Houghton acquires 1st edition of 1st African American novel

A copy of the first edition, which was published in 1859.

Photos courtesy of Houghton Library

Henry Louis Gates Jr., who identified the book decades ago, works with N.H. dealer to add it to Harvard’s collections

Henry Louis Gates Jr. was wandering through a rare bookshop in New York City four decades ago when he spied an unusual-looking volume published in 1859. That discovery would change the history of African American literature.

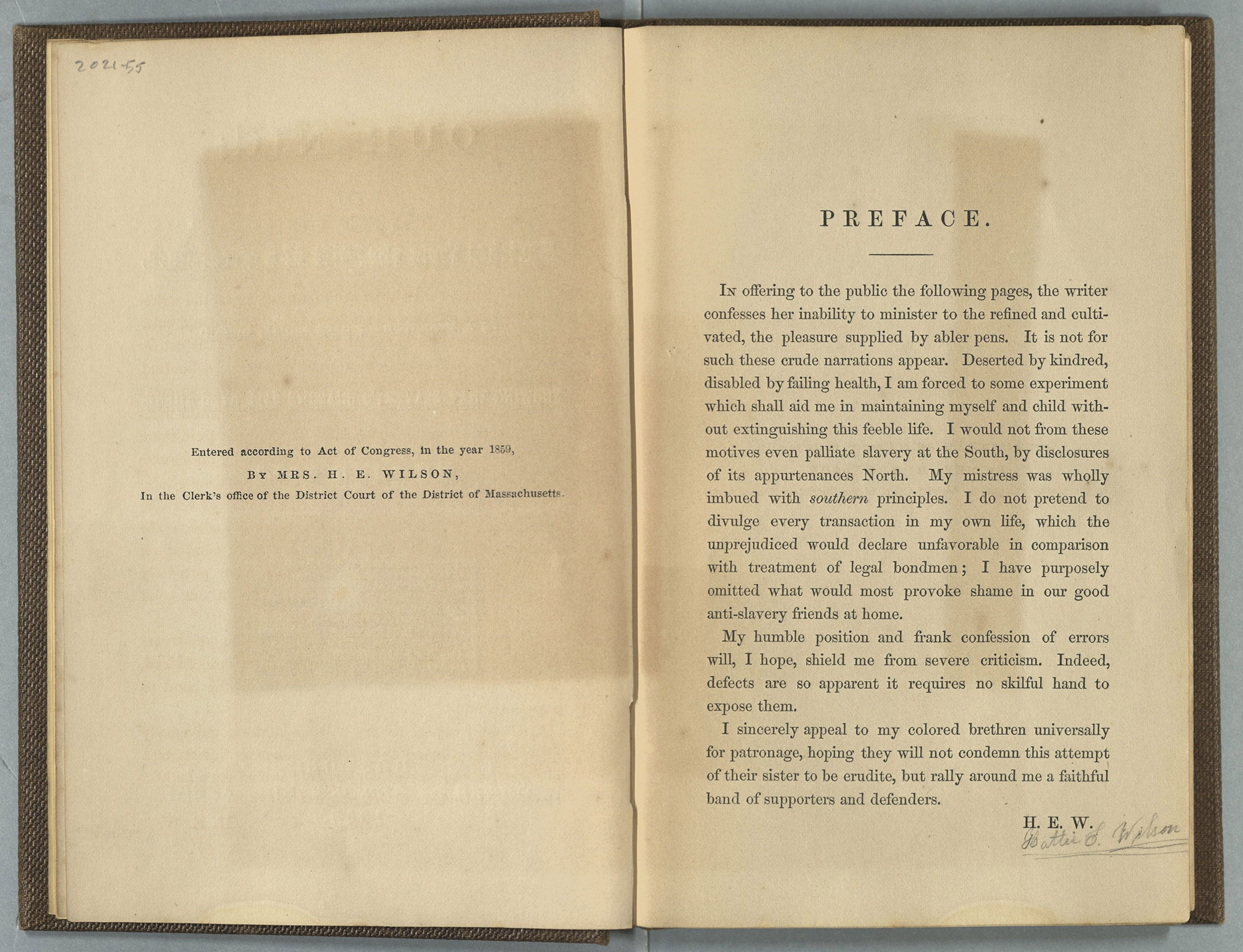

The book is subtitled “Sketches from the Life of a Free Black, in a two-story white house, North,” and its main title is a racial epithet. Eager to discover the identity of the author, who is not named in the book, Gates scoured archives and historical records. He determined the writer was Harriet E. Wilson, who was born a free Black woman in Milford, N.H., but spent most of her early life as an indentured servant. Gates republished the work with his findings in 1983 and established that Wilson’s book was the first novel published by an African American in the United States.

