Artist’s conception of a potential solar companion, which theorists believe was developed in the sun’s birth cluster and later lost.

Illustration by M. Weiss

Far-out findings from the cosmos

Harvard astronomers research twin suns, a sneezing star, and ‘Oumuamua

It was a busy summer for scientists at the Center for Astrophysics | Harvard & Smithsonian. Researchers put forth a theory that indirectly nods to a famous “Star Wars” scene, resolved one mystery about the solar system’s first known interstellar visitor, and showed that a star can sort of “sneeze.” We caught up with them and asked about these far-out findings.

A long time ago but not so far, far away

It was an unforgettable scene in the first “Star Wars” movie: Young Luke, eager for adventure, storms out his house after fighting with his uncle about having to spend another year stuck at home. Outside he gazes up at the fiery twin suns of the planet Tatooine as they slide toward the horizon, John Williams’ “The Force Theme” rising in the background.

While a new study from a pair of Harvard astronomers may not have the same visual power, it does reveal that a similar view of binary suns may have existed in our very own solar system roughly 4 billion years ago.

In The Astrophysical Journal Letters, Avi Loeb, Frank B. Baird Jr. Professor of Science at Harvard, and Amir Siraj ’21, an astrophysics concentrator, theorize that the solar system originally had two suns instead of one, and if true that could have far-reaching implications for the origins of a dense cloud that surrounds the system and a possible ninth planet.

First, a little info on the sun’s long-lost twin: Loeb and Siraj think it had the same mass as its companion and was formed alongside it when the solar system began, but was situated 1,000 times farther from the Earth than our own sun. As to its fate, the two researchers believe it drifted away well before the Earth formed.

“The binary companion was [most likely] freed by the gravitational influence of a passing star in the sun’s dense birth environment,” Siraj said. “It could now be anywhere in the Milky Way galaxy.”

Siraj and Loeb aren’t the first to theorize a two-star start to the solar system. In fact, most stars are born with companions. But Siraj and Loeb’s theory could help explain the formation of the Oort cloud — the sprawling sphere of debris that sits at the edge of the system and surrounds it.

Many astronomers believe the Oort cloud formed with leftover chunks of rock and ice from our solar system and neighboring ones. Siraj and Loeb say their two-sun theory could account for why the cloud is as dense as it is, since binary systems are far better at pulling in and capturing these types of objects than single-star systems.

Such a system could also help explain the existence of a potential ninth planet that astronomers believe is out there — an undisputed one this time (no offense, Pluto). Their model supports the theory that this ninth planet was captured into the system, meaning it didn’t form here.

The ‘Oumuamua debate continues

The mystery surrounding our solar system’s first known interstellar visitor deepened after astronomers ruled out a major explanation in a new paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

The study rebuts a theory published earlier this year that suggests the object, dubbed ‘Oumuamua from the Hawaiian for scout, was a cosmic iceberg made of frozen hydrogen. Co-authored by Loeb, the paper concluded this is likely not the case because, if it was, the object wouldn’t have been able to make the journey intact. The scientists argue it would quickly melt or break apart when it passed close to a star. ‘Oumuamua didn’t even flinch when it passed the sun.

The astronomers also looked at what it would take to form a hydrogen iceberg the size of ‘Oumuamua, and where it could have originated. They focused on one of the closest giant molecular clouds to Earth (only 17,000 light-years away). They found the environment there too inhospitable for iceberg formation — and so far away that it would be highly unlikely that it could have survived the journey, even if it somehow managed to form.

The debate around ‘Oumuamua started in 2017, when it was first discovered by observers at the Haleakalā Observatory on the island of Maui in Hawaii. Among other theories, it has been hypothesized to be an interstellar asteroid, a comet, and even an alien artifact — Loeb himself suggested this in 2018 and has put out a body of work on the topic. He has a book on ‘Oumuamua, “Extraterrestrial,” due out early next year.

All of this is to say that the truth on ‘Oumuamua is still out there, but perhaps it won’t be a mystery for long.

“If ‘Oumuamua is a member of a population of similar objects on random trajectories, then the [new] Vera Rubin Observatory, which is scheduled to [be operational] next year, should detect roughly one ‘Oumuamua-like object per month,” Loeb said. “We will all wait with anticipation to see what it will find.”

Gesundheit … to a star?

Betelgeuse, the 10th-brightest star in the night sky and the second-brightest in the Orion constellation, mysteriously dimmed toward the end of 2019. By February 2020, the star had lost more than two-thirds of its brilliance. It was a change so noticeable that observers on Earth could see it with the naked eye. Many thought the old star was finally dying and would go supernova. Then it suddenly started regaining its brightness. By April, in fact, it was restored. So what happened?

Put simply, Betelgeuse kind of sneezed.

