Will Mackin on duty in Helmand, Afghanistan, in 2008.

Photo by Mike McCaffrey

Animal encounters on the battlefield

Former soldier Will Mackin describes his short story process, and the role of animals in his next collection

When Will Mackin was in sixth grade, his English teacher, Mrs. Miller, assigned her students “The Outsiders,” a coming-of-age tale about two rival gangs. To reinforce the book’s central theme, she blasted The Who’s “Baba O’Riley” on a boom box at the front of the class, the lyrics (featuring a chorus with the phrase “teenage wasteland”) underscoring the angst-ridden struggle of the characters in the famous young-adult novel by S.E. Hinton.

“Because that song was very much in play at the time, it was very much part of what I felt was the real world and my interaction in it … [the song and the book] struck a chord,” said Mackin, the Perrin Moorhead Grayson and Bruns Grayson Fellow at the Harvard Radcliffe Institute. Kurt Vonnegut was next on the curriculum, Mackin recalled during a virtual Radcliffe talk last year. And “That’s all she wrote,” he said. “I wanted to tell stories, and I wanted to tell them in a way that affected me the same way that these had.”

That early impulse has blossomed into a successful writing career. His first book, “Bring Out the Dog,” based on his 23 years in the U.S. Navy, won the 2019 PEN/Robert W. Bingham Prize for Debut Short Story Collection and critical praise for its clear-eyed portrayal of the brutal, frightening, and tedious aspects of deployment.

At Radcliffe Mackin is at work on his next series, “Animals,” featuring a selection of stories left out of his first collection, many inspired by the animals he came across while on duty with a SEAL team in Afghanistan and Iraq. Whether he was trekking through darkened fields or searching houses for possible suspects, animals were in the fabric of his Navy experience, he said, helping highlight the absurdity of war.

During a phone interview late last year, Mackin described the packs of wild dogs that would rush him as he patrolled in the “middle of nowhere,” their angry barking amplified in his military headset; the jumping goats in the countryside, providing welcome comic relief; and a giant sleeping bull that he tiptoed past while on an evening raid. The eyes of pigs or donkeys would shine in his night-vision goggles, he said. “You could tell that they were thinking ‘What are you doing here?’ and it made me wonder, ‘What am I doing here?’” The animals, Mackin added, “made me reflect on a lot of things,” including pack mentality and the idea of war as a “uniquely human exercise.”

