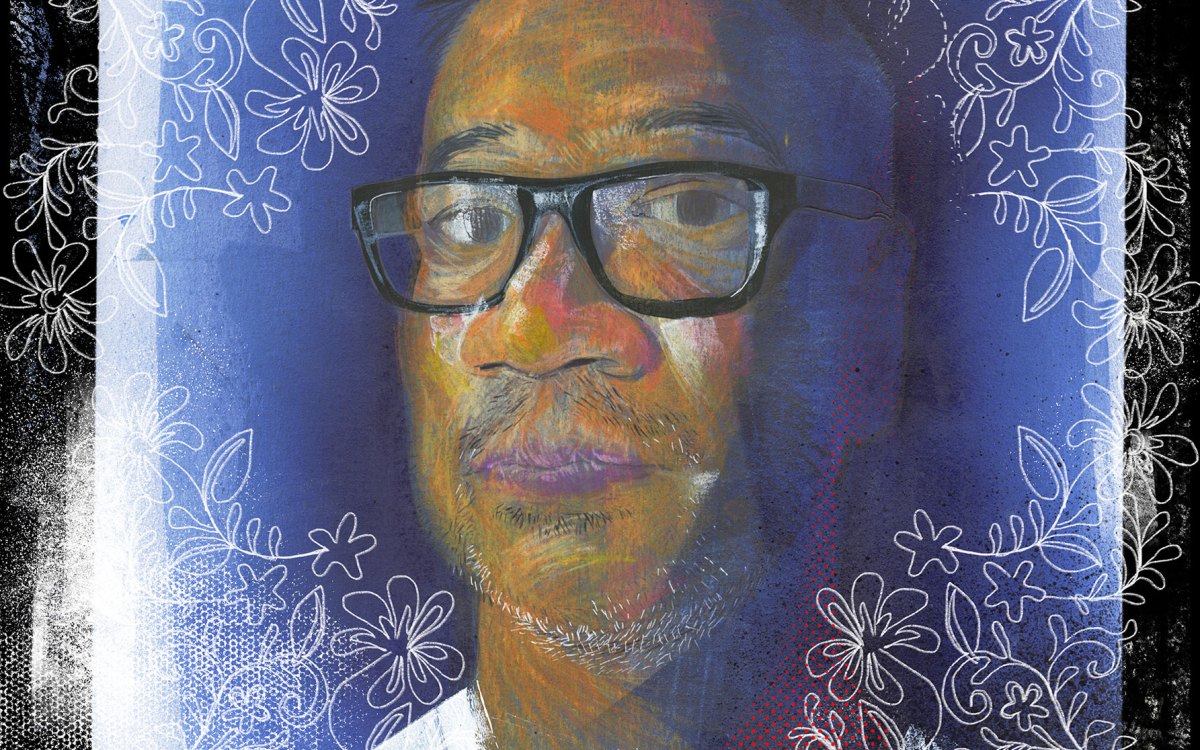

“Mourning,” from the Constructing History series, 2008.

© Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, New York

New volume fills gap in scholarship on work of celebrated Black photographer

The American artist Carrie Mae Weems for more than 30 years has been creating works largely centered on the lives of women, working-class people, and Black people. She is perhaps best known for her photographic projects, including “The Kitchen Table Series” featuring intimate moments around a kitchen table, and “From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried,” based on daguerreotypes depicting enslaved people.

But when Sarah Elizabeth Lewis, an associate professor of History of Art and Architecture and African and African American Studies, and Christine Garnier, a doctoral candidate, started compiling material for a new edited volume on Weems’ work, they realized there was a lack of existing scholarship, which “typifies a pattern, when it comes to many artists of color, but specifically Black artists,” said Lewis.

“Work is often over-exhibited (or instrumentally displayed) and undertheorized,” she said.

The Gazette spoke to Lewis about mending this gap in scholarship by bringing together interviews, criticism, and theoretical analysis of Weems’ work from scholars and artists, including Weems herself.

Q&A

Sarah Elizabeth Lewis

Gazette: How did you want to shape the book “October Files: Carrie Mae Weems,” given the gap in scholarship on Weems?

