“My family’s from Louisiana, in the deep country; one side were preachers and one side were musicians, and somewhere in between comes poetry,” says Kevin Young ’92, who will begin his role as director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in January.

Emory University Photo

Kevin Young and a unified theory of Black culture — and himself

How it pieces together: Poet, editor, writer, curator, and soon-to-be museum head

An endless curiosity and love of words are central to the life and work of Kevin Young ’92, poet, author, poetry editor at The New Yorker, and newly named director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture. Young, who takes up his museum role in January, spoke with the Gazette about his passion for language, his Harvard time, and his goal of telling more “stories of Black lives and history.”

Q&A

Kevin Young

GAZETTE: You are something of a polymath. You are interested in art, history, music, language, among other things. You have written over a dozen books of poems and two nonfiction works, with the latest on the history of the hoax. You were a curator of a poetry library, a professor of English and creative writing, a library director, and soon-to-be head of a museum. How do you see that all fitting together?

YOUNG: For me, it’s just part of following the path. And especially, I think, African American studies, or culture, or poetry has this quality that, if not polymath, then means exploring lots of sides of writing. Many of the great poets from Langston Hughes to Gwendolyn Brooks also wrote fiction and great nonfiction. I think it all stems from being a poet and that [wide-ranging] curiosity. To me, poets draw connections between things that might not seem like they’re like each other, but are, and those kind of metaphors that you make in your poetry I try to make between art forms. Rather than weaving them together or connecting them, you’re kind of “uncovering the weave” as someone said. You’re showing what is already there. Sometimes that involves leaps of imagination.

For me, writing my first nonfiction book like “The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness” was really important because in it, I was trying to create almost a unified theory of Black culture. In it I talked a lot about storying and improvisation, and these kinds of ways that Black creators encode meaning — whether they’re enslaved or whether they’re making hip-hop in a basement somewhere. I really wanted to draw that connection. I realized that in some ways I was trying to write about what was Black about American culture — which turned out to be a lot, if not everything. And then at the same time, as I kept writing the book, I realized I was also trying to write about what was Black about Black culture, what was unique about it. And that quality, I think, is what makes it so special. And it’s something that it just so happens is explored in depth at the Schomburg Center and also now at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, which I’m really excited to helm starting in January.

GAZETTE: You mentioned the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. How did you make that transition from author, poet, teacher, and poetry curator to director of the center, a research library of the New York Public Library, and now to the head of the museum?

YOUNG: I was teaching at Emory University, and I was also a curator in the archives there in its Rose Library. I was getting collections and papers, among them, Irish collections. (It was sort of amazing to come full circle with my former Harvard Professor Seamus Heaney, whose letters are there, for instance.) And then, I was realizing that there was something to be done at a place like the Schomburg Center, which for almost a century, has been gathering Black material, keeping it safe, and providing access to it. And that’s what really drew me there. During my time, we were able to really get a lot of collections — from James Baldwin to Sonny Rollins, from Harry Belafonte to Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee. Those kinds of archives were really important because one of the things we were doing was celebrating Harlem as this rich cultural capital, and all those people had a relationship to Harlem, either by birth or by longstanding connection. And so that was really important. And the National Museum to me is a chance to do that even more, telling that story through objects, exhibitions, and events to a broad audience.

GAZETTE: What ways will you try to expand the story of the Black experience in your new role?

YOUNG: The museum has done such a good job already of telling that story. While it’s been open only four years, it has had a huge impact. My goal is to really continue with that, to see how we can tell more stories of Black lives and history. I’m sure that art and perhaps poetry will play a big part in it. It already does there, but I will look to expand that. I’m thinking too about some of the digital conversations and innovations that are necessary in this moment — a moment that is both unprecedented, and sadly, quite precedented. And so trying to capture that in a museum setting, through collecting and curating, I think is really important.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture opened its permanent home in September 2016.

Photo by Alan Karchmer

GAZETTE: How do you think about approaching the work when so many stories of the Black experience are missing or have been intentionally deleted from the historic record?

YOUNG: I think there is an element of recovery. And I think something like the anthology I’ve just released, highlighting Black poets from the colonial period to the present, shows that. But there are also lots of individual people and places that have preserved this material. And I think that’s one of the things that’s really powerful about the museum, for instance, as you see people coming out of the woodwork to donate things they’ve kept in their families, whether that’s family Bibles, or memorabilia, or things from fraternal organizations, or people’s personal activism and accounts. I think all of that is part of our archive that often lives in people’s houses, and in people’s memories. Black folks, I find, have been telling their stories for generations, and one of the things the museum has done is bring those things to light and bring them under one roof, and of course, provide them digitally, and that is why it’s a national treasure.

