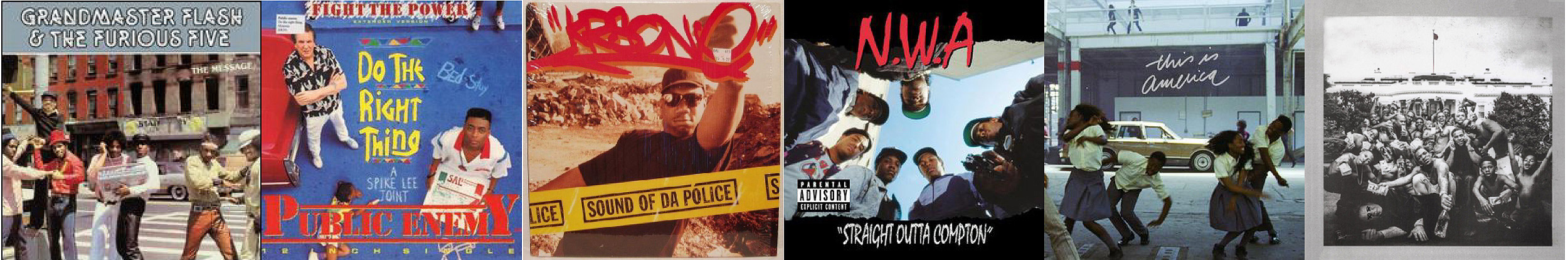

Protesting police violence, a playlist

Think of hip-hop as a historical record of the nation’s racial violence and injustice, director of the Harvard Archive says

Marcyliena Morgan is the founding executive director of the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research.

File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff

From Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five to Kendrick Lamar, long before cellphone video and social media demanded Americans witness police killings and the mundanity of racism on streets, in stores and parks, hip-hop turned a bright light on all of it, and more. Marcyliena Morgan is the Ernest E. Monrad Professor of the Social Sciences, a professor in the Department of African and African American Studies, and the founding executive director of the Hiphop Archive and Research Institute at the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research. She spoke with the Gazette about hip-hop culture’s history of exploring the systemic tangle of American racism, violence against Black people, and social, economic, and political inequality.

Q&A

Marcyliena Morgan

GAZETTE: When you think about issues of injustice and police brutality, with racism at its core, how do you think about it in terms of hip-hop?

MORGAN: We can start with Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five’s 1982 song “The Message,” which is the first prominent hip-hop song to provide a social commentary on issues affecting the Black community. It begins early with the words “broken glass everywhere,” and jumps right into a scathing critique of everyday urban life, especially in poor Black communities. Then it moves into more and more detail about racism and white supremacy in particular. Early on, one of the things that I immediately noticed about hip-hop lyrics was a social critique and exposing injustice the moment the rhymes start coming.

Scenes from Kendrick Lamar’s video for “Alright,” from 2015’s “To Pimp a Butterfly.”

When you look at the themes of racial inequality, poverty in Black communities, police violence — especially in hip-hop — you get these incredible stories about what happens when you walk out of a door in your neighborhood and even how much you love and protect your neighborhood. You work within a contradiction at the very beginning of hip-hop where, for example, “New York is horrible! I love New York!” And once it’s clear that hip-hop resists simplicity when discussing injustice, [meaning] that there’s never this moment when things will always be good or the idea that there’s going to be a consistent idyllic setting, you are ready for hip-hop. But [even then] there is still the dream of an amazing and just future. So, you get this contrast where hip-hop heads are basically saying: “Look, we are the children of the Black Panther Party. We were taught to thrive in the midst of all of this knowledge and keep moving forward. We are hip-hop.”

Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” video from 1989, directed by Spike Lee.

GAZETTE: In the late ’80s and ’90s there was a huge push in hip-hop to shed light on the experience of the Black community. A lot of it revolved around experiences with the police. Can you talk about this?