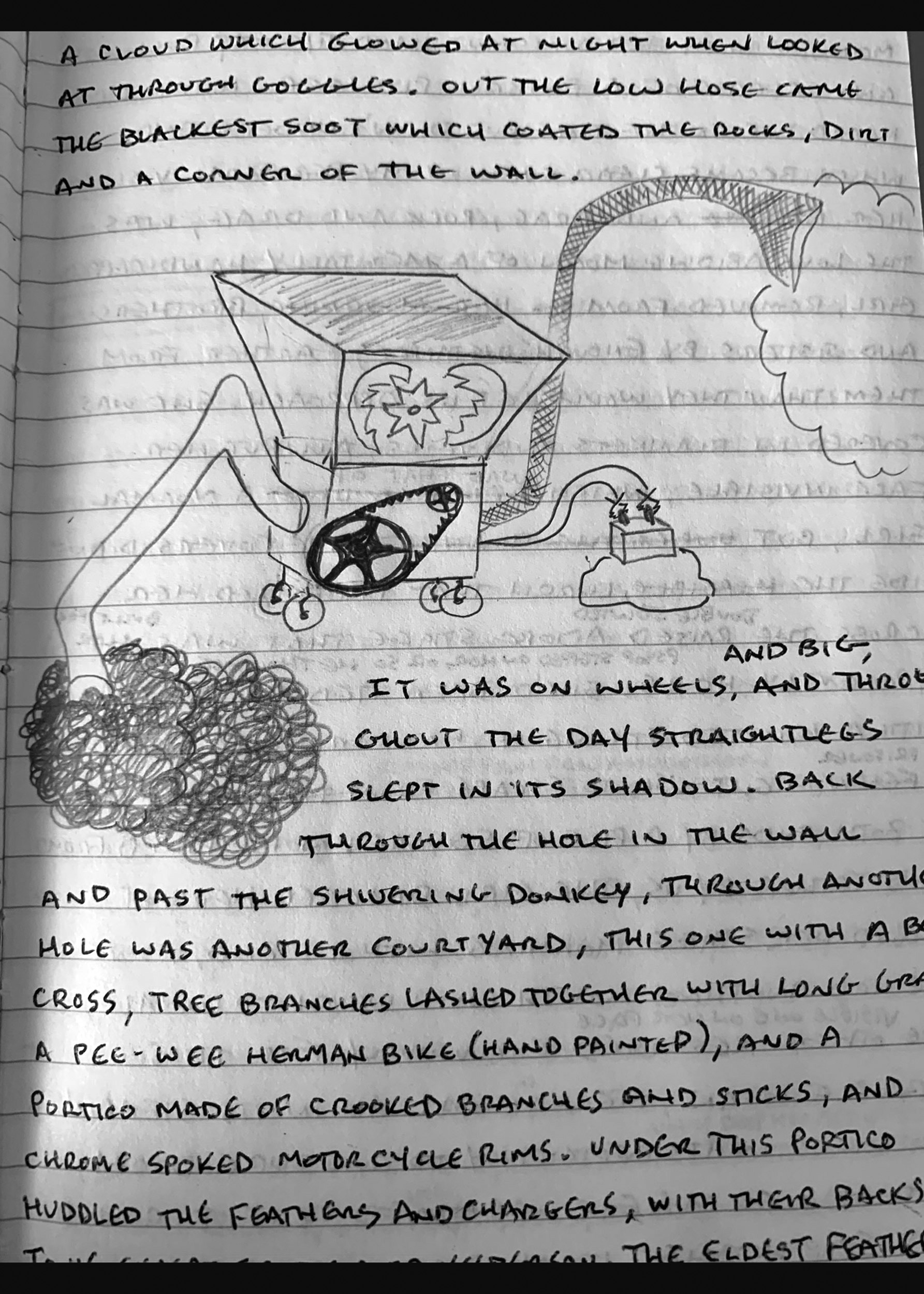

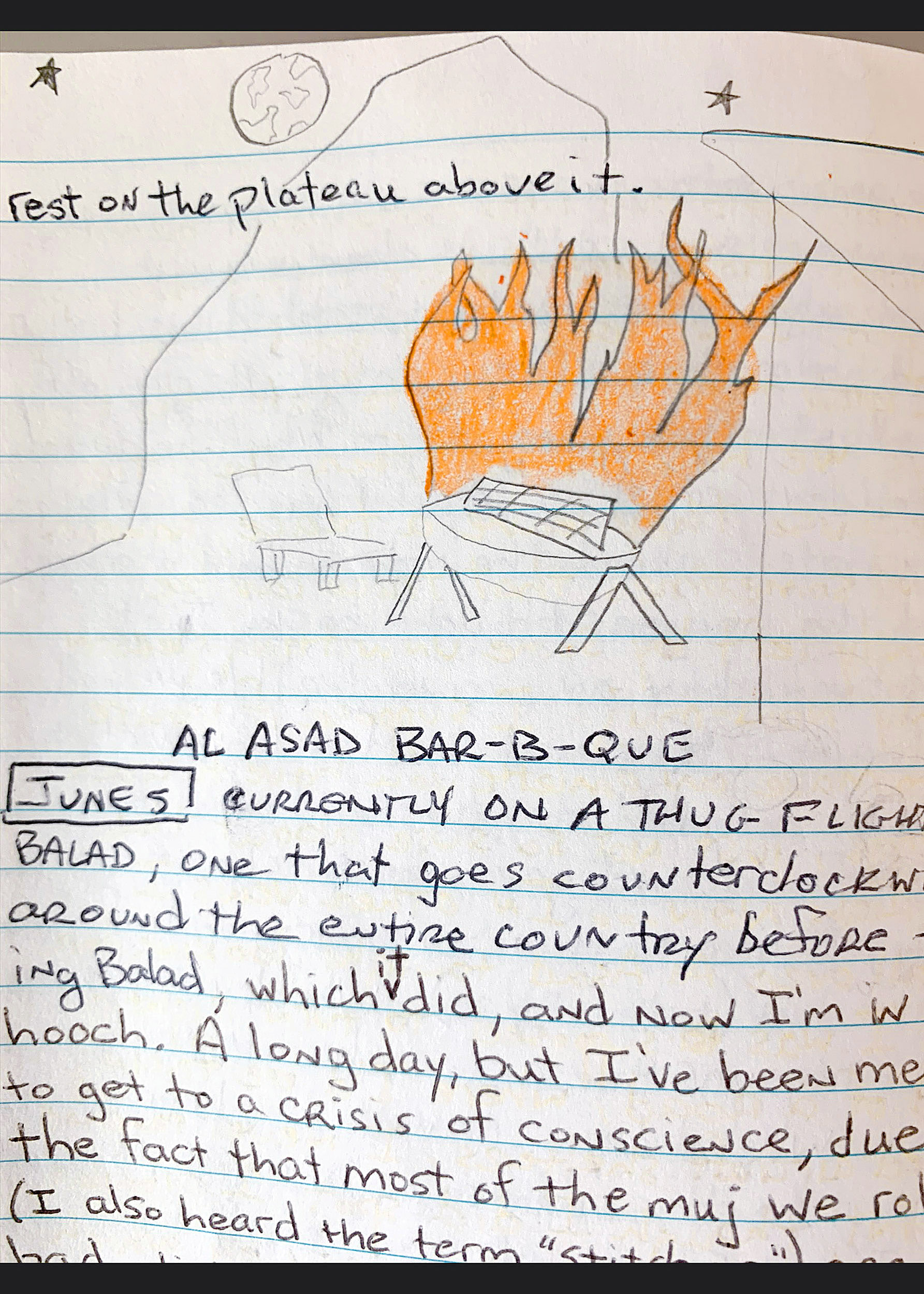

Outlining his process to the Radcliffe crowd, Mackin explained how an operational military template employed by soldiers heading into battle helped him organize his thoughts around character and storyline. In a military brief, Mackin said, the word “situation” refers to an enemy force’s position, numbers, and capabilities. “Artistically, though, situation, or forces, are more psychological in nature” he said, “and for that I am going back to the things that I put in my journal, or my memories, things that occurred to me that I can’t seem to forget.”

Pages from Mackin’s journal.

Courtesy of Will Mackin

Some of those journal entries center on the animals; others focus on the wails of a distraught infant. During training, his instructors would use the recording of a crying baby to simulate the kinds of interrogation tactics he and his fellow soldiers might endure as prisoners of war, Mackin explained. Then, one night overseas, they heard the panicked cries. “We had detainees that we had pulled off of various targets … their detention facilities were part of our camps, and we could hear interrogators playing the crying baby tape to them.”

Mackin, who called the tape “psychological warfare,” is hoping to explore “what became of the baby” in his new collection, weaving together tales about the life of the anguished child with his animal-themed stories. George Orwell’s allegorical novella “Animal Farm” and the Pink Floyd album “Animals” have been sources of inspiration, he said; so too has his Navy navigator experience. In his work relaying targets to incoming aircraft Mackin had to be brief, precise, and clear. The power of concision is central to his writing, he said, informed both by his military training and his love for poetry. Prior to joining the Navy Mackin studied with the poet Stephen Dunn, one of his literary idols, at a New Jersey community college. He later majored in English on a ROTC scholarship at the University of Colorado. (Poor eyesight ended his dream of flying jet fighters, but he flew as a navigator and later joined a special forces team in the Middle East for several tours of duty on the ground.)

With his poetry came “the beginning of what I tried to do with brevity and compression,” said Mackin. “I aspire to make every sentence as tight and as balanced as possible. And I think that comes from the rhythm of poetry, and the compression.”

Why not opt for nonfiction to capture real events? Mackin explained that while his work is grounded in fact, he turned to fiction ironically to make the material come alive. “The nonfiction I was writing was OK, but it didn’t capture what it felt like for me,” he said.

Ultimately with his work Mackin hopes to present war as “a more human endeavor,” he said, and to “describe an empathetic situation that hopefully the reader can relate to.”