This year, a single digitization focus at Houghton

Library pauses other work for ‘Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom’

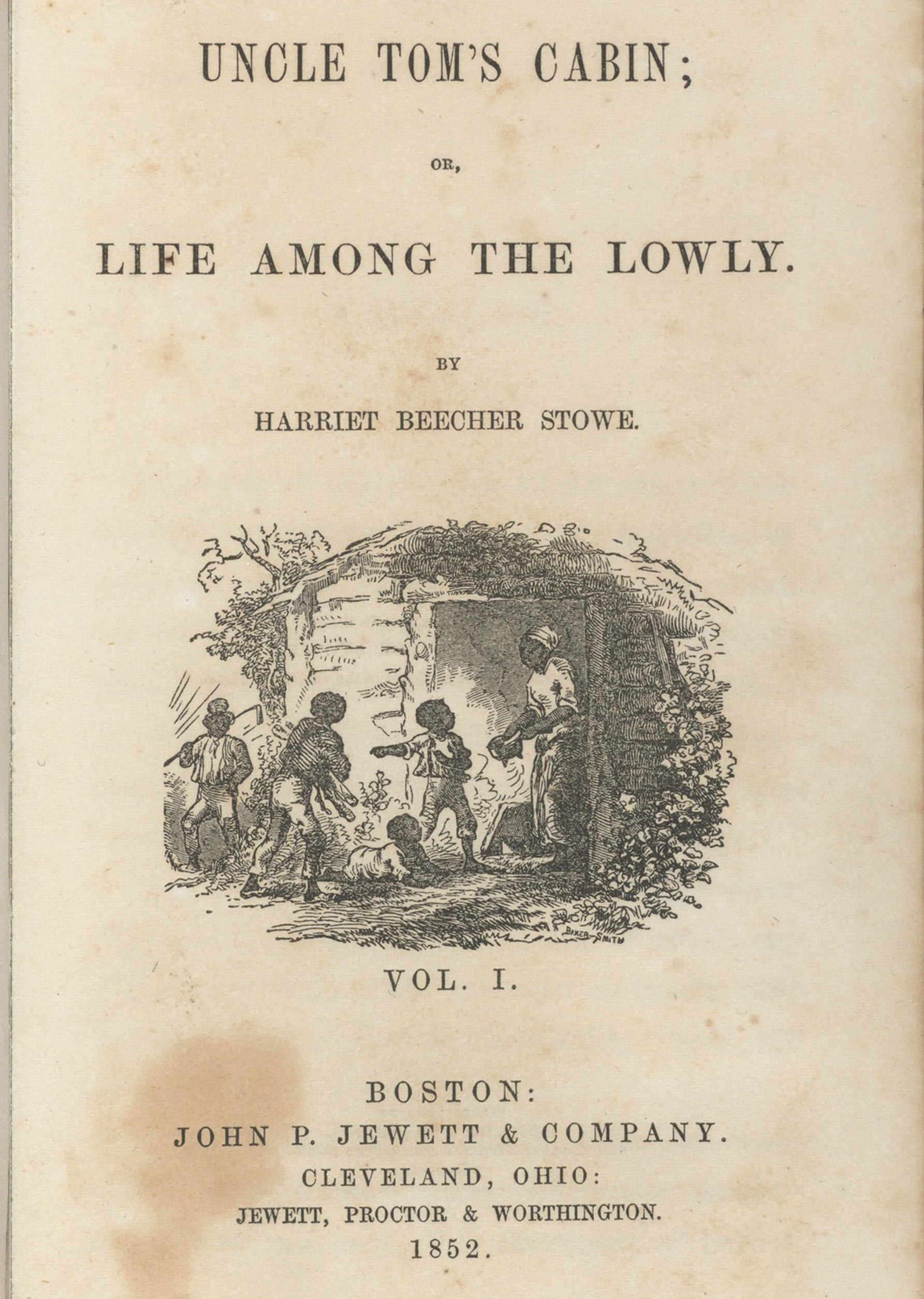

The digitized title page from a first edition of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” by Harriet Beecher Stowe (1851).

