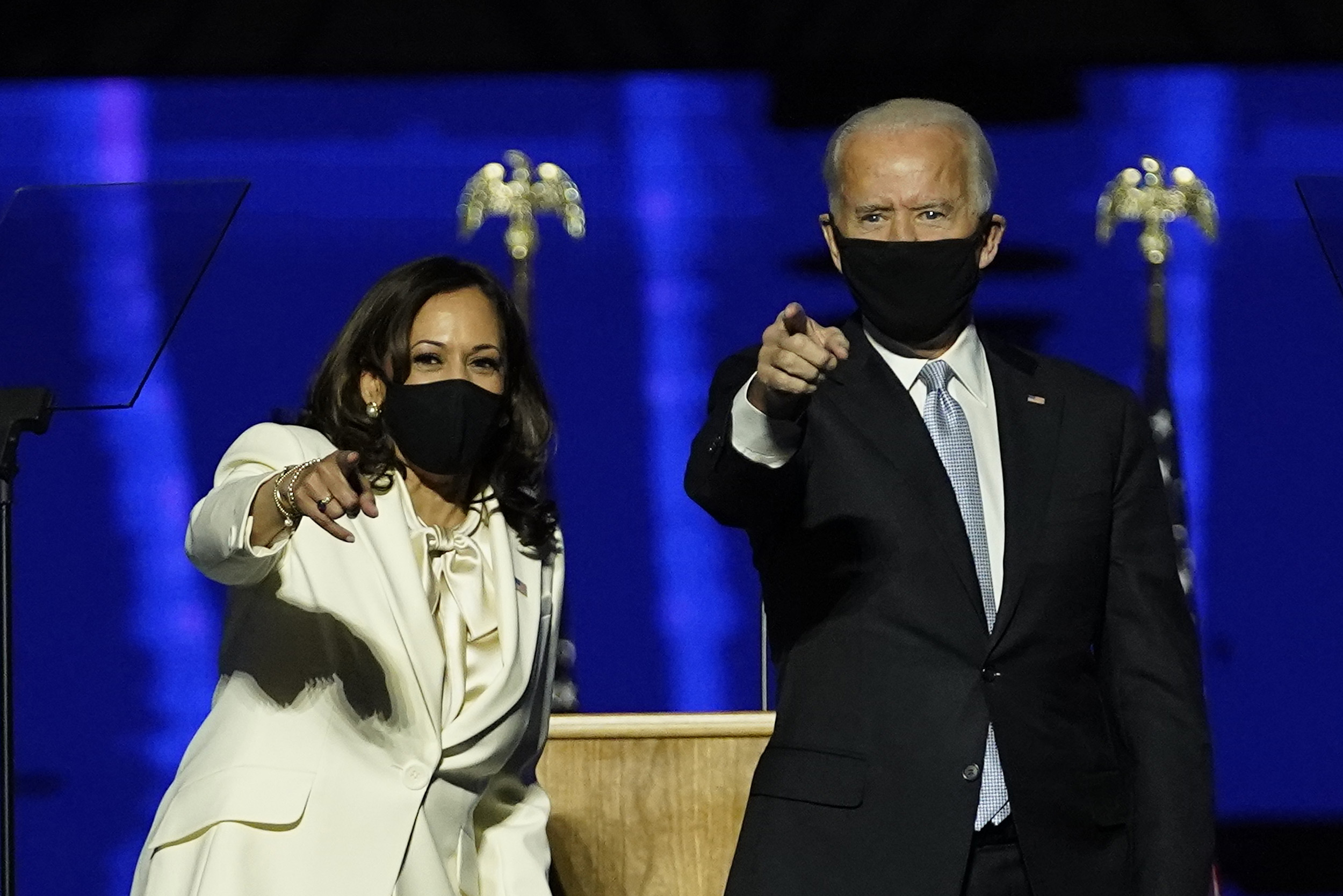

Vice President-elect Kamala Harris and President-elect Joe Biden at Saturday night’s event in Wilmington, Del.

AP Photo/Andrew Harnik, Pool

After a hard election, the real work begins

Looking for hints of future prospects in the past and predicting what lies ahead

The presidential election ended before lunch on Saturday in favor of former Vice President Joe Biden and his running mate Sen. Kamala Harris, the first woman and first woman of color to win the vice presidency. But in some senses the contest hasn’t ended but just entered a new phase.

