Untangling a young patient’s autoimmune mystery

MGH’s Complex Care Service takes innovative, individualized approach to a case that resisted standard treatment

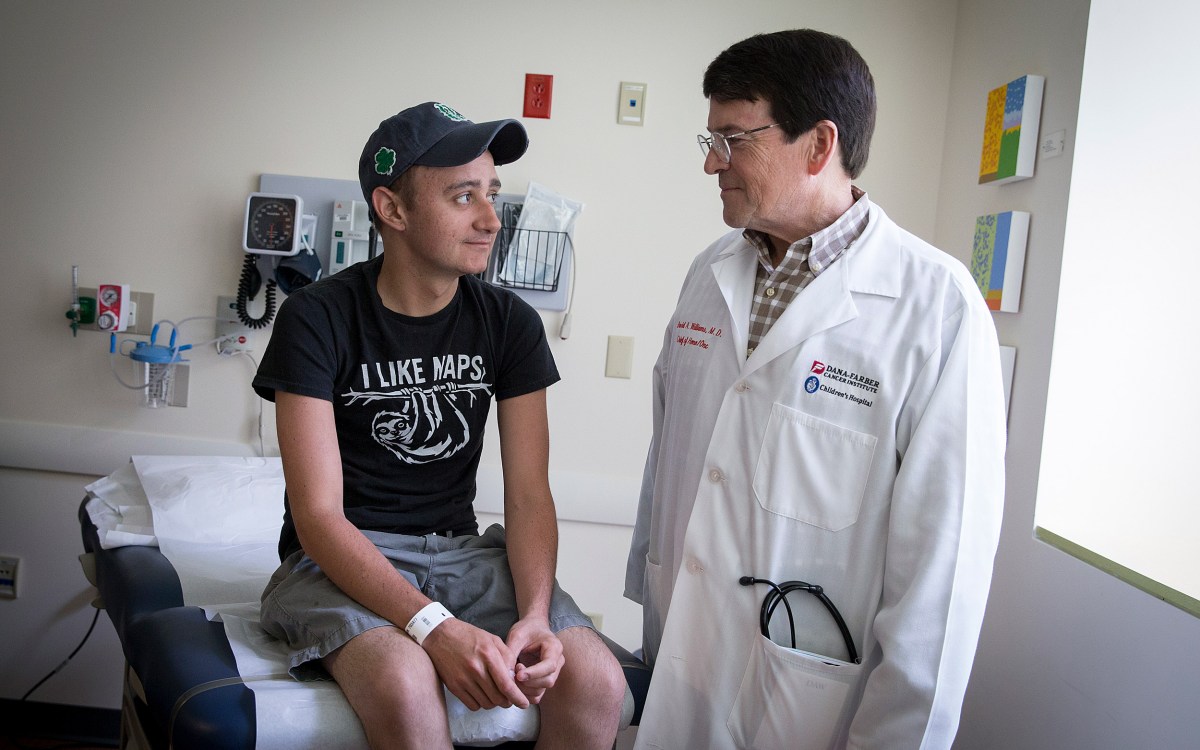

Members of the Complex Care Service team: Ryan Thompson (from left), Michael Mansour, Natalie Alexander, and Priscilla Parris.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The patient hadn’t eaten anything substantial for years due to nausea so constant that she couldn’t keep down solid food. Instead, she “ate” daily through an IV line. When asked what food she missed she said none: The very thought made her sick to her stomach.

Then there was the dizziness and the mysterious fevers — spiking to 106 degrees Fahrenheit at times — caused by bloodstream infections that struck without warning and that, when the doorbell rang, made her wonder whether she would make it through an otherwise routine visit with friends.

Now 23, she felt like it was an eternity ago when she was healthy and 15, playing soccer and running track. As her symptoms appeared and worsened, doctors near her home in Springfield were baffled. Her body seemed to be attacking itself, but tests for known autoimmune conditions came back negative. The standard options were quickly shrinking and solving the puzzle would ultimately require an innovative, highly individualized approach.

The Complex Care Service was created for patients who are, as the Medical School’s Ryan Thompson described, “the sickest 1 percent of the sickest 1 percent.”

In 2018, in desperation, the family agreed to an autologous blood stem cell transplant at a Chicago hospital. The transplant is a radical procedure that begins with the extraction of blood stem cells from bone marrow, presumably the abnormality’s roots, which is then treated with chemotherapy to get rid of the problem cells. Once completed, the collected stem cells were infused to repopulate her bone marrow, rejuvenate her blood and, hopefully, reboot her immune system. But her symptoms only got worse.

“The arc of her infections seemed to increase after the stem cell transplant,” said Ryan Thompson, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and a member of Massachusetts General Hospital’s inpatient Complex Care Service. “She has had a 180-degree change in her life since the initial onset of her illness.”

Thompson met the young woman, Emily Hedspeth, in August 2019, months before the coronavirus pandemic sent the world tumbling into chaos. She had come to MGH after her symptoms worsened following the stem cell transplant, and Thompson’s team was called in.