Photos by Dorothy Berry/Houghton Library

As technology has evolved over the last 10 years, Houghton Library has digitized many of its rare treasures and made them freely available online. But while users can find Emily Dickinson’s poetry or Theodore Roosevelt’s family photographs on the library website, letters from Frederick Douglass or Sojourner Truth still require a trip to the Houghton Reading Room and a request to view the originals.

This year, that will change.

For the 2020‒21 academic year, Houghton will pause all digital projects to focus solely on building a digital collection related to Black American history. Digital Collections Program Manager Dorothy Berry will lead a team in digitizing and making discoverable thousands of materials for the online collection, called “Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom: Primary Sources from Houghton Library.”

“We’ve always had these materials, but now we need to be proactive about access and accessibility,” Berry said. “Making these materials accessible and showing we value them is a way of redressing a field that has historically not been welcoming to African Americans.”

Her team’s primary focus will be 2,000-plus pamphlets and ephemera from the late 1700s through the early 1900s, by both Black and white creators. The items range from bills of sale for enslaved Black people to letters from abolitionists, but they all capture public discourse on Black lives.

Thomas Hyry, Florence Fearrington Librarian of Houghton Library, said the materials aren’t just historical artifacts — they’re directly related to American life today.

The work to digitize the materials and make them accessible “helps place the current movement for racial justice into historical context,” Hyry said. “It promotes greater understanding of the roots of systemic racism and efforts to fight it.”

Berry noted that the project does not encompass everything Houghton holds related to African American history or Black people. She wanted to start with materials that would lend themselves to a digital collection with a common theme. Though she doesn’t anticipate completing digitization of these materials in one year, Berry does expect to make meaningful progress.

Houghton will still fulfill users’ digitization requests during this year, including materials for Harvard courses. But the typical process of accepting project proposals from staff members will not take place.

Hyry said making space for this work is a move that’s long overdue.

“When Dorothy proposed the ‘Slavery, Abolition, Emancipation, and Freedom’ project, we were forced to reckon with the fact that we had not previously made digitizing these collections a priority,” he said. Now it has become one, in part as a way of acknowledging and correcting past mistakes.

