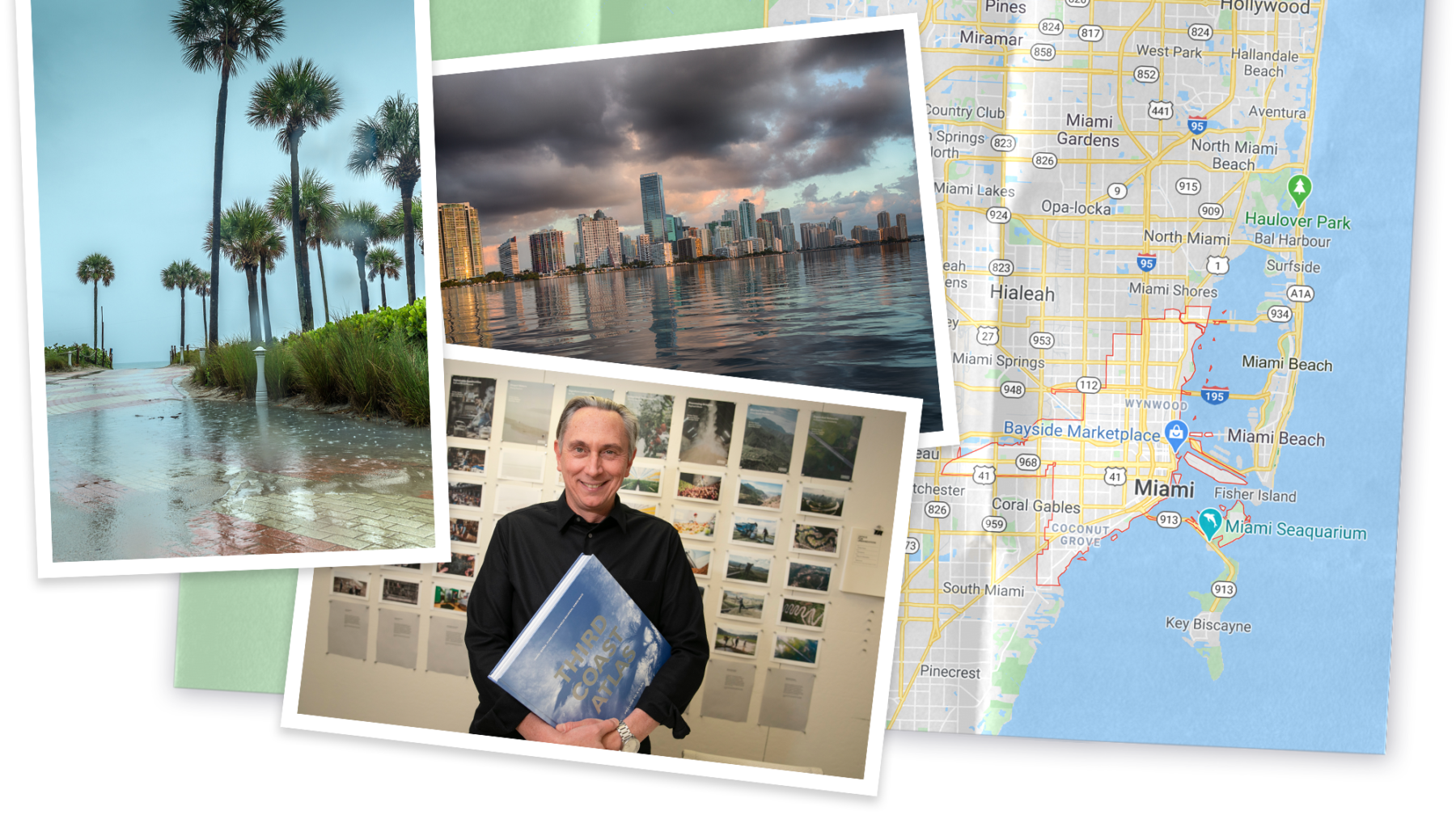

As part of the “Future of the American City” initiative, Charles Waldheim and his team have created proposals to help Miami adapt to rising seas and a changing climate.

Photos from iStock and Jon Chase/Harvard Staff Photographer

Future design

“Our right of use laws, our zoning, and our land use policies — all of those things were written for a very different war.”

Even on sunny days, flooded streets have become more common in Miami as the climate continues to warm and sea levels continue to rise. And Atlantic storms, a regular feature of South Florida life, pose a greater threat to life and property than ever before.

It’s a challenge that is expected to worsen; the coastal city projects that by 2030, sea levels will be at least 6 inches higher, and minimally another 14 inches by 2060.

Miami is betting it will be able to adapt, however, and Florida native Charles Waldheim, the director of the Office for Urbanization at Harvard Graduate School of Design, is leading a team of faculty, students, and fellows doing research to help the city do just that.

In 2018, the group began spending time in Miami as part of the first phase of the “Future of the American City” initiative, an urban study aimed at helping localities find remedies for challenges such as adapting to climate change.

Miami seemed like an ideal place to launch the initiative, given the urgency of the problem and the South Florida city’s desire to preserve its distinct, colorful character. The community has already invested $500 million into elevating roads and pumping out water, but Waldheim is convinced there are still other infrastructure improvements that can be made without marring the personality of the place.

One of the project’s proposals for Biscayne Bay showing a different approach to landforms, public paths, and vegetation.

Photos courtesy of South Florida and Sea Level Rise: The Case of Miami Beach, Harvard Graduate School of Design, Office for Urbanization, 2017

“You can pump and pipe and elevate your way out. But you can very easily end up building a city you don’t recognize,” he said. “We put in place mechanisms to enable adaptation to maintain the character, building a unique and new identity for Miami Beach without engineering ourselves into a place that makes it not so desirable.”

The team’s proposals include reimagining the Collins Canal as a stormwater reservoir, using more salt-tolerant grass in the city to help Florida’s limestone base absorb water faster, and constructing a pedestrian baywalk along the water that doubles as a storm-surge barrier.

The plans are as collaborative as they are innovative. During the semester, students spend at least a week on the ground with local leaders who give feedback on how well their proposals would work in the community, and ask for feedback themselves on policy changes.

Those strong local ties also ensure that the officials, who have a finger on the pulse of their community, have the team’s expertise available when making decisions that will have an impact for decades to come. Recently, the mayor, city council, and city manager used a report by Waldheim’s team as input prior to releasing policy revisions around climate change preparedness.

Waldheim says his team is focused on practical steps with a simple goal: less water.

“The public realm will be drier. Just at that level, there will be fewer lost days, fewer opportunity costs associated with water in the streets, impeding travel and impeding commerce.”

This story is part of the To Serve Better series, exploring connections between Harvard and neighborhoods across the United States.