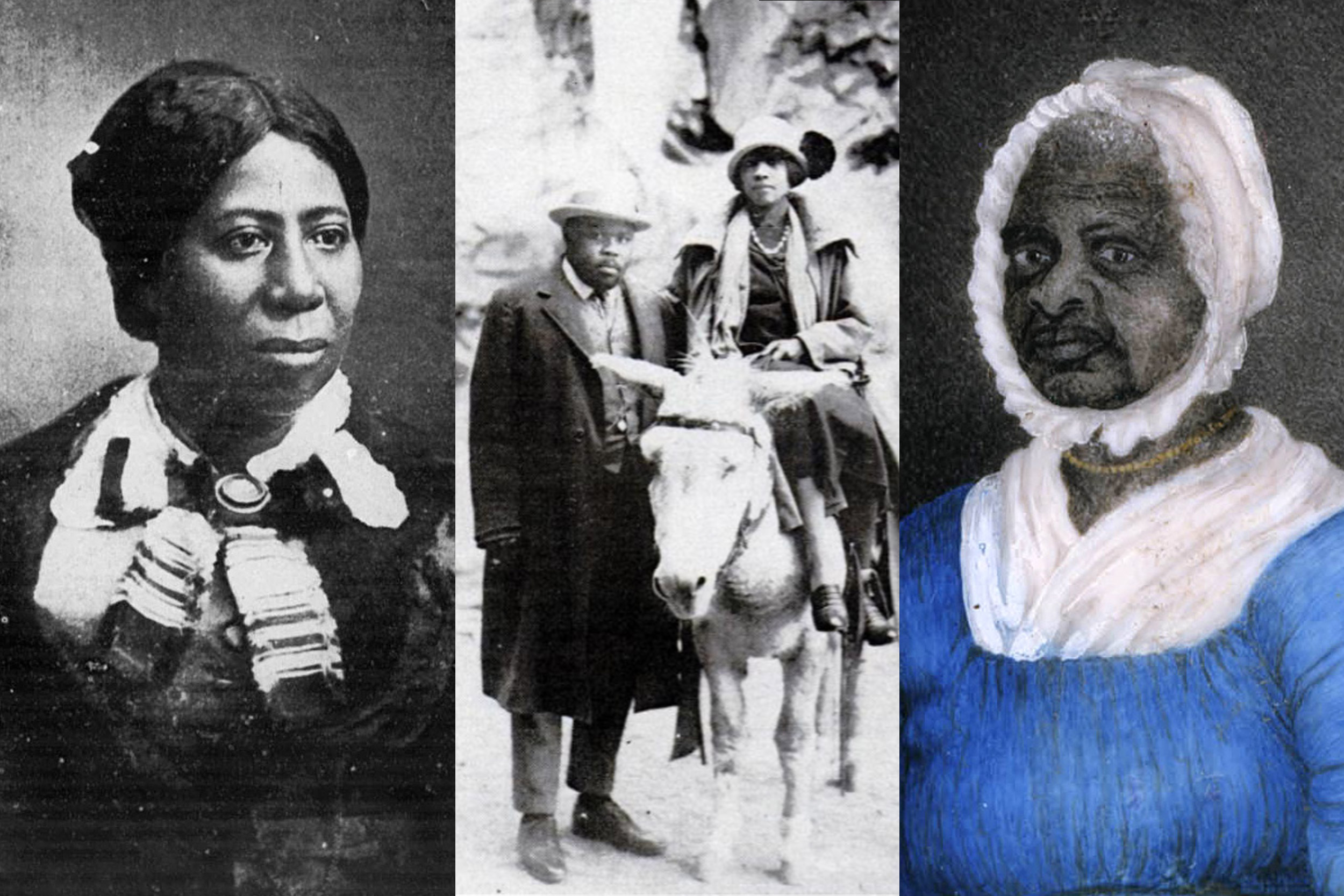

Historic figures who played prominent roles in the fight for equality: Anna Murray-Douglass (ca. 1860) (from left), Marcus Garvey with Amy Jacques Garvey (1922), and Elizabeth Freeman (1812).