Months of bitter Democratic primary campaigns had segued into an even harsher presidential election featuring two starkly different views of America, championed by Biden and Republican President Donald Trump. The national debate raged over the handling of a pandemic that has killed nearly 240,000 Americans and sickened about 10 million; racial justice; climate control; inequities in income, education, health care; judicial appointments; immigration reform. The nation has a new leader, a somewhat more evenly split Congress, and a Supreme Court that appears much more conservative than the population it serves. A house still divided against itself.

In a speech Saturday night, President-elect Biden laid out all the familiar challenges, suggested that his first order of business would be to rein in the COVID-19 outbreak, and declared an end to “this grim era of demonization in America.” University scholars, analysts, and affiliates take a look at what the election tells us about the prospects for greater unity and progress, and offer suggestions and predictions about where the new administration will, and should, go.

Celebration erupted in Harvard Square following Saturday’s announcement that former Vice President Joe Biden had won Pennsylvania, locking in the the U.S. presidential election.

Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

First takes

What is your initial response to the election results and do the results offer any insights into the future?

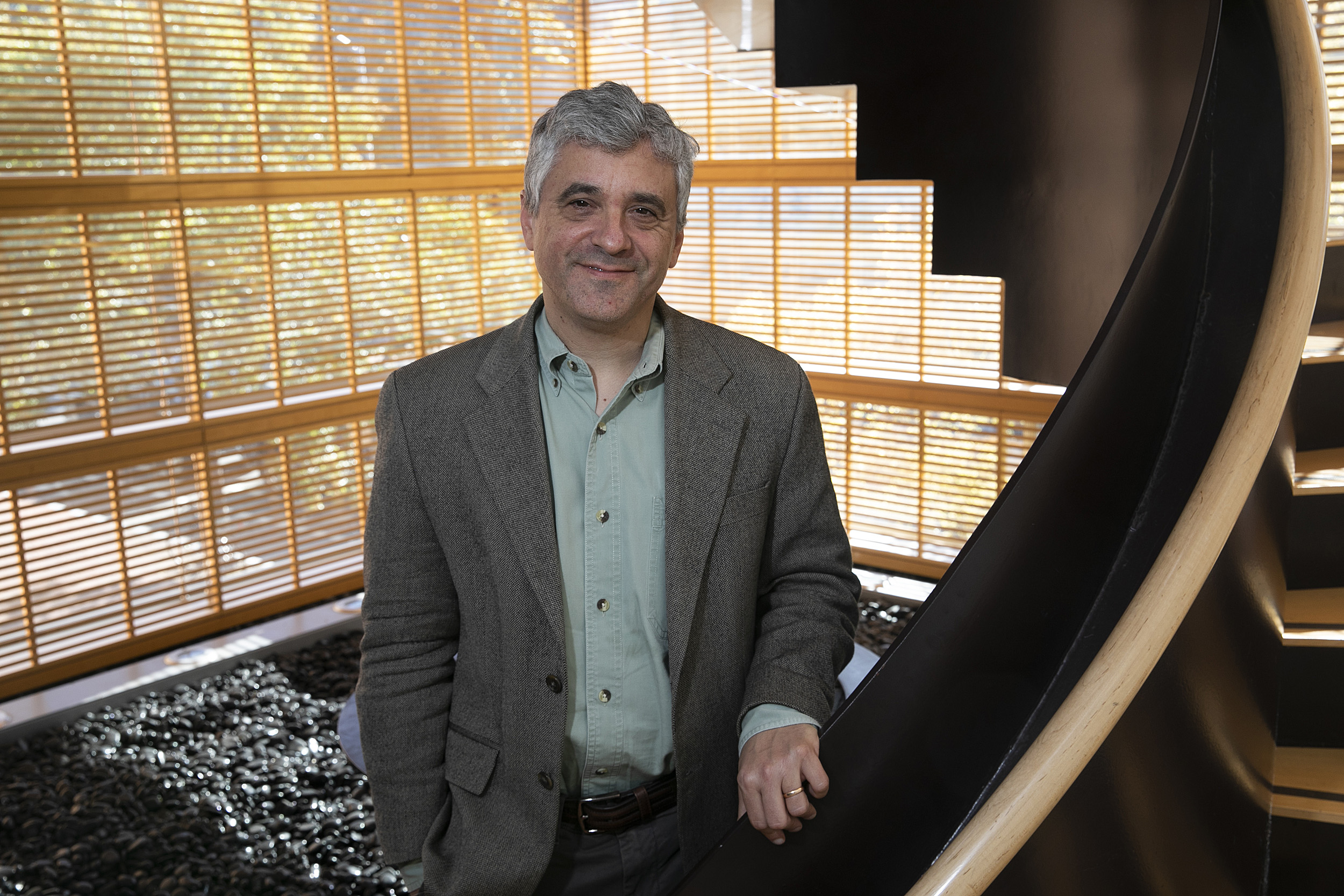

Steven Levitsky

Professor of Government, director of the David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies

How rickety and out-of-date our electoral administration is, though it was robust enough to withstand an extremely difficult election. The health crisis, the massive increase in mail-in voting, and extreme polarization — any number of things could have gone wrong. If there had been one militia attack or one case of fraud, this could have escalated into something quite serious. The election was extraordinarily smooth, and Trump’s efforts to overturn the results have been pathetic. He hasn’t been able to mobilize support.

Beyond that, it reinforced what we already knew. We have a deeply divided society. The opposition to Trump and Trumpism has always been a majority but it’s a pretty narrow majority, and that is going to continue to affect both policymaking and democracy for a number of years. This was a huge moment. Any time you remove someone who is not committed to democratic norms and practices, it’s a big day. But in spite of Biden’s nice words, polarization is not likely to stop.

None of this was terribly shocking from a political science standpoint. The U.S. system was not designed for two extremely polarized, highly disciplined parties. We are headed for extreme dysfunction. It wasn’t long ago that many scholars believed and taught that our system worked well. This has changed a lot in the last decade and certainly in the last four years. The question we are now asking is: What kind of institutional reforms are needed to fix it?

