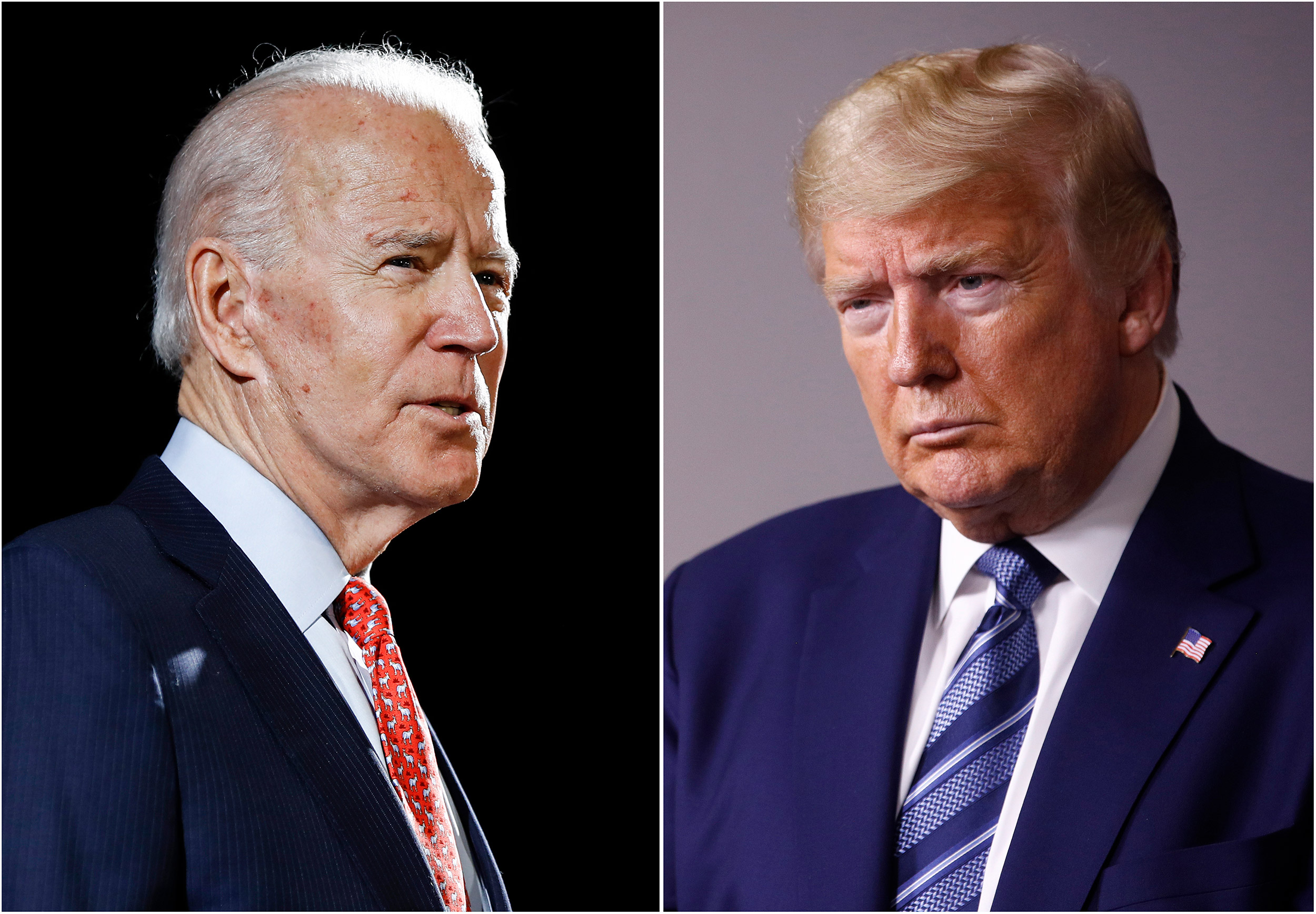

President Trump (right) and former Vice President Joe Biden debate for the first time Tuesday.

AP Photo/File

Will Tuesday’s presidential debate change the course of the election?

