Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer Alex Wu, Sc.D., M.P.H. ’18, took a photo during his nine-hour commute from the Native American community where he was deployed to his home in Portland, Ore.

Photo by Alex Wu

A COVID-19 battle with many fronts

Alumni spearhead public health campaigns, data visualization maps, and outbreak plans for Native American tribal leaders

The stories of how the COVID-19 pandemic has upended work and life are as diverse as the new challenges and pressures the disease has created. The Gazette asked alumni who are engaged in the battle against the disease to share their experiences and how their work has radically changed.

NGOZI EZIKE ’94

Chicago

Director of the Illinois State Department of Public Health

Ashlee Rezin Garcia/Chicago Sun-Times via AP

For leaders of public health departments across the country, the pandemic has meant a stark new reality of always feeling behind, difficult decisions, endless workdays.

Ezike remembers waiting for an individual’s test to come back from the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The call came late in the evening: a positive result, the second confirmed case of COVID-19 in the U.S.

“The CDC was on site the next day,” she recalled. “We were all on site at the hospital, working out the plan to identify all the people that this individual would have come in contact with for the preceding 14 days.”

Her team also had to notify the health care workers who had come in contact with the patient. “It was just a tremendous frenzy. This was brand-new. We were building the plane while we were trying to fly it.”

Some days later she got a call from the head of infectious disease at the CDC. “We were basically going to have 48 hours to plan for screening at O’Hare International,” she said. “That was another frenzied moment.”

When the next outbreak arrives, “I hope we won’t find one group bearing the higher proportion of burden of that disease.”

Ngozi Ezike ’94

When she talks about how her team has performed, the pride in her voice is clear. “Everyone has been stretched to their limits and is working so hard because they know how consequential the work they’re doing is,” she said. “When I say [the work] is 24/7, I mean it.” She reports some conference calls start at 11:30 p.m., and then others at 6 a.m. “There are no other hours available because everything else is full.”

And they have made progress. “We were the first public health lab in the country to start testing for COVID-19 onsite,” rather having to send to the CDC and wait for results, said Ezike.

Ezike said she knows the pandemic is affecting lives in a multitude of ways, “whether it’s financially or social isolation almost to the point of depression.” This brings with it what feel like impossible decisions. “We’re trying to protect everyone’s physical health, to keep them from contracting the virus, from getting sick and dying from the virus,” she said. “But at the same time, the measures put in place to promote that [like stay-at-home orders] are now taking away livelihoods.”

In fact, Ezike said her office gets calls from residents who are facing such choices. They appreciate the risks but are being squeezed: “They say, ‘I’m desperate to get back to work. I’m already months behind on my rent.’”

Ezike is looking forward to a time after the pandemic. She hopes the lessons about mitigating the spread of disease will mean it will become “unacceptable to have the tens of thousands of deaths that we have every year from influenza.”

She also hopes there will be “a focused eye on long-term care facilities, making sure that they have all the infrastructure and supports they need, so that our most vulnerable, most treasured citizens are not targets for widespread morbidity and mortality.”

She is also thinking about the existing disparities in health care, like those suffered by African Americans. When the next outbreak arrives, she said, “I hope we won’t find one group bearing the higher proportion of burden of that disease.”

RITU SADANA, Sc.D. ’01

Geneva

Senior Health Adviser, Head of the Ageing and Health Unit, World Health Organization

When Sadana watches media reports about the COVID-19 pandemic, especially about the risks older populations face, she feels a sense of urgency — and responsibility. “The speed and severity of the pandemic has touched many lives, with deaths particularly concentrated in older adults and those with underlying conditions,” she said. “You want to get accurate information out, and you see that this is exactly an area where you can make a difference.”

Besides her work with the Ageing and Health unit, Sadana also coordinated development of the WHO global strategy on aging and health, drawing on expertise from their six regional offices, many countries, and civil society organizations.

The WHO Health Emergencies Programme “is really at the heart of [the agency’s] COVID response,” Sadana said. “Infection prevention and control procedures were one of the top priorities,” she said, so her team was tasked to work with others across the agency to quickly draft a technical guide on infection prevention and control in long-term care facilities.

“I hope a year from now that we will be able to say that we did our piece and that the wave of the epidemic is under control by then.”