The nature of our polarized society is a terrible match for our institutions. Political scientists are taking the phenomenon of populism much more seriously than a decade ago. After such a disastrous response to COVID that has resulted in loss of 230,000 lives in less than a year, the fact that nearly half the country supported this incumbent president is a striking phenomenon that needs to be better understood, and still needs study.

This election reaffirmed that we are sliding into minority rule. The fact we were waiting around for days to find out if the guy who won by 4 million votes had enough electoral votes is a major disaster. We have a system that consistently rewards a party that consistently fails to win the majority of the popular vote. Democrats have won the last seven out of eight elections, but Republicans have governed us 12 out of the last 20 years.

Tomiko Brown-Nagin

Dean, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study; Daniel P.S. Paul Professor of Constitutional Law, Harvard Law School; and Professor of History

The United States has long been said to symbolize openness and opportunity. Breakthrough accomplishments in law and society make real these ideals. The ascent of Sen. Kamala Harris to vice president-elect constitutes such a defining moment, suggesting to Americans who value multiracial democracy and equal opportunity that both are genuinely possible in this country. As the first woman — and more particularly, the first African American and South Asian woman — to achieve this office, Harris sends a message to women and people of color that their talents can be recognized and rewarded in public life. Her rise signifies to Americans who see themselves in her that they are valued stakeholders in our democracy. This sense of belonging is fundamental to the legitimacy of U.S. institutions.

Those who danced in the streets Saturday after hearing the news of the Biden-Harris win likely did so not only because of the extraordinary symbolism of the moment, but also because they expect policy changes to result. President-elect Joe Biden has promised to work closely with Harris, in the way he worked with President Obama, to set and push forward a legislative agenda. Public health will be at the top of the list of priorities; it is an issue that affects everyone and communities of color and women disproportionately. Biden and Harris have promised a science-based approach to the COVID-19 crisis, a response many Americans will welcome.

Harris, a former state attorney general and experienced litigator deeply familiar with what she, Biden, and a cross-racial majority of Americans have recognized as systemic racial injustice in policing, will know that this issue cries out for action.

Biden and Harris will prioritize passage of the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act. Harris undoubtedly will also promote the appointment to the federal courts of fair-minded and visibly diverse judges. Overall, I expect the vice president-elect to frame and seek solutions to problems that disproportionately affect women and communities of color in ways that promote winning legislative coalitions. Of course, the makeup and openness of Congress will largely determine the success of the Biden-Harris administration’s legislative agenda.