GAZETTE: Have your goals or your approach to the museum’s mission changed given what many are calling a national reckoning on race?

YOUNG: I think it’s only deepened and made it more urgent. Over the summer, at the Schomburg Center, we issued a Black Liberation Reading List that was incredibly popular. We had something like 30,000 electronic checkouts in a month via the New York Public Library’s e-reader app, SimplyE. So continuing that kind of digital work is critical at the museum. And I think people, especially right now, are looking for curated experiences for themselves and their kids — ways to explore this moment and talk about it with their youngsters. What the National Museum does with exhibitions that tell the whole story of African American history is so important, as well as how they can focus on one aspect of that history, from music to sports to World War I. I am eager to help tell those stories there, to audiences in person and online.

“That was really important to me, to be able to try to write in a contemporary vein of driving the landscape or experiencing America from that inherent but often unspoken Black point of view.”

GAZETTE: Do you think poetry as a form is uniquely suited to respond to this moment?

YOUNG: Just since the quarantine, I’ve seen so many poems wrestling with this moment of the pandemic, and its terrors, its boredoms, its effect on love and light. But then also the other pandemic of racism — you see poets really wrestling with an injustice. And so I think poetry is in a different state and calls in many ways for a different poetry. What’s fascinating to me is more than other art forms, poetry can respond in the moment. Poetry is often about moments, these flashes of lyrical beauty, but also pain. I think American poetry has a particular fluidity, or ability with that right now. And so I’ve been really impressed and blown away by poems that I accepted at The New Yorker a while ago that suddenly seem really relevant for the moment, and poems that are new and fresh and about the moment that I think will last the test of time.

That’s another test of a poem, that it speaks in different ways at different times. A case in point: Marilyn Nelson’s poem “Pigeon and Hawk.” It’s a tense narrative of recollection, filled with questions about a younger self trusting someone years ago, getting a ride home with them, and then realizing only later this might have been very dangerous. At the end she writes, “a cop might take his knee off a black man’s throat.” I took that poem a year ago, and the sad truth was it was incredibly relevant over the summer, right now, and I fear into the future. And so I think some of those things are important to have said. Her poem’s acknowledgement of the realities of racist violence — which some might have said in the abstract, that would make it dated — is sadly evergreen. So, it’s really important for poems to testify.

GAZETTE: Where do you think your own love of words came from?

YOUNG: I liked all the subjects, math and science too! My parents were science people and believed strongly in education and being well-rounded. But I definitely loved writing. I used to write little stories when I was a kid, and I think it was a bit of a surprise to my parents, but they were also encouraging. My family’s from Louisiana, in the deep country; one side were preachers and one side were musicians, and somewhere in between comes poetry.

