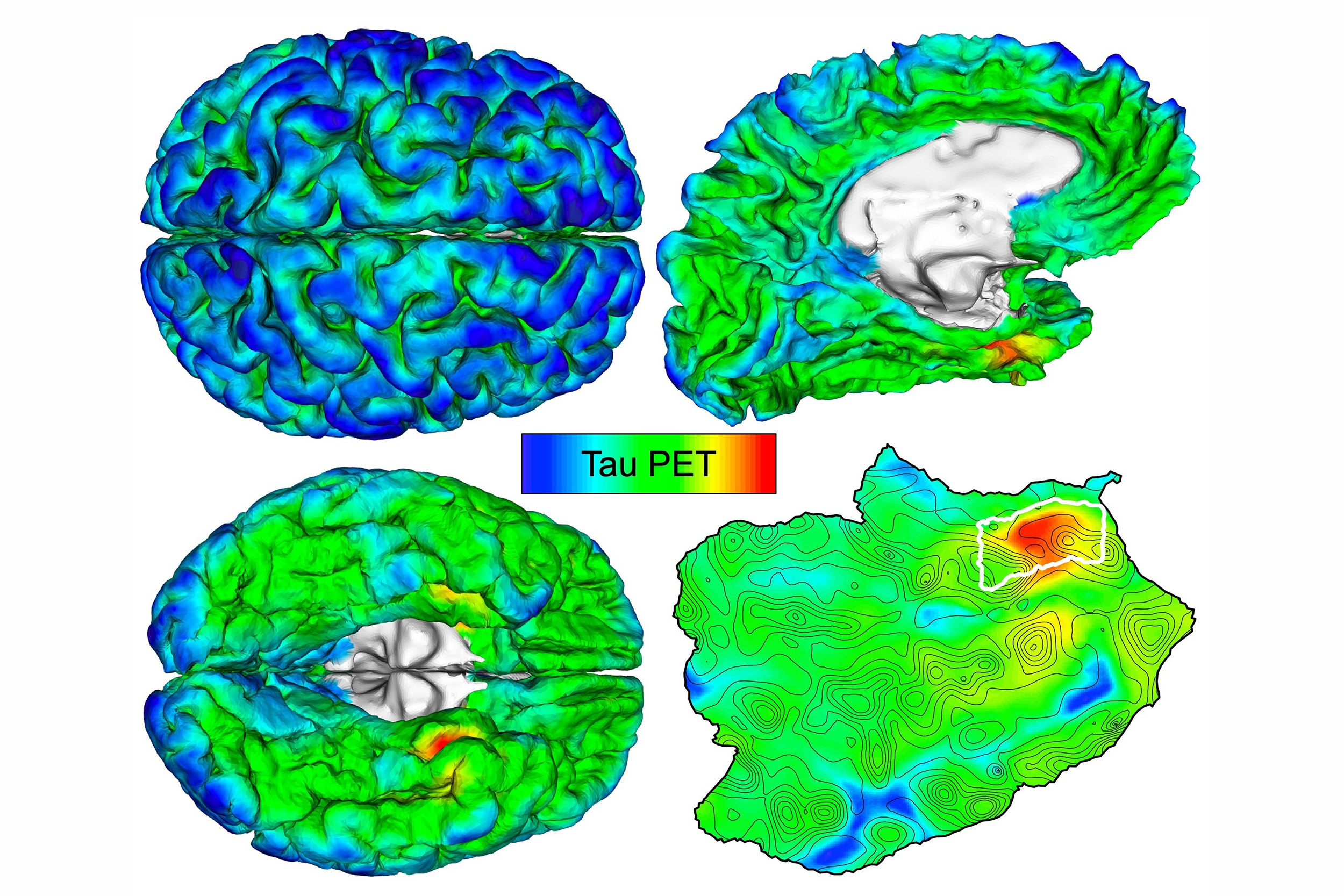

By mapping individuals’ unique brain anatomy, researchers have identified early tau PET imaging signals to track Alzheimer’s pathology. Left: Tau PET images for a person with normal cognition. Right: top, 3D brain surface rendering with tau PET overlay; bottom, flat map showing brain surface details, with cortical tau origin (rhinal cortex) outlined in white.

Courtesy of Justin Sanchez/MGH

Tracking the proteins before Alzheimer’s takes hold

Automated imaging may lead to earlier diagnoses, when treatments are most effective

Amyloid-beta and tau are the two key abnormal protein deposits that accumulate in the brain during the development of Alzheimer’s disease, and detecting their buildup at an early stage may allow clinicians to intervene before the condition has a chance to take hold.

A team led by investigators at Harvard-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) has now developed an automated method that can identify and track the development of harmful tau deposits in a patient’s brain. The research, which is published in Science Translational Medicine, could lead to earlier diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease.

“While our understanding of Alzheimer’s disease has increased greatly in recent years, many attempts to treat the condition so far have failed, possibly because medical interventions have taken place after the stage at which the brain injury becomes irreversible,” says lead author Justin Sanchez, a data analyst at MGH’s Gordon Center for Medical Imaging.

In an attempt to develop a method for earlier diagnosis, Sanchez and his colleagues, under the leadership of Keith A. Johnson of the departments of radiology and neurology at MGH, evaluated brain images of amyloid-beta and tau obtained by positron emission tomography, or PET, in 443 adults participating in several observational studies of aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Participants spanned a wide range of ages, with varying degrees of amyloid-beta and cognitive impairment — from healthy 20-year-olds to older patients with a clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia. The researchers used an automated method to identify the brain region most vulnerable to initial cortical tau buildup in each individual PET scan.

”…many attempts to treat [Alzheimer’s] so far have failed, possibly because medical interventions have taken place after the stage at which the brain injury becomes irreversible.”

Justin Sanchez, lead author

“We hypothesized that applying our method to PET images would enable us to detect the initial accumulation of cortical tau in cognitively normal people, and to track the spread of tau from this original location to other brain regions in association with amyloid-beta deposition and the cognitive impairment of Alzheimer’s disease,” explains Sanchez. He notes that cortical tau, when it spreads from its site of origin to neocortical brain regions under the influence of amyloid-beta, appears to be the “bullet” that injures brains in Alzheimer’s disease.

The technique revealed that tau deposits first emerge in the rhinal cortex region of the brain, independently from amyloid-beta deposits, before spreading to the nearby temporal neocortex. “We observed initial cortical tau accumulation at this site of origin in cognitively normal individuals without evidence of elevated amyloid-beta, as early as 58 years old,” says Sanchez.

Importantly, when the scientists followed 104 participants for two years, they found that people with the highest initial levels of tau at the point of origin exhibited the most spread of tau throughout the brain over time.

The findings suggest that PET measurements of tau focused on precisely individualized specific brain regions may predict an individual’s risk of future tau accumulation and consequent Alzheimer’s disease. Targeting tau when detected at an early stage might prevent the condition or slow its progression.

“Clinical trials evaluating the efficacy of anti-tau therapeutics would benefit from an automated, individualized imaging method to select cognitively normal individuals vulnerable to impending tau spread, thus advancing our efforts to provide effective interventions for patients at risk for Alzheimer’s disease,” says Sanchez.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health.