Frank Rich ’71

Writer at large for New York Magazine and executive producer of HBO’s “Succession” and “Veep”

As the historian Rick Perlstein observed in “Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus’’ (2001), “one of the most dramatic failures of collective discernment in the history of American journalism” followed Goldwater’s humiliating defeat in 1964. The morning-after Establishment consensus — as handed down by James Reston of The New York Times, Richard H. Rovere of The New Yorker, and the historians Arthur Schlesinger Jr., and James MacGregor Burns — posited that the conservative movement and possibly the Republican Party had been buried for good in Lyndon Johnson’s landslide. Two years later Ronald Reagan was elected governor of California, and the rest is history that culminated with the election of Donald Trump.

So we must be circumspect in assessing Trump’s legacy in the aftermath of Election Day 2020. For starters we should question a truism that has been repeated incessantly over the past four years: that Trump’s presidency, as the Times put it in an editorial in October, “has been an extended exercise in defining deviancy down — and dragging the rest of his party down with him.” The Republican Party wasn’t hijacked by Trump and dragged down to his level. Trump’s voice gave powerful expression to views that it had been harboring over the half-century since Goldwater and then Richard Nixon advanced a “Southern Strategy” pandering to white voters aggrieved by the Civil Rights Movement and other cultural shifts of the 1960s.

The “Southern Strategy” GOP is today’s GOP. The retro Republicanism of Mitt Romney and the NeverTrumpers will not make a comeback. The rising new generation of party leaders (and presidential aspirants) — Tom Cotton, Josh Hawley, Ted Cruz, Nikki Haley, Marco Rubio, Mike Pompeo — will pander to Trump’s white nationalist base just as they have for four years. Sure, they will try to sand down a few rough edges to woo back some of those “suburban housewives” Trump repelled. But that will enable them to be more insidious in both managing the MAGA constituency and furthering its objectives.

The Republicans are far more unified than the Democrats. The Supreme Court has their back. For now, Trump’s legacy endures in a movement that attracted more than 70 million voters even in defeat. The ultimate fate of Trumpism, like that of Goldwaterism before it, lies in an epic ideological battle that shows no signs of abating in our polarized and divided nation.

Michael J. Sandel

Anne T. and Robert M. Bass Professor of Government

In recent decades, the divide between winners and losers has been deepening, poisoning our politics, driving us apart. This divide is not only about the widening inequality. It is also about the changing attitudes toward success that came with it. Those who landed on top came to believe that their success was their own doing, the measure of their merit, and that those left behind had no one to blame but themselves.

This way of thinking about success was reenforced by a message embraced by Democrats and Republicans alike: “If you want to compete and win in the global economy, go to college. What you earn depends on what you learn. You can make it if you try.”

Mainstream politicians missed the insult implicit in this message: If you didn’t go to college, and if you are not flourishing in the new economy, your failure must be your fault.

It is no wonder that many working people turned against credentialed, meritocratic elites. What these elites overlooked is that most Americans (nearly two-thirds) do not have a four-year college degree. So it is folly to create an economy that makes a university diploma a necessary condition for dignified work and a decent life.

Trump tapped into the sense of humiliation felt by working people who felt looked down upon by elites. Education has become one of the deepest divides in American politics. In 2016, Trump won two-thirds (67 percent) of whites without a college degree; in 2020, he won 64 percent of this group. Although Biden emphasized his working-class roots and sympathies during the campaign, he only modestly reduced the gap among this group of voters.

To heal this divide, Biden will need to govern in a way that addresses the legitimate grievances of working people who have lost ground during the decades of globalization, who have experienced not only wage stagnation but also diminished social recognition and esteem. This means focusing less on arming people for meritocratic competition and focusing more on making life better for those who lack a diploma but who make essential contributions to our society— through the work they do, the families they raise, the communities they service. It means renewing the dignity of work and making it the central political project of the Biden presidency.