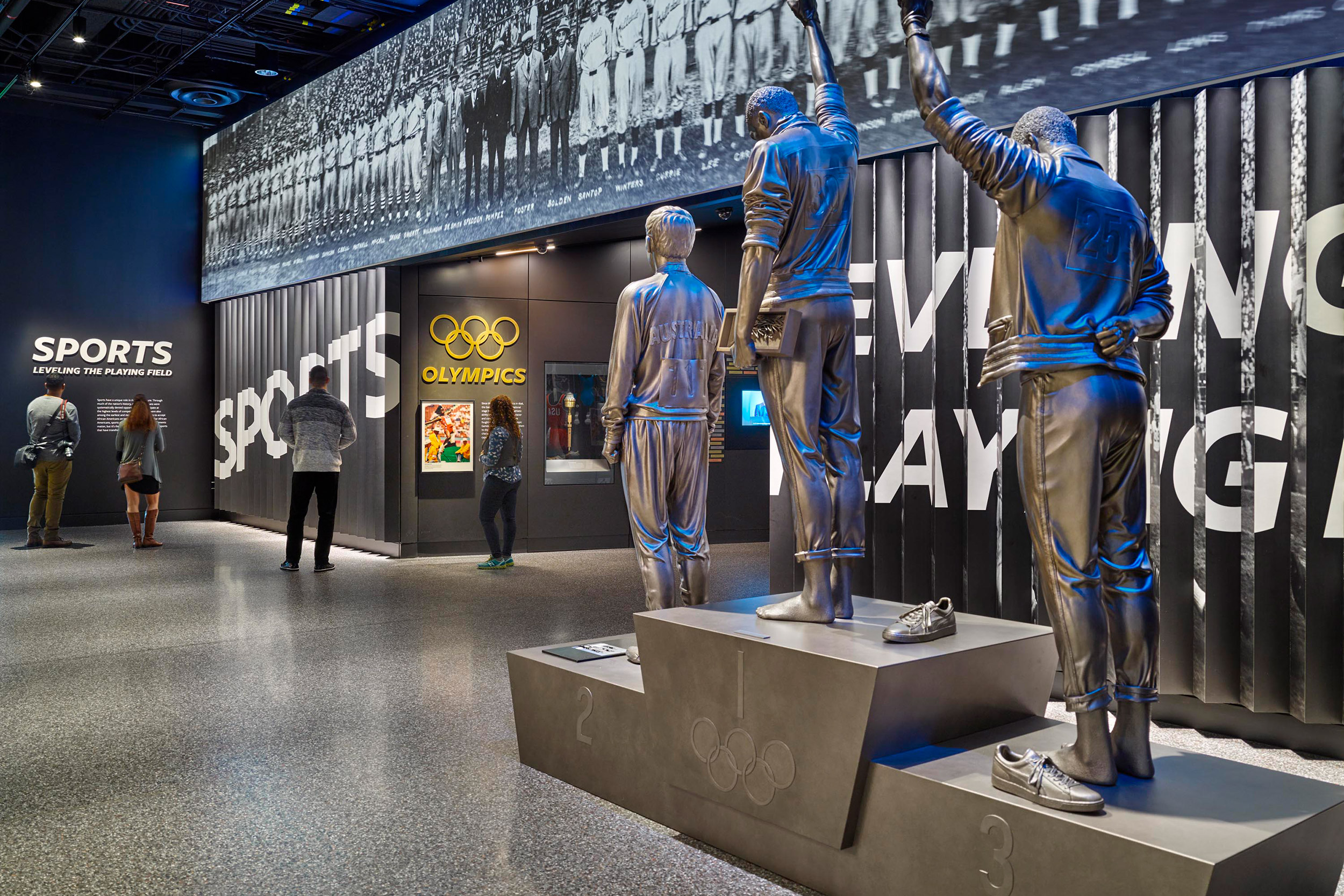

Exhibits at the National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington, D.C.

Photos by Alan Karchmer

GAZETTE: Do you remember what those early stories were or whether there was an early book that made you want to write?

YOUNG: I grew up in part in Kansas, and that’s when I started really writing in earnest. I was fairly young, 12 or 13. Soon I would just get whatever was in the local chain bookstores, which weren’t the best (and don’t even exist anymore), but it made me read really eclectically. The book I first fell in love with right when I was going to College was Rita Dove’s “Thomas and Beulah.” She won a Pulitzer for it, and I remember reading about that in Essence magazine, which my mom got, and saying to myself, “What? This Black woman was the second Black person to win a Pulitzer in poetry?” It had been four decades since Gwendolyn Brooks had won. I ordered the book, and I remember reading it. Around the same time I went down to Louisiana right before I started freshman year. It was there I realized that poetry wasn’t like some abstract thing but that it could be about my grandparents; it could be about the dirt, and the mud, and the car that sat in the yard that we used to play on till we learned it was full of snakes, and that there was a kind of poetry all around me. And so the way that my family told stories and talked and laughed and loved music and dance, all that was part of the poetry I started writing when I got to school.

GAZETTE: Had you written any poetry before coming to Harvard?

YOUNG: I wrote a lot a lot of bad poetry before coming to Harvard.

GAZETTE: What made it bad?

YOUNG: The things that were interesting in it, I suppose, were things that I later became better at. I was trying to talk about loss and love, but it was sort of abstract or mythic in a broad way. And I hadn’t realized yet the mythic that lived in the everyday, which is what I really learned in writing about Louisiana. Those poems made up my creative thesis at Harvard, which a year or two later became my first book, “Most Way Home.”