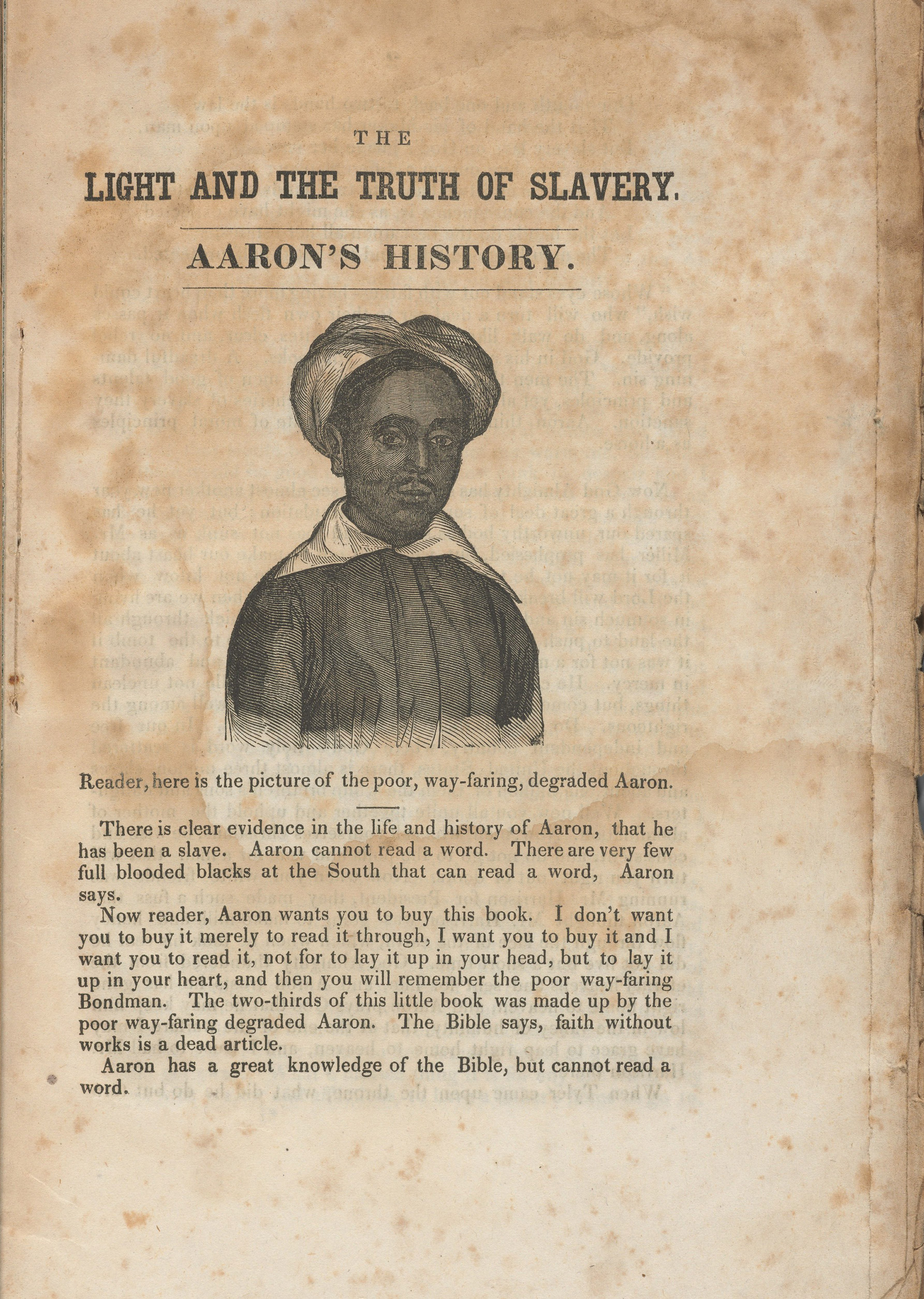

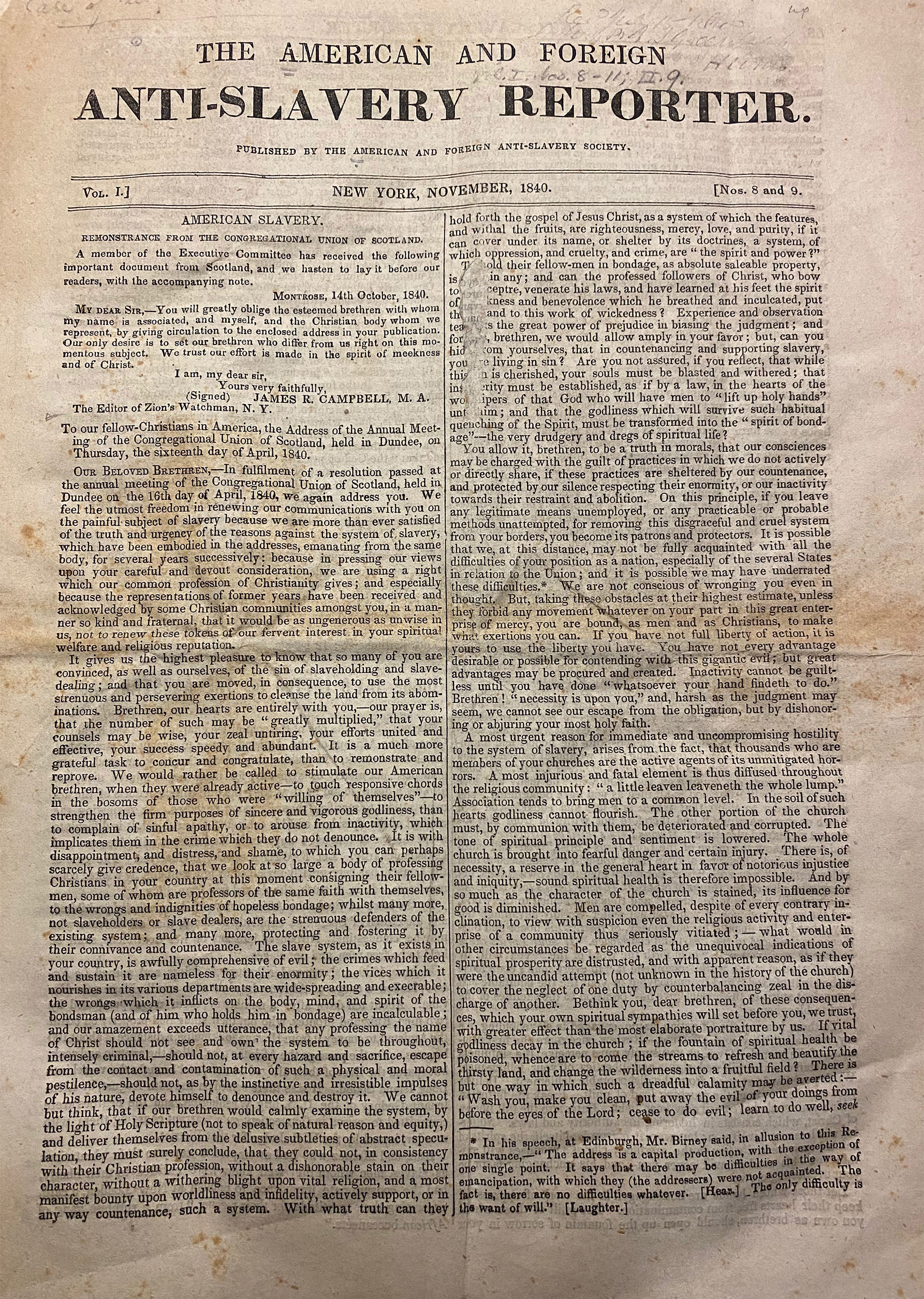

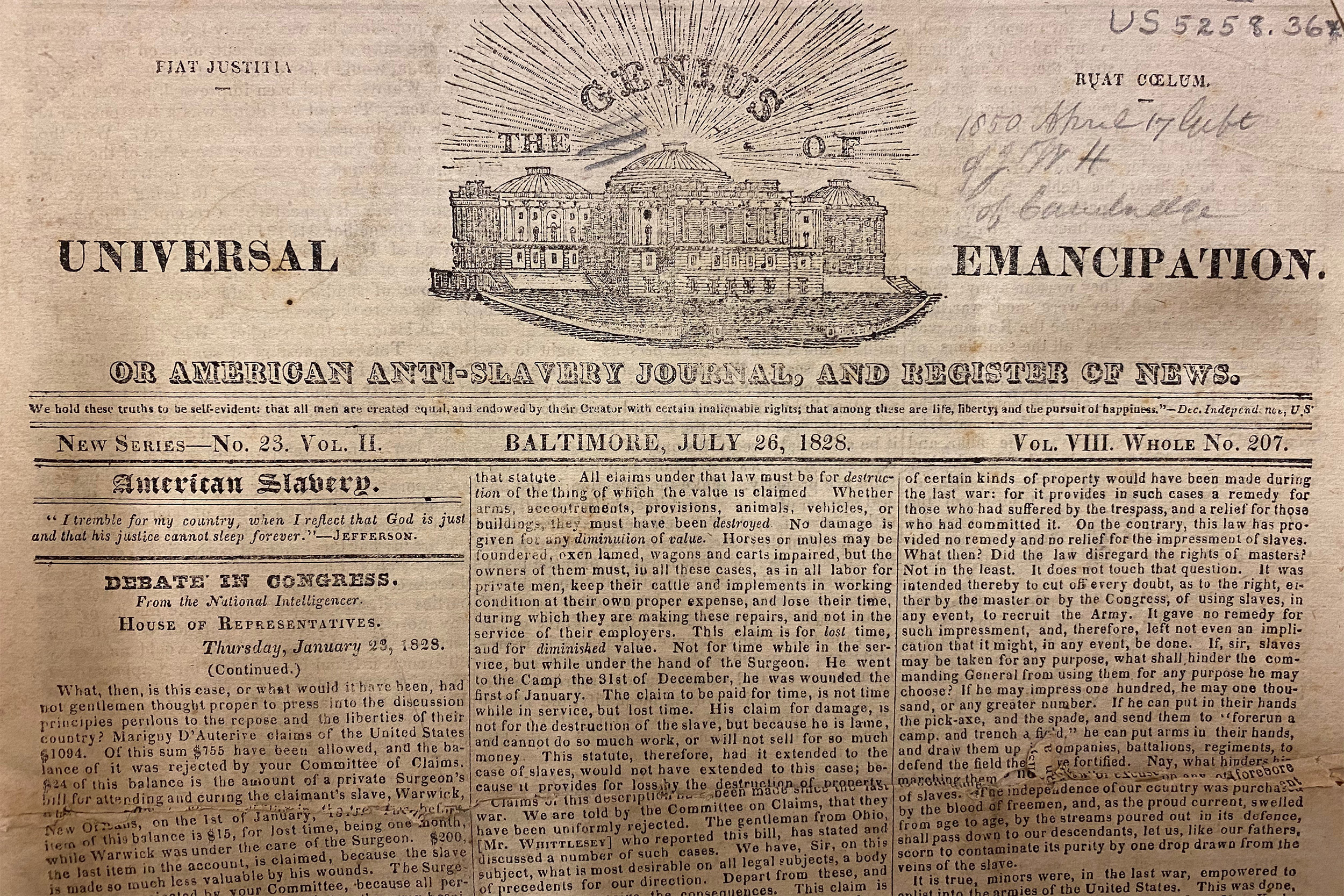

The first page from a pamphlet called “The Light and the Truth of Slavery,” which tells the story of a former slave named Aaron (circa 1845). Image of an anti-slavery newspaper taken by Dorothy Berry as she preps materials for digitization.

“We’re saying we value this work and by necessity that means pausing other things,” Berry said. “There’s a symbolism to it and also a practicality — a large-scale digitization project takes time, and we need to be able to dedicate that time.”

Berry’s background is in this work; she came to Harvard from the University of Minnesota, where she was responsible specifically for the digitization of African American materials held in its collections.

“Houghton has digitized some other really important and incredible items,” Berry said, including some centered on other marginalized groups. But materials about African Americans have not been a strength of the library’s digitization work.