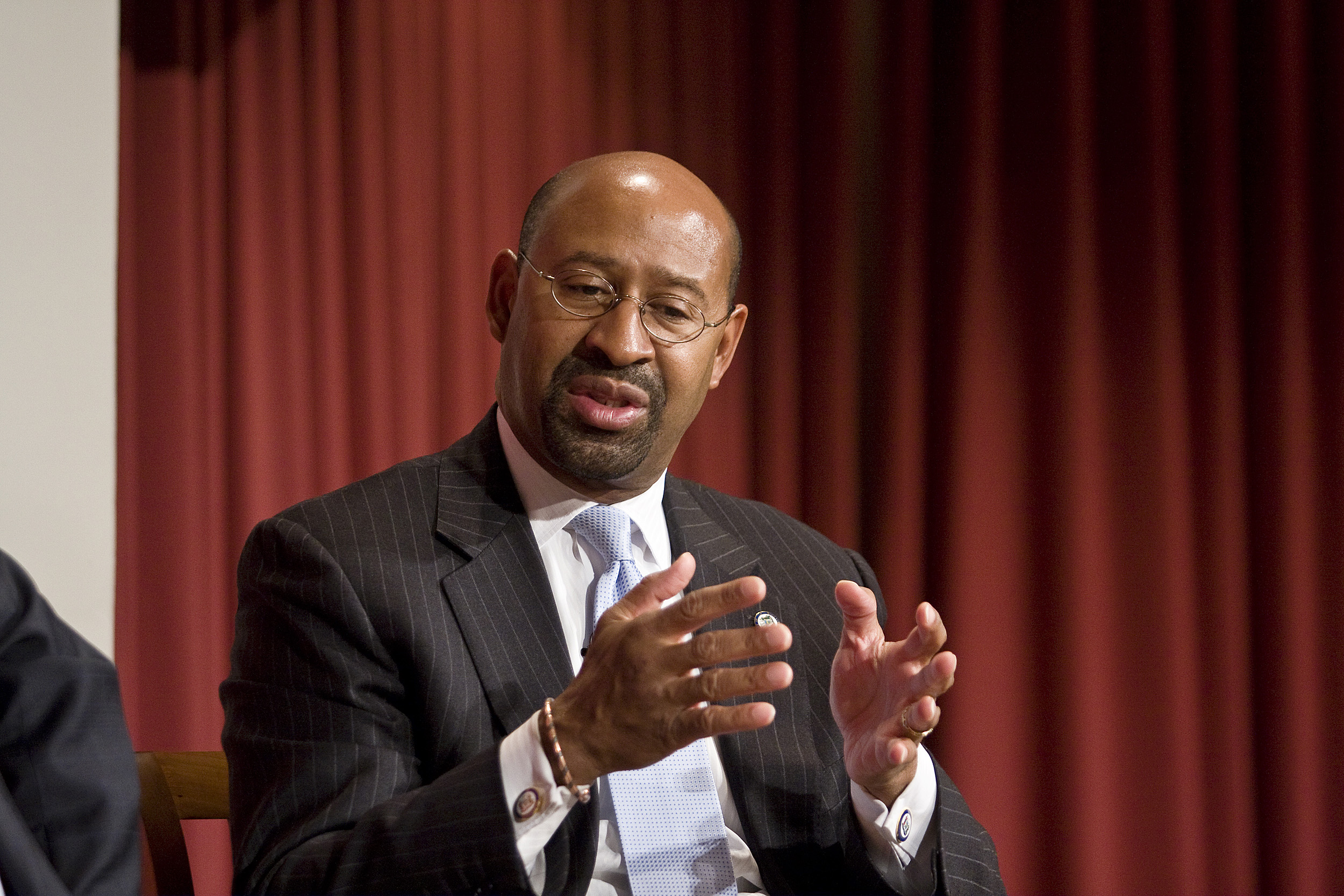

Michael Nutter

Institute of Politics, Fall 2020 Fellow, Mayor of Philadelphia, 2008-2016

To some extent, things have really played out the way many of us anticipated. We talked about the “red mirage” and “blue shift” some time back, that many Republicans would vote in person, many Democrats would use mail-in because of their concerns about COVID-19. Vice President Biden [went] up in Pennsylvania and a significant amount of that gain was because of votes right here in Philadelphia. So we’re tremendously proud. Pennsylvania, of course, is Biden’s birthplace. He spent a lot of time in Pennsylvania; he knows Pennsylvania and said at the outset that he was a person who would be able to communicate with Pennsylvania.

African Americans have been fighting — literally — in wars for the same freedoms and liberties that many white Americans have enjoyed from Day One. We had to fight with the country to be in the American Revolution, and we’ve fought in every war since for freedom, many times not enjoying those same freedoms that we were fighting for and liberating other countries to have freedoms that we didn’t have in America. So this is not a one-off. This is not one time. Black people, brown people, people of color have been saving America from itself for hundreds of years, and in many instances, saving white people from themselves in trying to make society better. Certainly, as a people, we are not perfect. No one is perfect. But we show it out, and we show up, because we understand what’s at stake. Black people get it. And so not only are we trying to save America from itself, but we’re also voting our own interest. Trump is not in our interest. Most people know that.

