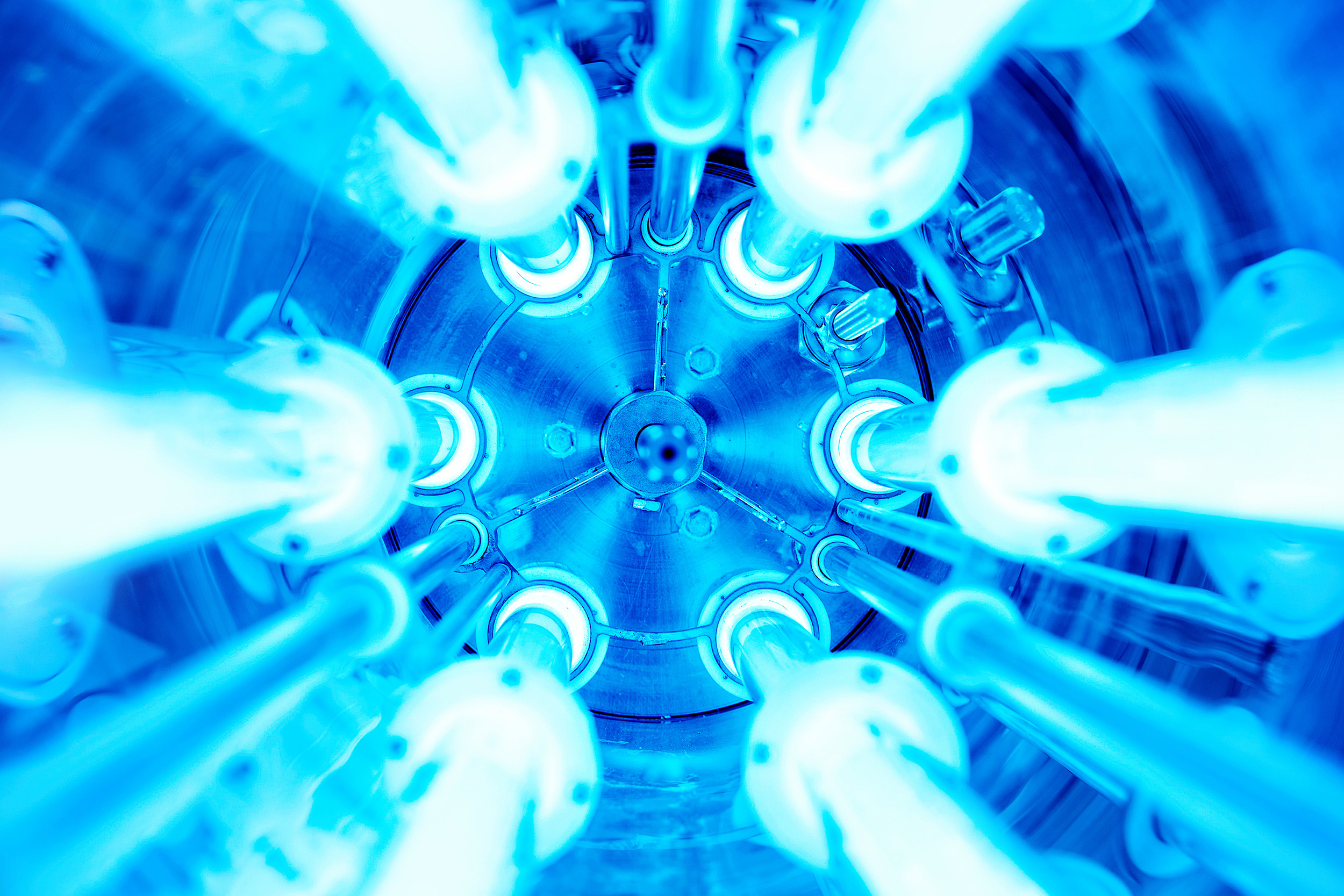

Ultraviolet lamps.

iStock

Preventing UV-associated cancers by altering skin pigmentation

Scientists are gaining a better understanding of the biochemical process behind pigment production.

A skin pigmentation mechanism that can darken the color of human skin as a natural defense against ultraviolet (UV)-associated cancers has been discovered by scientists at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Mediating the biological process is an enzyme called nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase (NNT), which plays a key role in the production of melanin (a pigment that protects the skin from harmful UV rays). Its inhibition through a topical drug or ointment could potentially reduce the risk of skin cancers, as presented in a study in Cell.

“Skin pigmentation and its regulation are critically important because pigments confer major protection against UV-related cancers of the skin, which are the most common malignancies found in humans,” says senior and co-corresponding author David Fisher, chief of the Department of Dermatology at MGH. “Darker-pigmented individuals are better protected from cancer-causing UV radiation by the light-scattering and antioxidant properties of melanin, while people with the fairest and lightest skin are at highest risk of developing skin cancers.”

Through their laboratory work with skin from humans and animal models, the MGH researchers mimicked the natural protection that exists in people with dark pigments. In the process, they gained a fuller understanding of the biochemical mechanism involved, along with their drivers and how they might be influenced by a topical agent independent of UV radiation, sun exposure, or genetics.

“We had assumed that the enzymes that make melanin by oxidizing the amino acid tyrosine in the melanosome (the synthesis and storage compartment of the cell) are largely regulated by gene expression,” explains Fisher. They were surprised to learn, however, that the amount of melanin being produced is in large part regulated by a much different chemical mechanism, one that can ultimately be traced to NNT in the mitochondria, the inner chamber of the cell, with the ability to alter skin pigmentation.

Researchers found that topical application of small molecule inhibitors of NNT resulted in skin darkening in human skin, and mice with decreased NNT function displayed increased fur pigmentation. To test their discovery, they challenged the skin with UV radiation and found that the skin with darker pigments was indeed protected from DNA damage inflicted by ultraviolet rays.

“We’re excited by the discovery of a distinct pigmentation mechanism because it could pave the way, after additional studies and safety assessments, for a new approach to skin darkening and protection by targeting NNT,” says Elisabeth Roider, previously an investigator with MGH, and lead author and co-corresponding author of the study. “The overarching goal, of course, is to improve skin cancer prevention strategies and to offer effective new treatment options to the millions of people suffering from pigmentary disorders.”

Fisher is a professor of Dermatology and Pediatrics at the Harvard Medical School and director of both the Cutaneous Biology Research Center and Melanoma Center at MGH. Roider is an attending physician in the Department of Dermatology at the University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland, and a visiting scientist at the Cutaneous Biology Research Center at MGH.