Last year, Berry started to think about what African American materials she would prioritize for digitization. “The list kept growing,” she said. “At this point it’s a list of 3,400 records.”

Materials slated for digitization include written records and experiences of former slaves; abolitionist letters and meeting minutes; proceedings from racial justice-focused “Colored Conventions”; histories of Black Civil War soldiers; and bills of sale for enslaved Black people. Personal papers and photographs from individuals and families will add depth and context to the collection.

On July 27, Berry and her team began prep work, pulling items out of the collections, working with conservators to stabilize the items that needed it, and modifying or adding to many of the item descriptions. Imaging Services will do the actual scanning and digital image work.

By next summer the project will have its own collection page, including curatorial guidance for the materials, plus supplemental research and biographies of some of the collection’s key Black authors. The collection metadata will also be made available as research data to support future digital scholarship focused on Black American history.

Berry believes the future site’s users will not be limited to scholars who are already familiar with the Harvard catalog. She said many Black history researchers, including some experts, who work outside academia are often unable to access digitized primary sources related to Black and African American materials without encountering expensive database paywalls.

“A public digital collection site is one of the best ways we can assist that general user group interested in African American history,” she said.

“Digitization enables us to expand the reach of our collections,” Hyry said. “It makes [them] open and available to anyone with an internet connection.”

For Berry, the field’s ability to expand access means it can provide opportunities to promote racial equity, and she sees this year’s project as a step in that direction. By creating this large digital collection of African American materials, she said, Houghton is enabling more and different kinds of research.

“It’s just one step of many,” she said, “but Houghton is showing we’re willing to make a commitment of time and resources to prioritize this work.”