That was the other discernment African American voters made: It’s not about love; it’s about winning. Because as Tina Turner said, “What’s love got to do with it?” We can argue about policy; we can argue about programs, but you don’t get to have the luxury of those arguments if you don’t win. What the voters said is, “We know Joe.” And the benefit that he received, both on his own service as a senator and then being by President Obama’s side for eight years, people said, “That’s the guy. That’s the guy.” And he ran a great campaign.

With the success of Vice President Biden and Senator Harris, I’m hopeful that the 2020 race will also allow us to put a huge exclamation point at the end of 2016. As Democrats, I mean, we have got to let that race go.

Given where the country is now, how should Biden and Harris start to lead in the coming weeks and months?

Nancy Koehn

James E. Robison Professor of Business Administration

First, the country is perhaps more divided than it has been since the Civil War. If the presidential vote is a good indication, Americans disagree sharply about systemic racism, the state of our democracy, the economy, presidential decorum and norms, immigration, the United States’ place in the larger world, the seriousness of the pandemic, the threat posed by climate change, and other issues.

For many people, these disputes have become moral fault lines, spurring anger, condemnation, and even violence against their fellow Americans. This is dangerous, incendiary stuff, and it means that President-elect Biden will have to try to build bridges across these fissures — both in words and deeds. He has begun this process as a candidate, calling for bipartisan solutions for policy problems, promising to be the president not of blue or red states, but of the United States, and preaching the virtues of empathy, dignity, and compassion.

But much more will be needed to cool the country’s ideological and emotional fever and begin to heal the polity. Biden, his team, and his followers will have to learn a great deal more about the ordinary Americans — at least 70 million of them — who oppose the president-elect. We have learned, once again, that relying heavily on polling data to understand the citizenry is fraught, misleading, and damaging. Biden needs to throw out most of these tools and create new ways of listening to, getting to know and then understanding a wide swath of men and women. And he needs to develop such knowledge not only about Americans’ positions on public problems, but also about their emotional experience and in particular, the role fear plays in so many of our lives. The Biden administration should then use this awareness to govern the country, empathically and deftly, based on what we share as well as on what we disagree.

If we turn to effective crisis leaders in history — from Abraham Lincoln to the Antarctic explorer Ernest Shackleton — we see they followed some essential rules of the road. They each helped their followers get comfortable with widespread ambiguity, uncertainty, and constant change. They often navigated point to point, changing direction as the winds intensified and the waves rose. When they needed to pivot, they did so quickly, learning forward and then quickly using this new knowledge. All great crisis leaders (think New Zealand’s current Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern) also communicate frequently and regularly with their followers, thus helping them understand the state of the crisis and their roles in helping solve it. When real leaders communicate, they convey both the brutal honesty of the current challenges and the credible hope that their people can meet those difficulties. (Consider Winston Churchill’s speeches in mid-1940 with their powerful mix of Britain’s deteriorating military situation and call to unified resolve and determination.)

A final rule of the road is that how a leader frames the turbulence matters a great deal. (Remember Abraham Lincoln’s explanation of the Civil War. It began as a conflict to save the Union as it had existed since 1787, but by late 1862, the bloody fight had become a referendum on transforming the country, ending slavery, and restoring the country’s originating promise that all men are created equal.) The way a leader explains — and anchors — widespread volatility not only helps his or her followers understand the crisis much better. It also helps nurture collective resilience. We are each more likely to harness adversity for good ends — rather than, say, denying it — and to keep moving through it effectively, if we understand what it means, that we are making progress, gaining strength as we go, and that the turbulence will end.

All of this will be hard. Trying to bridge the deep divisions in the country while making swift, noticeable progress on these related crises is serious business. Add in the likelihood that congressional control will be split between Democrats and Republicans, that there is foundational work to be done restoring integrity to many branches of our national government, and that a series of global imperatives — from climate change to arms control to [a] COVID surge — demand attention, and well, Mr. Biden and Ms. Harris have their work cut out for them.

What does the victory of the Democratic ticket portend for the idea of a post-truth era?