Political analysts and debate champs offer tips on what to look for

The presidential race enters its final phase as President Trump and former Vice President Joe Biden debate for the first time Tuesday night, with voting already underway across the country and polls showing few undecided voters left. Often billed as pivotal, momentum-changing events for the perceived winners and losers, presidential debates can end up being more spectacle than spotlight, and tend to be remembered more for candidate zingers and missteps than for significantly changing voter opinion. The Gazette asked some political analysts and debating champions to discuss what Biden and Trump will need to accomplish Tuesday and what pitfalls they’ll need to avoid to have a good night, and whether the showdown will likely have any real effect on election results.

What are the most important things Biden and Trump each need to do — and not do — in this debate?

David Gergen, J.D. ’67

Former White House adviser to Presidents Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, Ronald Reagan, and Bill Clinton

Professor of Public Service and founding director of the Center for Public Leadership, Harvard Kennedy School

Typically, a front-runner like Joe Biden has still had three major hurdles to clear before the elections: a strong vice-presidential choice, a successful convention, and a winning performance in the opening presidential debate. Biden has cleared the first two with ease. If he now walks away with a winning debate, he will be nearly unstoppable and could put the Senate over the top.

One of the most interesting aspects of this campaign is how steadily Biden has commanded a lead of roughly six to seven points. In a two-man race, voter approval for Trump has been hovering way down around 40 percent of likely voters. Some 90 percent or more of voters say they have already made up their minds. And so far, Trump hasn’t come up with a winning message. Indeed, the latest bombshell about his minuscule tax payments has only deepened a public sense that he is a fraud. All of this is bad news for Trump, and he has precious little time to turn things around.

So, then, what is the best strategy for Biden? First and foremost, he has to emerge as a credible, energetic president. He needs to convince people he is a healer who will work with all sides in pursuit of the common good, and he will restore American leadership. He needs to lay out a broad overview of his policies without getting into the weeds. His answers have to be firm and crisp and still preserve his strongest asset: his humanity. Like Ronald Reagan of yore, he ought to turn aside Trump’s vicious assaults with humor and dignity.

Bottom line: Biden enters this debate holding most of the high cards. Now he just has to play them well.

Which debating techniques best suit each candidate and which traps should they lay for the other?

Asher Spector ’21 and Aditya Dhar ’21

Harvard College Debating Union

Spector is the 2019 North American champion in British Parliamentary debate

Dhar is on the reigning top-ranked U.S. team in American parliamentary debate

Trump has historically been aggressive, bold, and inflammatory. He tries to throw his opponent off with a barrage of ad hominem attacks, false claims, and inappropriate comments. This strategy — although unconventional — was surprisingly effective in 2016: He dominated the Republican primary and held his own against veteran debater Hillary Clinton.

We think there are a few ways Biden can slow Trump’s momentum. First, he can goad Trump into lying about the pandemic and the state of the country. Trump likes to heap exuberant praise on his work in office, especially when someone casts doubt on his record. We think voters know better. When Trump pretends everything is fine, he seems out of touch.

Second, Trump is himself making a mistake by attacking Biden’s mental agility. Repeated attacks on Biden’s mental competence and spurious rumors about dementia have set expectations for his performance low. If Biden holds his own, voters may count that as a win. Similarly, we think that any stumbles on Biden’s part will seem less newsworthy, because people already see him as gaffe-prone.

But not all attacks are baseless. While Biden’s 2012 debate performance against Paul Ryan was widely celebrated, there are real concerns that Biden isn’t as quick on his feet as he used to be. Trump’s aggressiveness is a strength here — he will put Biden under sustained pressure in order to make Biden look old, confused, and unfit to lead.

Moreover, while Trump’s base is unified and loyal, Biden has to appeal to a wide coalition of voters. So Trump can use the debate to force Biden to explicitly delineate his stances on a series of issues — the Green New Deal, Medicare for all, court packing, and recent protests — and, in doing so, create friction between the different factions Biden needs to rally.

Recent polling shows white support for Black Lives Matter protests declining, a trend that favors Trump. If police violence and the need for police reform has become a subject that could hurt Biden, can Biden address this issue in a way that satisfies Black voters and their allies, but also reassures those who have lost support for the protests?

