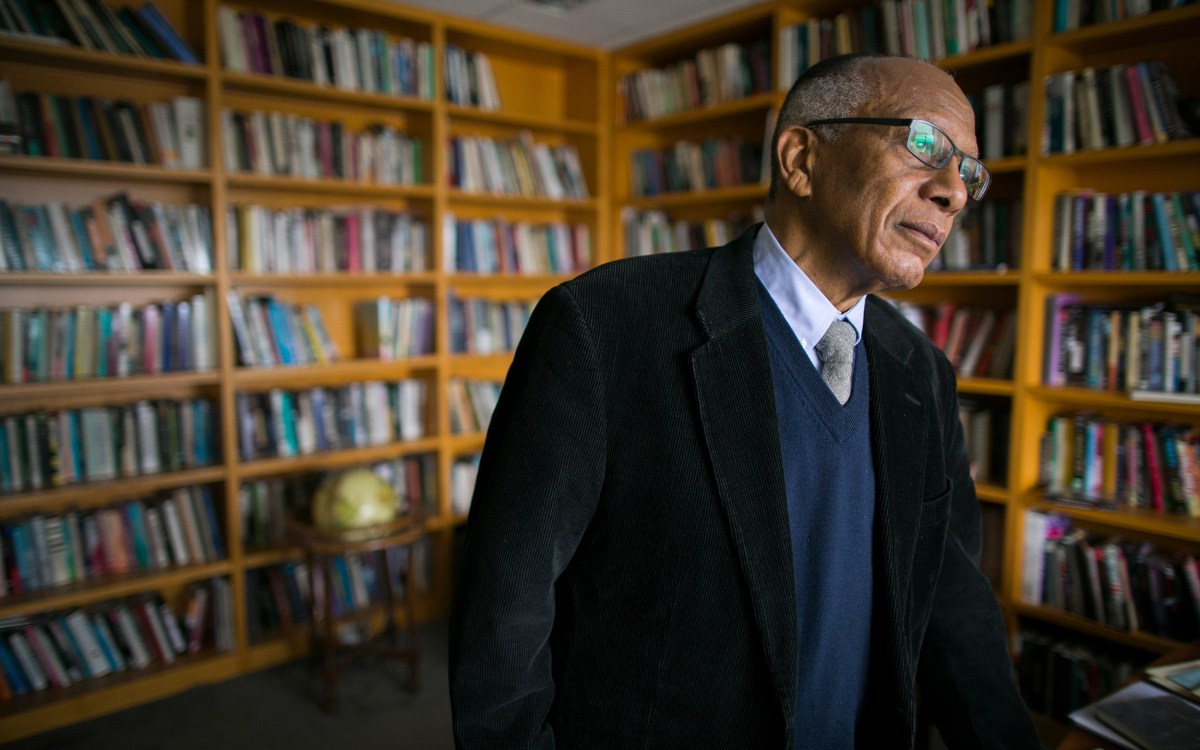

Photo courtesy of the metaLAB(at)Harvard

Fatal encounters with police

‘Their Names’ project gathers the stories of 28,000 people, from Jan. 1, 2000, to George Floyd

The oldest person on the list is a 107-year-old African American man, who in 2013, upset at being asked to move from the house where he was living, barricaded himself in a bedroom with a handgun. He fired at police when they entered the room and was killed when they returned fire.

Among the youngest is a 5-month-old African American girl who died in 2018 when the car in which she was riding fled police, crashed into a garbage truck, and burst into flames. The driver, her father, who had reportedly shoplifted from a grocery store, also died.