MORGAN: The police were always an object of critique. The youth of [that period] traveled to school on public transportation on the East Coast and by car and on buses on the West Coast. Interestingly enough, especially on the East Coast, critiquing social conditions and white supremacy was a major focus. In contrast on the West Coast in particular, where young people are driving, there were earlier songs directly critiquing the police. The police are stopping you — because they can. You begin to hear from a group like N.W.A., which formed in 1987. In 1988, they had their major debut with “Straight Outta Compton.” The album focused on what they considered injustices with the police. The [2015] movie on N.W.A. [also titled “Straight Outta Compton”] really was a great representation of that, too. The group starts directly addressing stories and struggles about what it means to be a young Black male, a young Black female in America in ways that represent the complexity of that.

KRS-One’s “Sound of Da Police” video from 1993.

Not surprisingly, after the album was released, more artists began talking about police abuse directly. People wrote and rhymed about how difficult it was to walk to school if you’re in a gang neighborhood. They talked about how difficult it was to get to school when the police were also trying to make sure young Black men learned that the streets belonged to law enforcement by intimidating them and depriving them of their rights. We get not just the story of “I got chased,” but songs that are much more layered like “Fight the Power” [from Public Enemy in 1989], “Sound of Da Police” [from KRS-One in 1993] a year after the beating of Rodney King. There is also “99 problems” [in 2003] with Jay-Z describing his version of an unjust traffic stop. As one listens to the lyrics in that verse you begin to realize, “Wait a minute. He’s talking about racism.”

GAZETTE: It’s impossible to not talk about N.W.A. without discussing their often-cited song “F— tha Police.” Even in the recent slate of protests, it’s been a rallying cry for some. Why is that song so poignant?

MORGAN: The song is really an amazingly creative work. It includes strong, rhythmic rhyming with content that is a story of injustice created through music samples and sounds that represent the neighborhood and its history and the people who live there.

When you listen to it, the first thing you understand is that N.W.A. is in court and you know it’s going to be a weird trial because Dr. Dre is presiding. He’s the judge. And it’s the case of N.W.A. versus the police department. You’ve got your prosecutors: M.C. Ren, Ice Cube, Eazy-E. This is a hip-hop court, after all, and it isn’t clear what a hip-hop court is at this point. N.W.A. starts making their case as the song provides specific examples of police misconduct and a legal system designed to incarcerate young people of color.

In the first verse alone, Ice Cube covers everything from Black people having it “bad” and being targeted by cops because they’re brown and directly coming out and saying because they are “not the other color” that police think “they have the authority to kill a minority.” He says he isn’t the one for someone with a badge and a gun to get beaten on and then thrown in jail or worse — and this is what we see through social media videos now, right? Then Ice Cube goes into what it’s like to be profiled as a young Black man who seems a little well off — wearing gold, having a pager. He’s getting his car searched “looking for the product” because cops think every Black person is “selling narcotics,” and, ultimately, raps/sings about how they’d rather see him locked up in jail than being a successful Black man.

N.W.A. and hip-hop, as a genre, were absolutely accurate. In 2003, I was asked to participate in a forum to educate police officers about hip-hop because in several cities it was considered a gang activity. Fans that attended hip-hop concerts became part of a national gang database. So answering the question more directly about why this song is so powerful: It begins with Ice Cube accusing America and saying: “I can see what you think about me. This is your racism. This is your bigotry. This is institutionally the way that I’m treated.” There doesn’t seem to be much about Ice Cube’s description of harassment that doesn’t hold word for word today with what many Black and brown people continue to experience.

GAZETTE: From this period, we also get another protest anthem: Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power.” On this year’s BET Awards on June 28, the show opened with an updated remix alluding to police killings and featuring artists like Nas, YG, and Rapsody, and the video is filled with current news footage of Black Lives Matter protests. What did that song tap into that makes it still resonate today?

MORGAN: It celebrated the revolutionary tradition in the Black community. “Fight the Power” channeled the ’60s, ’70s, and ’80s. It really was just a brilliant sort of bridge between the Black Power movement and what was happening in the country at that time.