Lewis: It is no exaggeration to say that Carrie Mae Weems, an extraordinary artist and thinker, is one of the most prodigious artists of our time. I am so grateful that my colleagues Benjamin Buchloh [Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Modern Art] and Carrie Lambert-Beatty [Professor of HAA and Art, Film, and Visual Studies] kindly invited me to edit this volume of scholarship on the work of Weems, and because of who Carrie is we all thought it would be a straightforward process. Yet when I examined the history of criticism and scholarship on her practice, I was stunned. The research showed that the scholarship on Carrie Mae Weems early on is represented by the work of two individuals mainly — bell hooks and artist Coco Fusco — followed by a break in substantive scholarship on her, specifically, for nearly 15 years, capped by a flurry of wonderful essays by scholars. Within the gap, the most thorough works are interviews with Carrie herself. Knowing how widely celebrated she is and has been, the pattern was hard to accept. The discovery of this improbable desert of scholarship—and what it says about the changes in the discipline of art history — is my most vivid memory about putting this book together.

The problem here is not just having Black art become celebrated, yet not fully documented or theorized — creating these glaring asymmetries between level acclaim and substantive discourse surrounding the artist’s work — but this lack of scholarship also exacerbates the structural inequities faced by artists of color, and by Black artists in particular. Carrie Mae Weems reflected on these gaps in her conversation with Thelma Golden and I for this volume. As she put it: “This is not something that just happens with me as a woman. It has happened consistently with African American artistic practice and I think it’s one of the downfalls of the field to not really take it on.” So, this volume takes it on and shaped the themes of the book. It became a collective pean to this irreplaceable figure, and covers her projects, but is also an analysis of the changes in the discipline of art history itself.

“A Single Waltz in Time,” from The Louisiana Project, 2003.

©Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, New York

Gazette: Why did you want to include different forms of analysis (interviews, essays, etc.) and how did this diversity of analysis contribute to your understanding of Weems’ work and voice?

Lewis: Great question. There are two reasons. The volume includes articles, essays, but also three interviews with Carrie — including with Dawoud Bey, Kimberly Drew, and Thelma Golden and I — because Carrie’s voice is perhaps her most prodigious instrument. She is in vertiginous pursuit of the depths to seek, you could say, the ground of history. The questions she asks are crucial for this charge she has taken on life, on her work, which as she has put it, center around the question of power. One example is a conversation we had at the 2019 “Vision & Justice” convening, hosted by the Harvard Radcliffe Institute.

The second reason is that Carrie’s voice is not only an oracular instrument, but the elliptical pattern of scholarship I just described turned her into one of the best analysts of her own craft. She has learned about the history of aesthetics and racial formation. She visits archives. She has become, in effect, a researcher. These pursuits launched many of her projects, perhaps one for which she is best known, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, which was inspired by seeing the Zealy daguerreotypes in the Peabody Museum Collection at Harvard.

Carrie’s voice — her interviews — punctuate the volume, from the work of Fusco and hooks to that of scholars and curators including Huey Copeland, Deborah Willis, Robin Kelsey, Salamishah Tillet, Jennifer Blessing, Thomas Lax, Erina Duganne, Yxta Maya Murray, Kimberly Juanita Brown, and Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw. These works cover many of the projects in her oeuvre and disclose the remaining work that scholars can do to examine the innovations of her aesthetic enterprise.

“Untitled (Woman and Daughter with Makeup),” from the Kitchen Table Series, 1990.

Courtesy of the artist, Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, and the Mattress Factory Museum, Pittsburgh

“A Distant View (Malus-Beauregard House),” from The Louisiana Project, 2003. “Matera,” from the Roaming series, 2006.

© Carrie Mae Weems. Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York, New York

Gazette: Have you come to see aspects of Weems’ work in new ways after reading the contributions?

Lewis: What the dearth of scholarship on one of our most important artists who happens to be Black confirmed is that the fundamental, foundational changes happening in our fields are necessary, and that Carrie has been talking about the need for them for decades. After reading the volume, I think Carrie says it best: She’s eager for more. What the contributions show is that it is impossible to grasp the developments of intertwined fields of modernism, contemporary, and African diasporic art without understanding the interventions of and scholarly patterns surrounding the work of Carrie Mae Weems.