The Complex Care Service was created for patients like Hedspeth who are, as Thompson described, “the sickest 1 percent of the sickest 1 percent.” They are patients whose conditions ensure frequent hospitalizations and who otherwise might see different physicians and nurses on each visit. Instead, they are assigned a team that follows them over time, providing continuity in their care, allowing team members to gain experience with that patient’s particular case, and building trust with the patient and family.

After evaluating her in consultation with specialists, Thompson said, there seemed to be two issues at play in the young woman’s body. First, her gut lining was leaky, allowing bacteria and fungi into her bloodstream, where they caused infection. Second, her immune system seemed to be impaired and unable to fight off that infection. Even with a healthy gut, pathogens find their way into the bloodstream from time to time, Thompson said. Though that provided a starting point, they didn’t know the cause of each problem.

“There have been some times when she has been hopeless. We met her at the beginning of her steepest decline. There was a lot of anxiety at home not knowing when an infection would hit.”

Priscilla Parris, nurse practitioner for Complex Care Service

Hedspeth went home after being treated but, as feared, soon returned. Her second visit proved a marathon, stretching from days to weeks to months as physicians tried to tamp down the infections to the point where she could go home. After years of struggling with the condition, it was sometimes hard for Hedspeth to keep up her spirits.

“There have been some times when she has been hopeless,” said Priscilla Parris, a nurse practitioner on the Complex Care Service who works with Hedspeth. “We met her at the beginning of her steepest decline. There was a lot of anxiety at home not knowing when an infection would hit.”

Parris said Hedspeth is able to move around, but lives with a malaise, constantly fatigued and nauseous. A bright spot during that lengthy stay — it would stretch to three months — came compliments of something many young adults would rather skip: a test. Hedspeth had completed work toward her nursing certificate in May 2019, before entering MGH, but had missed the certification board exams. She worked with Parris to bone up, then took and passed the exam.

“I quizzed her a little,” Parris said. “We got her out to take the boards.”