It celebrates resistance. Giving up is not an option. I’m going to find songs that make me feel that I can move through this, except now, I feel like I can keep going and I know there are other people who not only are in my situation but are out there to help me. You get this sense of community and understanding and knowing what fighting the power really means. You are part of the hip-hop nation. You start to realize you can do it, and it ends with you saying we’re going to keep on going, keep fighting. The beauty of the video and message of the 2020 version is that it helps us realize that this generation hasn’t just started a movement — they’ve joined one. It’s hip-hop heads who’ve “been there, heard that and have seen that” with the next generation who will keep on keeping on. They are artists and soulmates who know what we’re fighting for.

GAZETTE: What about women in hip-hop who speak on these issues?

MORGAN: Virtually all women in hip-hop are focused on racial injustice now. That does not mean that issues of sexism, misogyny, and harassment are pushed to the side. They are in support of Black men and are founders and part of the leadership of #BlackLivesMatter. The Black community has historically favored and celebrated Black women and Black men who have also sacrificed to protect Black women from white supremacy when they could. Listen to Rapsody and Cardi B. Listen to Queen Latifah, who’s talked about how past epidemics, like HIV, have hit the Black community more than others. We should also shout out to MC Lyte, TLC, Salt-N-Pepa, and Roxanne Shante, who have rhymed powerfully about struggles with institutional poverty, health care, racism, sexism, drug addiction, and white supremacy in general.