Yanilda María González

Assistant Professor of Public Policy, Harvard Kennedy School

The consensus that saw 74 percent of Americans supporting Black Lives Matter protests and 69 percent acknowledging a broader problem in police treatment of Black Americans has given way to the fragmentation that typically characterizes attitudes toward policing and race, with stark divisions along racial and partisan lines. This fragmentation in societal attitudes toward policing presents Joe Biden with a common dilemma facing center-left and leftist political leaders throughout the Americas: finding the balance between societal demands for police reform and calls for “law and order.” President Donald Trump, meanwhile, has staked out a clear “law and order” position, explicitly stating that he expects unconditional support [from] law enforcement to gain him the electoral support needed to win in the upcoming elections. The crucial question for Biden will be whether to maintain police reform as central to his campaign platform or rebuff demands for greater restrictions on policing that are popular among the Democratic base in order to appeal to so-called swing voters.

A look to U.S. history and the experiences of similarly situated leaders in other countries suggests Biden may be more likely to opt for the latter. President Lyndon Johnson pushed a “war on crime” in 1965, in response to Barry Goldwater’s concerted “law and order” campaign against the Civil Rights Movement during the 1964 elections. New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio came to office denouncing racially biased policing and vowing to enact reforms, only to cower in the face of police pressure. Similarly, Mexico’s current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, back when he was the leftist mayor of Mexico City, advanced not police reform but a zero-tolerance policy championed by Rudy Giuliani. By the same token, police reform stalled in Brazil under leftist presidents Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and Dilma Rousseff. Throughout the Americas, right-wing parties and candidates have found electoral success with “tough on crime” messages to increase police power and budgets, while policing has remained an Achilles’ heel for left and center-left politicians, who have largely fumbled in their efforts to build sustained societal consensus favoring police reform. The key factor for Biden may be whether the momentum of the largest protest movement in U.S. history will impose an electoral cost for failing to enact police reforms.

Trump and Biden have very different speaking styles. As they try to persuade and motivate voters, what should they both keep in mind from a marketing communications standpoint?

Alison Wood Brooks

O’Brien Associate Professor of Business Administration, Harvard Business School

Navigating disagreements and differences in conversation, especially with the goal to persuade, is a difficult task. Some breakthrough recent research using natural language processing (NLP) of real disagreement conversations at scale reveals some elements that make conversations less likely to end in hostile blow-ups and more likely to end with changed minds and healthy ongoing relationships. These elements include using respectful language (e.g. no name-calling), actively acknowledging and clarifying the other perspective (“Am I right that you are saying…”), asking follow-up questions, highlighting areas of agreement no matter how small or obvious, hedging your claims (“I think…”) rather than stating them as facts, phrasing arguments in positive versus negative terms (“It’s helpful to…” versus “You should not…”), avoiding explanatory words like “because” and “therefore,” and dividing yourself into multiple selves (“I agree, but part of me wonders if…”).

Early evidence suggests that the 3 R’s of conversational kindness—respectful, receptive, responsive—are learnable, and everyone would do well to hone these conversational skills, including both Biden and Trump. Surprisingly, achieving these aspirations make our messages more persuasive. But, importantly, the presidential debate is not a one-on-one conversation. It is political theater with a massive audience—under the guise of a dyadic exchange. What works well to navigate conflict in private may or may not work with such a large audience. If their primary goal is to win over hearts and minds, then I suspect that even in the strange, high-stakes arena of public presidential debate, the candidates would do well to abide by the 3 R’s—be respectful, receptive, responsive. My hypothesis is testable: If we run the debate transcript through our NLP detectors after the fact, how would Biden and Trump score? And will their conversational performance scores align with public perceptions and approval ratings? I’d love to find out.

With so few undecided voters left, can the debates shape the race in any significant way?

Thomas E. Patterson

Bradlee Professor of Government and the Press, Harvard Kennedy School

Like earlier ones, the 2020 debates are a key moment in which voters engage the campaign more fully than at other times. More than 80 million viewers watched one of the Trump-Clinton debates in 2016, an audience level that is beyond anything but the Super Bowl. Yet, the history of presidential debates tells us that they rarely upend a race. Most voters will have already made up their minds about the candidates. In fact, judging from the polls, the number of decided voters is higher than normal this year. Selective perception — seeing what they want to see in Biden and Trump — will govern how the great majority of viewers will judge the upcoming debate. In the past, even weak performances have dislodged few votes. Debates are best seen as a special opportunity for voters to listen to the candidates, but not as a time when voters come with an open mind with the intent of determining which of the contenders has the traits desired in a president.