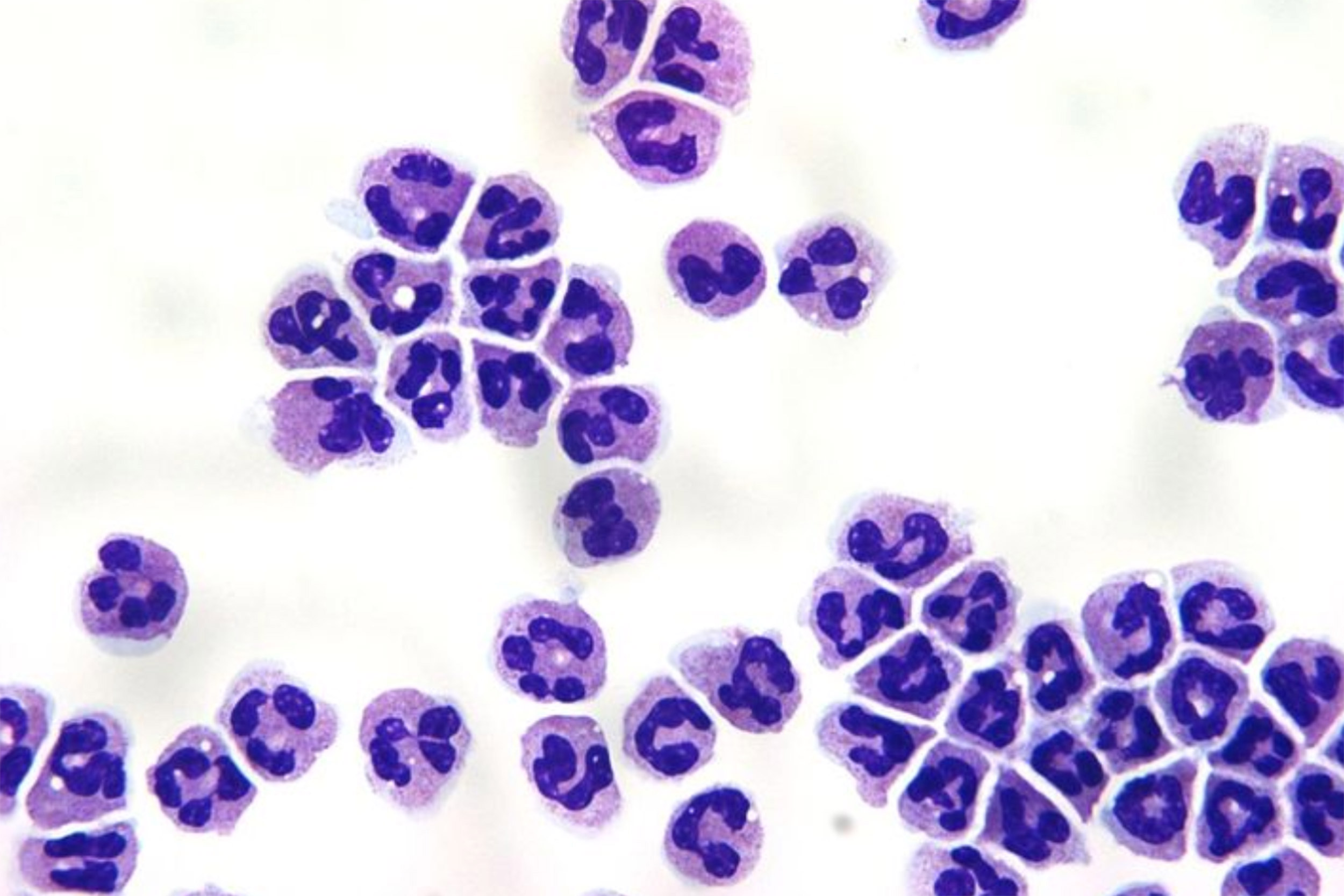

As it became clearer that an immune dysfunction was at work, Thompson called a friend from residency, Michael Mansour, who had an MGH lab focused on neutrophils, the most common immune cell in the bloodstream and a prime candidate for Hedspeth’s immune dysfunction.

Image demonstrates a Giemsa stain of normal human neutrophils.

Credit: Mansour Laboratory, MGH

Mansour’s lab was focused on research, not clinical care, so his involvement would lead to a unique, targeted clinical trial that enrolled just one participant — Hedspeth — and would narrow the sometimes insurmountable gap from lab bench to bedside to the length of the hallways between Mansour’s lab and Hedspeth’s hospital room.

The collaboration, detailed in a recent article in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, involved Hedspeth’s care team and members of Mansour’s lab, who, over the subsequent weeks, would gather in a conference room in MGH’s Immunology Department to brainstorm about the case. They’d project the latest lab results on a screen and review symptoms and progress in a search for new ideas and insights.

“We’d put arrows up on the boards, take notes, and think about potential problems that could fit Emily specifically,” said Mansour, an assistant professor of medicine. “There were many possibilities, but neutrophils were common to most of the problems she was having.”

The next step was to profile Hedspeth’s neutrophils. Mansour turned to research technician Natalie Alexander, a recent Boston College graduate, who had been working in the lab for three years. Alexander and Mansour met with Hedspeth to explain what the lab hoped to do with her blood samples and asked for her consent to proceed, a requirement since the work that would occur in Mansour’s lab, though presenting no direct risk to Hedspeth, would be experimental, not clinically validated. Hedspeth gave her permission. The plan then went to the hospital’s Institutional Review Board, which vets all experiments that involve human subjects to ensure that the research is conducted ethically and with informed consent.

With both permissions secured, Alexander set to work, running assays that tested the cells for how well they swarm toward potential pathogens and their ability to kill foreign invaders — specifically Candida albicans, a fungal pathogen in the gut microbiome with which Hedspeth had struggled, presumably due to its crossing into her bloodstream.

“She had a pretty clear neutrophil dysfunction against the pathogens I tested in the lab,” Alexander said.

Alexander visited the ward occasionally to gather additional samples and said Hedspeth was often in the room, sometimes with her mother. Interactions with patients are rare for those in research-focused labs, and it was the first time for Alexander. The two are about the same age and, as she talked with Hedspeth, Alexander realized that all that separated them was a twist of fate.

“She could easily be me. It was weird, this relationship I felt,” Alexander said. “I wanted to help. I was driven.”

Alexander threw herself into the project for the months of testing and analysis that followed.

“The assays took a lot of late nights, a lot of time,” Alexander said. “Science experiments don’t always work. I felt pressure to get answers and to get it right.”

Once the neutrophil dysfunction was detected, efforts shifted to restoring normal function. Alexander treated Hedspeth’s cells with four different cytokines — molecules important in cell signaling and in regulating the immune system. Two of the compounds, granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF) — both FDA approved for use in patients — improved Hedspeth’s neutrophil function significantly.

They selected G-CSF to administer to Hedspeth, in part because it had a better track record for safety. Afterward, they again drew blood and repeated the neutrophil analysis, finding that Hedspeth’s neutrophil function was similar to that in healthy controls.

The difference was clear in Hedspeth as well. Her immune system was able to tamp down the bloodstream infections that had led to dangerously high temperatures. Most importantly for her, she was able to go home for the first time in months to spend time with her family and see her two dogs.

Thompson acknowledged that the job is just halfway done. Hedspeth’s immune system is better able to fight off pathogens in her blood, but the gut dysfunction that allowed pathogens to cross into her bloodstream in the first place is still there. After treatment with G-CSF, her infections have decreased in frequency and severity, but they haven’t subsided. The arc of her infection, Thompson said, seems to be bending downward, particularly when measured by the number of days she is able to spend at home. Meanwhile, work has continued on the gut dysfunction, with two recent tacks seeking to optimize the microbes that live there and speeding the passage of food.

“We’re determined to see this through to an actual place of healing,” Thompson said. “Once she’s through this, she’s going to be one heck of a nurse.”