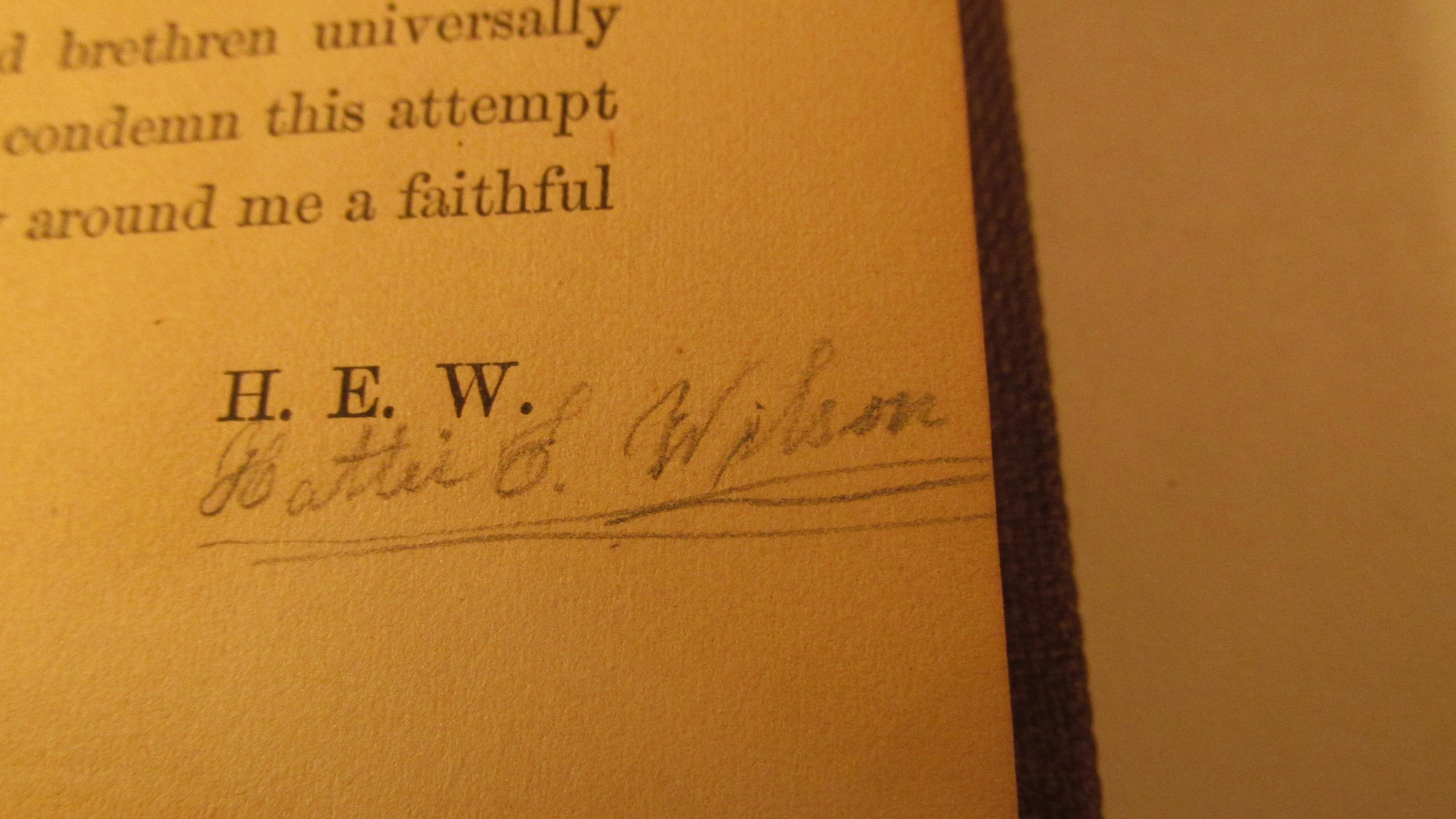

Now, with help from Gates, Harvard’s Houghton Library has acquired its own first edition of the work, containing what may be a signature of the author herself.