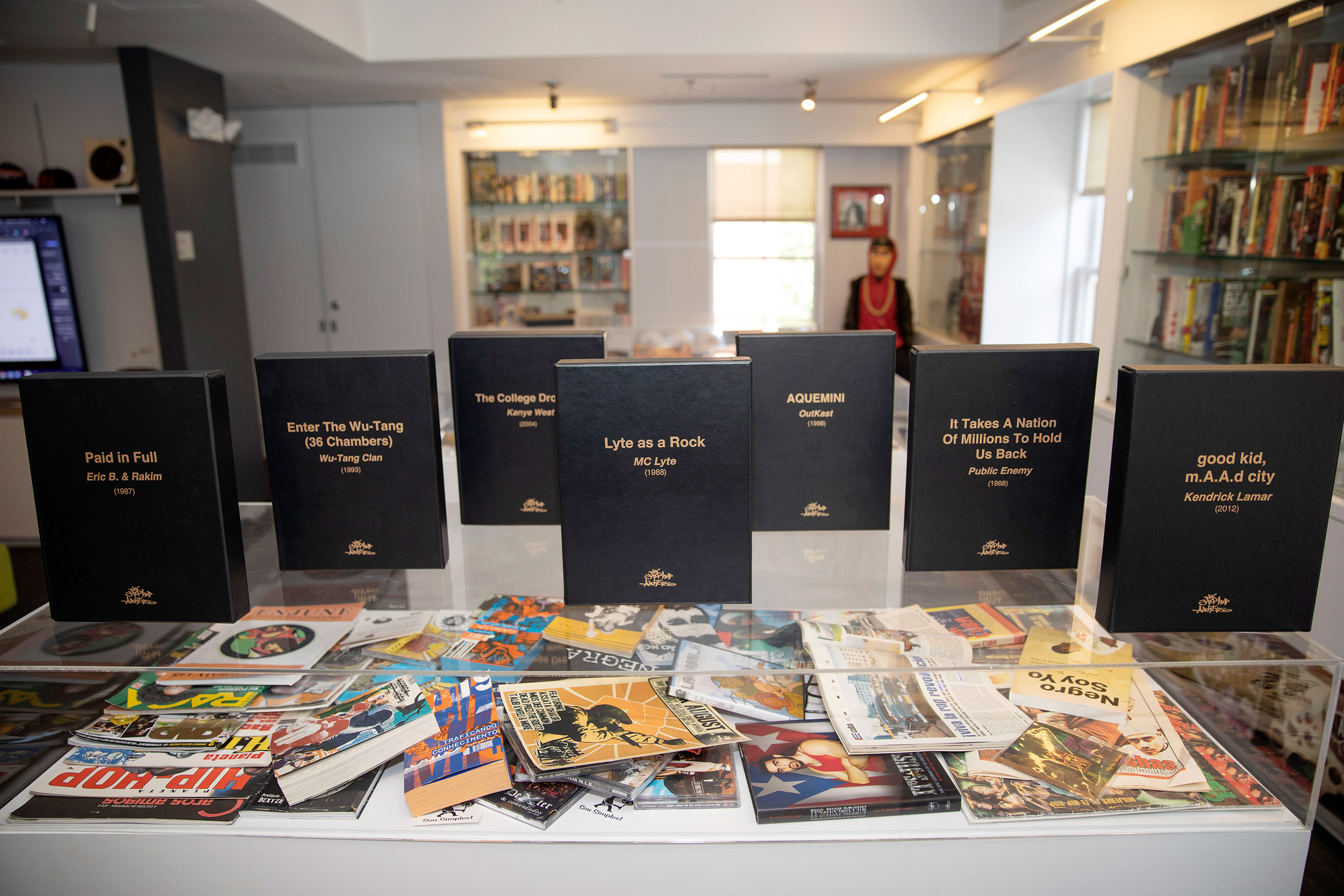

Harvard’s Hiphop Archive and Research Institute.

File photo by Kris Snibbe/Harvard Staff

GAZETTE: In more recent years, J. Cole wrote/rapped “Be Free” inspired by the death of Michael Brown. Childish Gambino had “This Is America.” And maybe the biggest in recent years is Kendrick Lamar’s “To Pimp a Butterfly.” Released in 2015, it still finds itself relevant today with themes of inequality and institutional racism. Can you talk briefly about that album?

MORGAN: The thing about “To Pimp A Butterfly” is that it manages to create a world that many of us have experienced but only really begin to understand the depth of that experience as Lamar exposes the layers of that reality. First and foremost, it is well produced. By that, I mean when you’re listening to it you’re hearing a soundtrack influenced from various periods of revolutionary struggle, so you really have in “To Pimp a Butterfly” the history of African American art, culture, and resistance. When one becomes aware of the way samples work and evolve into lyrics it becomes apparent that we are experiencing the next level of a music tradition. You’ve got jazz; you’ve got funk— spoken word, praying, rhyming.

You are forced to think about everything. What does it mean to have a soul? How do you survive? How do you come out of these situations where basically police are hunting you? They are treating you as prey, waiting for you to do the wrong thing enough times so that you end up in jail. This album, in a way, goes back to the whole notion of what it meant to do hip-hop in the late ’80s and early ’90s in terms of memories like Malcom X quotes that you can hear in Public Enemy songs. The kind of vocals you can hear in “To Pimp a Butterfly,” the argument that Kendrick Lamar is presenting — the actual content — in many ways, kept getting deeper and deeper in terms of underground explanations he gives in between songs. The album is like [a metaphysical journey from] Compton to Africa, back to Compton, and then Compton to Mars back to Compton. It was just one of these things — gifts, really — that just helped us understand that we can really go far with that dream I spoke about earlier. We can still dream. We can still imagine. It makes us think about Kendrick Lamar when he says “We gon’ be alright” — a song that became one of the themes of #BlackLivesMatter.

GAZETTE: We’ve seen artists makes statements, lead marches, release songs on these issues. Do you think hip-hop artists can do more?

MORGAN: We can always do more. Artists can always do more. But I don’t think that is what leads to sustained change. In the ’90s those who boasted that they were a part of the hip-hop nation would say goodbye with a fist bump and the word “build.” Artists and everyone must do something. Do something and be consistent. We must build. We must learn more about the past and present and the world in which we live. Listen and take responsibility for what is happening and work toward change. Always try to learn and create. Keep building.

This interview was edited for clarity and length.