Source: All images Wikipedia/Public Domain; Freeman photo courtesy of Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston

Defining a centennial

Panel discusses what happened in the years before Black women actually got the vote

When the 19th Amendment was ratified 100 years ago, it granted all women the right to vote — in theory. In reality, most Black women didn’t gain suffrage until the Voting Rights Act of 1965; during the intervening 45 years, they were stymied by poll taxes, literacy tests and other racist measures.

The question of whether or not this anniversary can be called a celebration was amicably discussed in the virtual panel “100 Years of Suffrage: 45 Years of Waiting” on Aug. 13. The talk, a city event co-sponsored by city councilor and former Cambridge Mayor E. Denise Simmons and the Cambridge YWCA, included Kenvi Phillips, the first curator for race and ethnicity at the Radcliffe Institute’s Schlesinger Library.

Simmons proposed that it might be more fitting to “commemorate” the anniversary than to “celebrate” it; instead of “glorifying … the small victories,” she said, it might be better to contextualize them and “look at the history, the truth right before you.”

Phillips, however, made the case for “celebrate,” as Black women “celebrate one another … protect one another, embrace one another.”

“It’s a milestone, and it is something that a lot of people do celebrate, but it has an underbelly, and that’s what we have come to understand. … There is this invisibility of Black women in history,” summarized Charlotte Golar Richie, senior vice president for public policy, advocacy, and government relations for YouthBuild USA.

The discussion was introduced by Rep. Ayanna Pressley, who praised the “determined activism” that led to the passage of the 19th Amendment, while noting that Black women’s struggle for voting rights is linked intrinsically to “the struggle to rectify the legacy of systemic racism and institutionalized oppression.”

The conversation touched on the often-overlooked histories of Black women who fought for both racial and gender equality, before and after the passage of the 19th Amendment. Some of them were overshadowed by the men they supported, in particular, Anna Murray-Douglass, who was largely responsible for her husband Frederick’s journey to freedom, and Amy Jacques Garvey, the second wife of Marcus Garvey, who was a driving force behind his political movements. Elizabeth Freeman fought for equality while the international slave trade thrived in America: In 1781, she sued for her freedom and won, setting a legal precedent for the end of slavery in Massachusetts. Some, such as Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman, advocated for intersectional equality in a time when many prominent suffragists were white supremacists. Others, such as Fannie Lou Hamer, Rosa Parks, Jo Ann Robinson, and Ella Baker, were instrumental in the Civil Rights Movement, the Montgomery bus boycott, and the push to pass the Voting Rights Act. Phillips also mentioned Mary McLeod Bethune, who, among other achievements, founded a college and a hospital in Daytona Beach, Fla., and refused to be intimidated by the Ku Klux Klan.

YWCA Cambridge Director Eva Martin Blythe told a story about suffragist, anti-lynching advocate, and NAACP founder Ida B. Wells: In 1913, Wells was told that Black suffragettes could march only at the back of the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. Wells refused, and marched with the white women in her state’s delegation. Blythe compared Wells’ fight to the enduring struggle for equality: “We continue to say we are not going to be second-class citizens; we are not going to be mistreated; we are not going to be looked at as ‘lesser than.’”

Wilnelia Rivera, founder of Rivera Consulting, agreed, saying that as Americans, “We’re constantly trying to redistribute power in a way that actually is reflective of who we’re supposed to be. And yet, after 400 years … somehow Black women have to wait.”

Phillips suggested that the answer to what we need to do is to look at what we’ve already done. Black women have shown they can organize, work through differences and “galvanize [their] ideas.”

“We’ll make our own space. … We’ll come up with our own organization and have our own political power,” she said.

“The power of the people is far greater than the people in power,” the Rev. Irene Monroe, an activist and syndicated columnist, added.

In her closing remarks, Suffolk County District Attorney Rachael Rollins reminded the panel that “History is written by the winners.”

But “We are winners,” Rollins said of Black women. “Clearly, we are exceptional. But we need to start rewriting history.”

Cambridge School Committee vice chair Manikka Bowman was also among the panelists.