Steven Pinker

Johnstone Family Professor of Psychology

“Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, doesn’t go away.” [Novelist] Philip K. Dick’s law was bound to collide with Trumpian alternative facts at some point, and COVID-19 was the head-on crash. Despite fears of a “post-truth era” (a claim which could never be true, because if it were true it would not be true), Trump did not have the skill or the means to turn the United States into “Gaslight,” “The Matrix,” or “1984.” Even Fox News, the closest approximation, figured out that reality could not be banished indefinitely. Biden shows all signs of realizing this, though it’s a sad commentary on the current administration that we have to give him credit for that.

What did you see with the Latinx voter turnout and particularly in key states like Florida and Arizona? What issues motivated them?

Jorge L. Vasquez Jr.

Institute of Politics Fall 2020 Fellow, Director of the Advancement Project’s Power and Democracy Program, and chair of the Hispanic National Bar Association voting rights section

Florida [was] called by the Associated Press in favor of Trump and that shouldn’t be a surprise because the Latinx community isn’t monolithic. There is a significant population of Latinx voters who are from Cuba and Venezuela and which, for one reason or another, have led them to vote for Trump. So I don’t think anyone within the Latinx community is surprised about that.

What people are surprised about is Arizona, Maricopa County, the same county where President Trump pardoned Sheriff Joe Arpaio who was found criminally liable for his abuse and disregard of the Latinx community. It made individuals recognize how something like the presidency could be a local issue, and in a place like Maricopa County, where there is a significant Latinx population that didn’t participate [up to its electoral] potential in 2016. What we see in 2020 is higher voter turnout. The Latinx population organized against the Trump administration. One of the main reasons was his rhetoric, but also his pardon of Arpaio.

Wisconsin has a significant Latinx population, and particularly a large Puerto Rican population, and it’s likely that Wisconsin went for Biden because of Puerto Rican support for him there. Or it could also be the Trump administration’s lack of response to Puerto Rico, FEMA’s lack of response after Hurricane Maria, the Census Bureau’s lack of enumerating in Puerto Rico during the Census. So there’s a whole bunch of moving pieces going on at once.

One of the things that I’m hearing on the ground and through reports that I am reading is that young voters and particularly young voters of color, have three priorities: One is racial justice; the second is police reform; and the third is COVID. What we’re seeing is Latinx voters care about those three issues, that they are showing up to the polls. We know COVID-19 was a huge factor and that a significant amount of that population voted by mail this year. So until we see data, it’s hard to really know [how many voted].

What it’s going to tell me is that the Latinx community is looking to maximize its political power. For the first time, there were 32 million eligible Latinx voters. Many of those Latinx voters are Gen Z’s and Millennials, and it’s not coincidental that in 2020 we’ve seen an influx of Gen Z and Millennial voters. And I think in part, a large part of that has contributed to the Latinx voters taking democracy seriously and making sure that they participate.

On foreign policy

How were the election results received globally?

Nicholas Burns

Roy and Barbara Goodman Family Professor of the Practice of Diplomacy and International Relations

The international reaction to Joe Biden and Kamala Harris’ victory over Donald Trump has been electrifying and revealing.

Just after Biden’s victory was announced on Saturday, bells pealed in Paris and in Berlin where the “Freiheitsglocke” (the Freedom Bell) rang out. America’s closest allies from Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to Germany’s Angela Merkel, France’s Emmanuel Macron, and beyond were quick to issue warm and welcoming congratulatory messages.

My wife, Libby, and I have two daughters living overseas in Berlin and Buenos Aires. Both sent photos of front-page headlines proclaiming Biden’s victory. My own Harvard email address filled with countless messages from foreign friends in what seemed a collective global sigh of relief over the outcome of the Nov. 3 vote. They too had a stake in our election.

They hope Biden’s America will be back at the global leadership table — the World Health Organization on the pandemic, the G-20 on the global recession, the Paris Agreement on Climate Change.

Europeans and Canadians understand NATO cannot succeed without purposeful and positive American leadership. Our allies Japan, South Korea, Australia, and strategic partner India need America by their side. Our many friends in Africa look for a more engaged America on their continent. Mexicans, Brazilians, Argentinians, and others in the Americas need a U.S. leader committed to our common future.