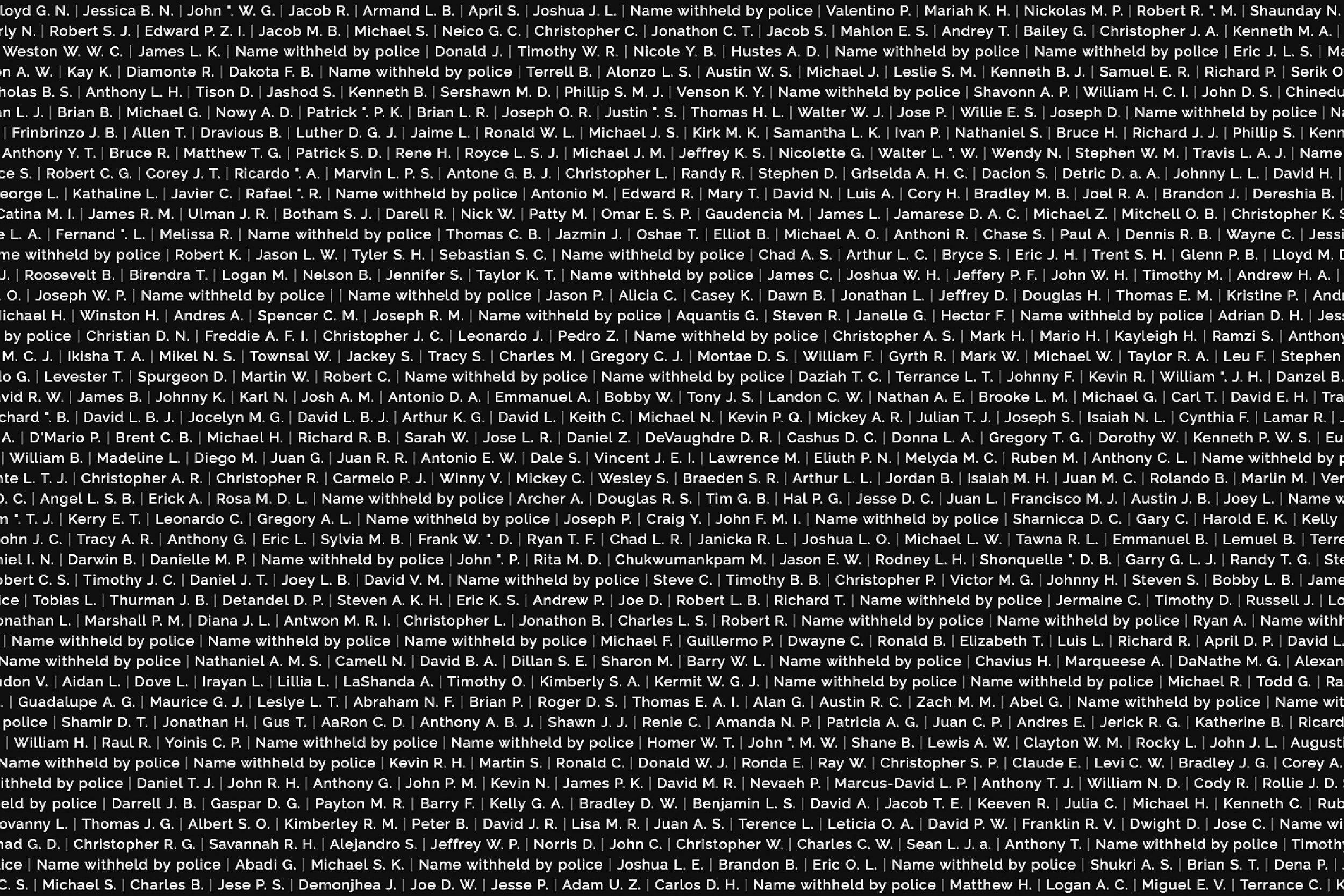

The list contains 28,000 names of those killed in police-related violence from Jan. 1, 2000, until May 25, 2020, the day George Floyd was killed during an arrest by Minneapolis police. It includes 6,000 African Americans; 9,000 white people; thousands of Latinx people, Pacific Islanders, Native and Asian Americans; and thousands more whose ethnicity is unknown. It is sortable by age, year, gender, ethnicity, location, and cause, with gunshots by far the largest number of deaths.

But numbers aren’t the point of the project, a stark-looking work of data visualization called “Their Names,” according to its creators, Kim Albrecht and Matthew Battles of metaLAB(at)Harvard. In the weeks since Floyd was killed, lots has been said about police violence, and statistics about the problem have been offered from various sources. Battles and Albrecht said “Their Names” seeks to add to the conversation by being about the people behind the numbers.

Albrecht, a data visualization designer at metaLAB, which is a project of Harvard Law School’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society, said Floyd’s death resonated because people were able to connect to his story, which illuminated a problem much larger than that single case. “Their Names” seeks to magnify that personal connection and scale it up to show the true human impact.

“The visualizations on this data all focus on analysis, on statistics, and how this problem developed over the years. We didn’t want to focus on that,” Albrecht said.

“The morbidity associated with policing in the U.S. falls disproportionately on communities of color and African American communities in particular. It emphasizes that this is not a few bad apples, but a systemic issue.”

Matthew Battles

Because there is no central repository of data on police-related deaths, Albrecht and Battles used material from a nonprofit called Fatal Encounters, which collects information about fatalities involving police as a way to fill a national information void. What set Fatal Encounters apart, Albrecht said, is that each entry links to a news article about the incident and attaches a brief summary to each name with details of how the death occurred. The dataset involves not just incidents when police seem clearly at fault, but rather surveys the broad landscape of deaths occurring when police are involved, including everything from gunshots to drownings, auto accidents to suicides. The broad view, Albrecht said, allows visitors to better understand the problem and create their own view.

Located at TheirNames.org, visitors to the site are at first struck by the stark-looking landing page, filled with small white names on a black background. Scrolling brings screen after screen of additional names. Moving the cursor over a name highlights it in red and a small summary appears. Clicking on the name brings you to the source material, like NPR’s story about the shooting of 107-year-old Monroe Isadore in Pine Bluff, Ark., bearing the headline “How Does a 107-Year-Old Die In a Police Shootout? Details Emerge.”

Battles, metaLAB’s associate director, said though the dataset details a broad array of tragic circumstances, one thing that becomes clear is the overrepresentation of minorities and African Americans.

“There are a lot of different ways that people die in this database, but the racial disparities are still the strongest signal, demographically,” Battles said. “The morbidity associated with policing in the U.S. falls disproportionately on communities of color and African American communities in particular. It emphasizes that this is not a few bad apples, but a systemic issue.”

Battles said they want the site to add to the national conversation on the problem, one they hope this time leads to real change. To encourage exchange of views, they collect visitor feedback via a questionnaire that polls attitudes toward policing in America.

“This is raw stuff to work with, and we’ve only worked with it for a couple of weeks,” Battles said. “It really makes us appreciate of the work of activists and researchers who’ve been contending with state-sanctioned violence for whole careers. The work carries a lot of trauma and it takes a lot of courage and resilience to address it.”