My other poetic realization that I came to at Harvard became the last section of my first book: writing poems with a protagonist who was just assumed to be Black. It wasn’t like the speaker spoke about being Black necessarily; it was more like that was part of their fiber. That was important for me, because I hadn’t yet seen either sets of my grandparents in poems, so it made me want to make myth of family and red mud. While I certainly had seen Black speakers, it took me a while to learn the ways that Langston Hughes — who had lived in Kansas like I had — had these great speakers who were bellboys, or cooks, or washerwomen, and they were singing or speaking of their own experience and lives, and that was just assumed. That was really important to me, to be able to try to write in a contemporary vein of driving the landscape or experiencing America from that inherent but often unspoken Black point of view.

Now I look back on some of those poems, and I appreciate what I was trying to do: to write untranslated poetry. I would just refer to “the kitchen,” which if you’re Black you know means the back of your head. And so there were things like that, that I really didn’t want to decode. I wanted it to be part of the pleasure of the poem. And I think people like Seamus Heaney, who was my teacher at Harvard and who was writing of his home in Ireland and “the weather of words,” and the poetry I was reading by Lucille Clifton, whom I later got to know, both did that, assuming that their speakers and readers needn’t necessarily explain their origins. And that was a great, liberating thing for me.

GAZETTE: What initially drew you to Harvard?

YOUNG: I was in Kansas, and I really wanted to be in a place where I could study whatever I chose to study and where I would be pretty much guaranteed that there would be excellent professors and excellent resources. I didn’t fully know how great the resources were, I think, until I got there. But I also knew that I was hungry for the kind of shared experience that Harvard ended up offering me. I got there and founded literary magazines and met my friends, who became writers and filmmakers — people like Colson Whitehead, my good friend from College, who was a year ahead of me. We worked together reviving Diaspora, the Black cultural student magazine. Things like that were really important to me before I sort of made my way in the poetry world. It was a good fit — I liked that Harvard had opportunities, but they didn’t always present themselves. You had to kind of hunt them down. And that was good for me too.

“[Marilyn Nelson’s] poem’s acknowledgement of the realities of racist violence — which some might have said in the abstract, that would make it dated — is sadly evergreen. So, it’s really important for poems to testify.”

GAZETTE: Now, as the author of numerous books of poems, the editor of several others, and the poetry editor of The New Yorker, what do you consider good poetry?

YOUNG: Good poetry all has a similar quality, which is it moves us; it sings to us; it says something perhaps surprising, or unexpected. Or maybe it says something we hadn’t realized we thought or knew or felt. It gives voice. But it also seeks silence. Those kind of qualities are in all good poetry to different degrees. The best poetry, I think, is really layered. I happen to like a poetry that often sucks you in. Someone like Langston Hughes or Lucille Clifton can seem on the surface fairly simple. And then you start to look at it and you realize that layered effect. It’s almost like a painting that draws you in and the closer you get, the more you can see. That mix of surface and depth is really important. And readers respond to that. Sometimes they’re responding to the depth that peeks through and that reaches them even through what might seem kind of hard to parse at first.

One of the pleasures of poetry is it’s like a good song. You can sit and listen to it a lot of times and hear something different. The poetry I’m drawn to, or that I’ve taught, is like that. There’s a poem in my recent anthology, “African American Poetry: 250 Years of Struggle & Song,” by Yusef Komunyakaa that I was recently reading and talking about with a group of students, his “Ode to the Maggot.” And I was just blown away by how much more I saw in it, and I’ve read it 1,000 times. That is what the test of poetry is. I try to get readers to think about the ways that the poem deepens.

I also think you should meet a poem much like you should meet a person, a little bit open. Sometimes we forget that, and a poem is a good reminder — you have to meet it where it lives. But a poem also lives in lots of different places, and those poems we love, and memorize, and keep, they live on in the body. That kind of physical embodiment is really profound and unique among most art forms, and that’s one of the things I treasure about poetry.

GAZETTE: Given all the demands on your time, are you able to continue to write?

YOUNG: It’s often hard to find time always, but I’m obviously rejuvenated in some key way by this kind of very meaningful work in archives and libraries, museums and magazines. And it’s work that moves people. I’m always touched when people say something to me about a poem they read in The New Yorker that I picked, or something I published; or they saw and read the Schomburg Black Liberation Reading List and were moved and discovered this whole other side of themselves; or visited the NMAAHC and had a moment to think about their own creativity and their own place in history. I think that’s so moving to me, and also part of why I write, and will keep writing.

Interview was gently edited for clarity and length.