“As far as I’m concerned, any first edition” of the landmark novel “is very valuable,” said Gates, the Alphonse Fletcher University Professor and director of the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research. “And I want to acquire as many as I can. And this certainly is the most unusual one that I have ever seen because it has that name there.”

The saga began late last year when an antique dealer in New Hampshire found what appeared to be an early version of the novel deep in an old box of books. The dealer’s first email was to Gates. “I couldn’t believe it when he said he had a signed copy,” said Gates. “No one has found a signed copy before. And so I of course responded immediately and said I wanted to see it.” The dealer sent pictures of the book to Gates, who forwarded them to Leslie Morris, Gore Vidal Curator of Modern Books and Manuscripts at Houghton. Morris immediately got to sleuthing.

“To be honest, I’ve seen people write names in books a lot, and it could have been written by anyone,” said Morris. “I spent time trying to find documents with Harriet Wilson’s handwriting, and I couldn’t come up with anything. From the library’s point of view, we always like to know about provenance because when things turn up somewhat unexpectedly, you have to be skeptical until you feel pretty confident that they’re authentic.”

Instead, Morris turned her attention to the ownership stamp, a mark on the title page showing the book had once been owned by a jeweler in Gloucester, Mass., named Everett Lane. Earlier research on the ownership history of the novel has revealed that most copies, where early owners were known, had belonged to those who lived within a couple of counties of Wilson’s hometown in southern New Hampshire near Nashua, indicating the author may have been selling the work herself. “This copy fit the pattern. Gloucester is fairly close to Milford, so that seemed to put it more in Harriet Wilson’s circle of contacts,” said Morris.

Whether Wilson knew Lane seems unlikely, said Morris, since they’d have led “different lives.” There is also a note in the book, presumably by Lane, saying “Bought of H.P. May 1900,” just a month before Wilson’s death. Still, Morris acknowledges there is nothing that firmly “either proves or disproves” the signature, and that, regardless, having a first edition of such an important book in Houghton’s collection is paramount.

“We didn’t have a copy of it at Houghton, and it’s a book that we should have,” said Morris. “It’s a first in American literature, which is what we are known for, and it’s something that we’ve wanted to acquire for quite some time. We have several copies of Phillis Wheatley’s poems, for example, the first book of poetry published in North America, and the first book of poetry published by an African American. There are these monuments of Black literature that we are eager to collect.”

Professor Henry Louis Gates Jr. assisted Harvard in the acquisition of the book after determining it was the first novel published by an African American in the United States.

Kris Snibbe/Harvard file photo

The novel appears semiautobiographical, depicting the struggles of a protagonist, Frado, an African American girl indentured to an abusive white family, and offering up a searing account of racism in the North. The subject matter would have made the book stand out as there were many autobiographical Southern “slave narratives” published in the period, but this book takes racism in a region considered more enlightened, a fact that may have contributed to its obscurity given that it risked alienating its likeliest audience of abolitionists and sympathetic Northerners.

“My mistress was wholly imbued with southern principles,” writes Wilson in her preface. “I do not pretend to divulge every transaction in my own life, which the unprejudiced would declare unfavorable in comparison with treatment of legal bondmen; I have purposely omitted what would most provoke shame in our good anti-slavery friends.”

With financial support from Houghton and a donation from his personal funds, Gates made an offer to buy the book. Initially the dealer rejected it, opting instead to put it up for auction. But 24 hours later, Gates had another email in his inbox.

“The next day, he wrote to say he couldn’t sleep because he was so disturbed and that his wife felt that Harvard should really get it because of all the work that I’ve done to discover it, authenticate it,” Gates said. “And so he accepted our offer.”

During the 2020‒2021 academic year, Houghton Library has been highlighting its collection of Black historical materials in a digital campaign called “Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom: Primary Sources from Houghton Library.” As part of that effort, Houghton librarians will digitize the recently purchased novel in the near future, said Morris, to ensure that it’s “easily available to everyone.”

It’s an important acquisition for the library, but it’s also personally important to Gates, who reintroduced Wilson to the American public so many years ago and has faithfully kept up with the project — he teamed up with fellow historian Richard J. Ellis to write a new introduction and notes that included an updated account of Wilson’s life for a 2011 edition of the novel.

When the N.H. dealer and his son drove to Cambridge, the two posed for photos with Gates as they handed over the precious copy.

“It felt good,” said Gates. “I just felt like Harriet’s alive. It brought her back to life again for me.”