Some see Biden’s win as a blow against populism in the U.S. and in those parts of the world, particularly in Europe, where it poses a threat to democratic rule. Millions around the world are counting on the new administration to be a vocal advocate for democracy and freedom in areas where President Trump has been inexcusably silent — Hong Kong, the Uyghurs, North Korea, Belarus, Russia.

The Constitution gives the president considerable power in foreign policy. Biden will take office as one of our most experienced presidents in foreign and defense policy. Let’s hope for bipartisan support on some of the most difficult challenges — strengthening NATO, re-engaging with the European Union, opposing Russian and Chinese troublemaking.

The impact of Biden’s election, of course, will be felt most strongly at home in reaffirming the core principles of American democracy — the rule of law, the sanctity of the vote, and the peaceful transfer of power.

It’s a new day in America and around the world. A time of hope.

On health care

If the Trump administration keeps its current path, where will the world be, with respect to global health by inauguration day Jan. 20?

Paul Farmer

Kolokotrones University Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine and chair of the Harvard Medical School Department of Global Health and Social Medicine and co-founder of the global nonprofit Partners In Health

We will be in more dire straits than four years ago. I don’t believe that global health, and still less global health equity, has been a major concern of the Trump administration, and COVID has made this disinterest dramatic — the United States is on the globe, too. This administration has waged war against the World Health Organization, tried to neuter or mute the Centers for Disease Control, tried to undo Obamacare, and attacked internationally (and nationally) admired figures like [Director of National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases] Tony Fauci. Fauci is widely deemed to have done more than any other U.S. official to save lives in Africa, and my colleagues across that continent and on this one, have asked me again and again what Trump has against health equity and people like Fauci. It’s been a hard question to answer.

How would you advise a Biden administration to shift the U.S.’ approach to the COVID pandemic nationally and globally?

I would advise a Biden administration to acknowledge that the ranking threat to sustaining and growing gains made over the past few decades, and probably forever, has been underinvestment in building stronger public health systems, which require stronger safety nets and the staff, stuff, space, and systems for the job. Again, this is as true of the United States as it is of the far poorer countries in which I’ve also worked. Some of these, including Rwanda, have done better than the U.S.A. in terms of COVID response. We will have years of debate about why this came to pass, or whether or not it will hold, but it’s pretty clear that having a national and public backbone for a health system, and having community health workers — who are usually the folks who do contact tracing, for example, and serve as living links between hospitals, clinics, and households — are two important lessons to draw from places like Rwanda. There are others, and my colleagues there often note that several of their most successful programs, including Bush-era ones that brought AIDS under control, have been supported by American largesse.

Fortunately, the Biden campaign, and now his transition team, includes folks with experience in the fight for health equity, some with Harvard ties, and are aware that global health equity is a nonpartisan issue. It seems unlikely that a Biden-Harris administration would retreat from the bold policies and outward-looking that might help bring COVID under control. That won’t happen without increased commitments to global health.

On immigration

How will President-elect Biden change immigration policy?

Philip L. Torrey

Director, Crimmigration Clinic, Managing Attorney, Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, Harvard Law School

The election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris is obviously incredibly historic. I’m hopeful that it will usher in a new era of immigration reform. There are a lot of policies that Biden can implement immediately upon taking office. For example, he can revoke a number of the horrific executive orders signed by President Trump, including orders that have targeted Muslims, Dreamers, and individuals seeking humanitarian protection at our country’s southwestern border.

Biden can also take measures to improve the fairness of our immigration system like reforming the Board of Immigration Appeals and providing immigration judges with greater independence. I will be especially interested to see if Biden takes steps to end our broken immigration detention system. He can begin by severing our country’s reliance on the for-profit prison industry.

On the economy

What does a Biden win mean for the economy, especially in regards to COVID, and what’s likely to change going forward and how?

Kenneth Rogoff

More like this

Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Professor of Economics

The most urgent issue for the incoming Biden administration is to implement a national policy on dealing with the pandemic, one that tries to strike a better and (much) more consistent balance between more extensive testing, better treatment, and social distancing restrictions, at least until an effective vaccine can be widely implemented. Another major round of catastrophe relief spending will be welcome, but it is also important to have a longer-term plan involving refurbishing and improving the nation’s infrastructure broadly defined, for example including a program to provide universal basic internet service.

Responses were gently edited for clarity and length.

— Alvin Powell, Christina Pazzanese, Colleen Walsh, Juan Siliezar, and Liz Mineo