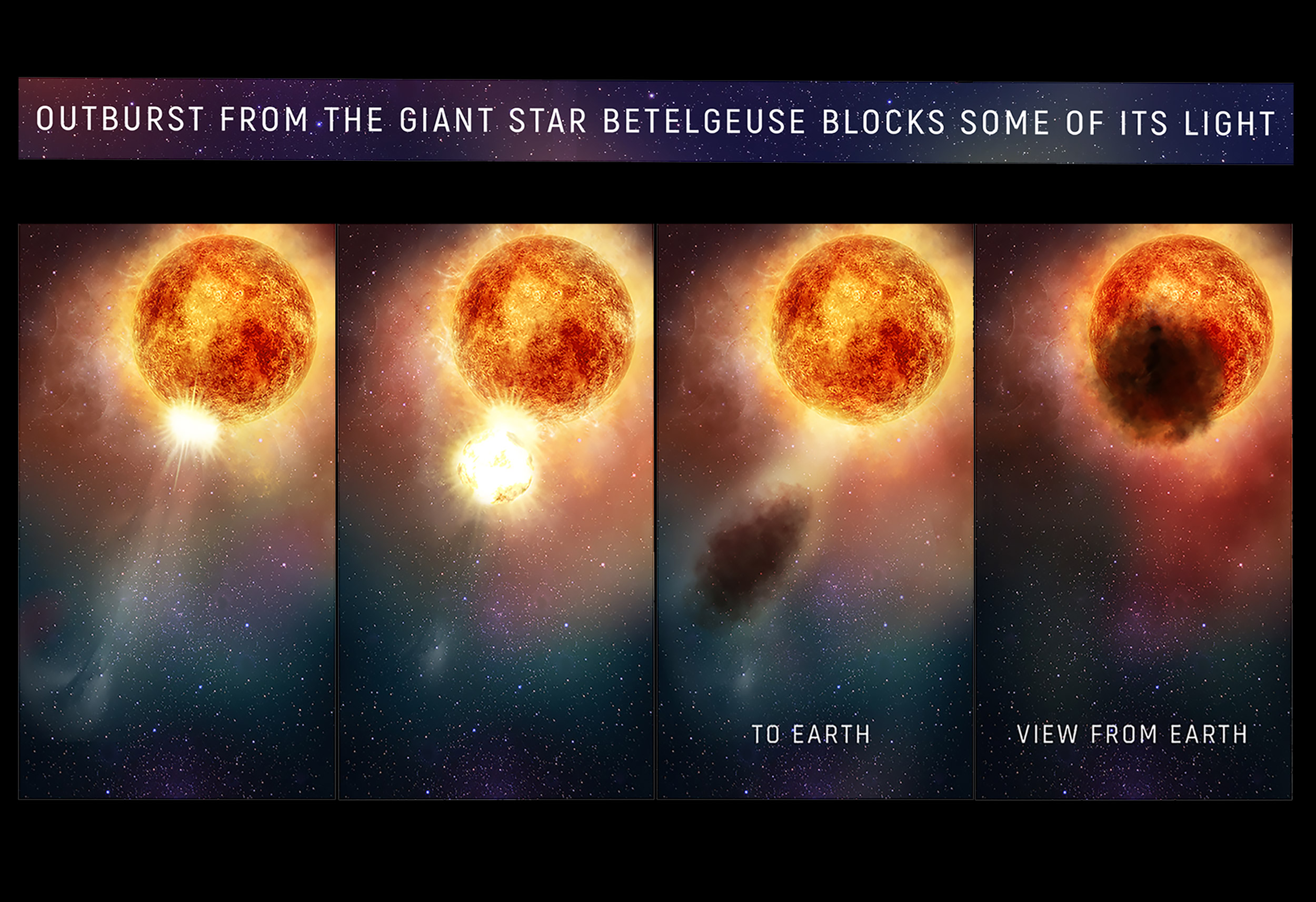

In the first two panels a bright, hot blob of plasma is ejected from the emergence of a huge convection cell on Betelgeuse’s surface. In panel three, gas rapidly expands outward, cooling to form an enormous cloud of obscuring dust grains. The final panel reveals the huge dust cloud blocking the light (as seen from Earth) from a quarter of the star’s surface.

Credit: NASA, ESA, and E. Wheatley (STScI)

This is the explanation a team of international astronomers led by Andrea Dupree, the CfA’s associate director, published in a paper in Astrophysical Journal.

Looking at recent observation data, researchers believe the dimming periods were most likely caused by the ejection and cooling of dense, hot gases. Between October and November 2019, data and images gathered by the Hubble Space Telescope showed intense, heated material moving out of the star’s extended atmosphere at 200,000 miles per hour. They believe this mass formed a soot-like dust cloud when it cooled that blocked the southern part of the star, accounting for its dimming in January and February.

While researchers think they can account partially for the anomaly, they have other questions. They can’t, for example, determine how the outburst started or why, nor do they know why the star is losing mass at an exceedingly high rate.

What they do know is that Betelgeuse dims every 420 days. But new observations between late June and early August of this year show it’s off schedule. The star is dimming roughly 300 days earlier than expected. Yet another new mystery.

Researchers also believe Betelgeuse is nearing the end of its life and eventually will go supernova. In fact, it might have happened already, and we just haven’t seen it yet.

“Betelgeuse is so far away, it takes about 750 years for the light to reach us on Earth,” Dupree said. “So, the light from Betelgeuse [we saw] left the star at about 1270 A.D. here on Earth.”