Ritu Sadana, Sc.D. ’01

They then brought together a group of about 20 experts in geriatrics and 100 more in infection prevention and control from around the world “to review the draft, discuss it, improve it.” Sadana said the challenge is obviously to get the science right, but it’s called an “interim guidance” for a reason: Time is critical, and updates are issued when new evidence is collected. “We really had 10 days to get the first one out,” she recalled. “I’m still amazed [that] it was possible to get it done [so quickly].” She said the dedication of professionals on the team, especially her colleague Yuka Sumi, and the willingness of experts from around the world to donate their time, attests to the convening power and role WHO plays.

Their second technical guide addresses health and social care workers in primary care who provide support for older adults.

Having accurate data is critical, said Sadana. She points to the dashboard the organization created that captures the cases and deaths based on what countries report. At the end of April there were 3 million cases and more than 200,000 deaths worldwide reported to WHO, “but not all countries are reporting cases or deaths to WHO by age and sex,” she said. Her department is part of the agency’s efforts, for example, to “advocate that deaths in care facilities or deaths outside of hospitals are also counted.” The data WHO provides is critical to understanding the impact the disease is having. Sadana noted that WHO’s European Regional Office’s weekly surveillance reports showed that 95 percent of COVID-19 deaths were in persons age 60 years and over.

“Every person has the right to health and access to treatments,” said Sadana. That value stands at the core of WHO’s mission and her work there. “It’s important to have ethical principles, but we need to have guidance that puts these in practice and doesn’t neglect older people’s needs and [that doesn’t] discriminate based on age.

“We’re trying to step up to the challenge, and I hope, I hope a year from now that we will be able to say that we did our piece and that the wave of the epidemic is under control by then.”

SANJAY SHETTY ’96, M.A. ’96, M.D. ’00

Dallas

President of the South Region for the Steward Health Care system

When the pandemic began to spread, Shetty said it felt as if he and his teams were “mobilizing for war.” Shetty has responsibility for 12 medical facilities in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Florida, and he is focused on preparing those facilities and his staff for to meet the demands of the pandemic while simultaneously managing the hospitals’ day-to-day operations.

The pandemic has put Shetty and his teams in uncharted territory. “I’ve never seen anything like it,” he said. “Our system has never seen anything like it. It’s such a fundamental disruption to everything that we usually do that, in a sense, we’ve had to throw away the playbook and start over.” At the same time, he’s been inspired by everyone he works with. Despite the potential risks, “no one is saying, ‘I’m not coming to work. I’m too scared. I can’t do this.’” And despite the other personal challenges they’re facing (such as child care while schools are closed), “everybody’s somehow making it work and then coming to work to do their jobs,” he said.

“[The pandemic] is such a fundamental disruption to everything that we usually do that, in a sense, we’ve had to throw away the playbook and start over.”

Sanja Shetty ’96, M.A. ’96, M.D. ’00

In fact, a group of nurses from the Texas and Florida hospitals he oversees stepped up to meet another community’s need, volunteering at a hospital in Southeastern Massachusetts. He said the nurses were greeted with applause. “People were so grateful to them for coming and volunteering to join the fight, you know, leaving the comfort of home, leaving families.” Shetty said when the team returns, “not only will they be coming back to care for patients, but they’ll be bringing back a ton of expertise.”

Shetty has turned to his classmates and “the network of Harvard friendships” in recent weeks, for inspiration, and also for connections and resource-sharing. “You hear from a classmate who’s working on drug development, one who’s on the front lines in an ICU in Boston, another who’s in New York City.”

Through those friends, Shetty also came across the story of a 1996 graduate of the College who wrote about his experience of being on a ventilator. “Here’s a patient who’s telling us what it’s like and how scary it can be,” Shetty said. It was a powerful, human story, and a reminder of the responsibilities medical professionals have, he said.

YIJIA CHEN, M.L.A. ’17

Boston

Landscape Architect with DumontJanks

YUJIA WANG, M.L.A. ’17

Lincoln, Neb.

Assistant Professor of the Practice at University of Nebraska-Lincoln; Principal at Yichang Landscape and Planning

For designers Chen and Wang knowledge is power, especially during a pandemic when misinformation is “flying around,” and the public needs information that is accessible and current. Collaborating remotely, Chen and Wang created their Datamap Project, an online “spatial data visualization” of the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S.

When the outbreak began in China, Wang, who has family and friends there, found he was turning to whatever data, graphs, and maps he could find. As parts of China issued measures to slow and contain the spread of the virus, “you can imagine the level of stress” for people, he said.

Information became “a calming factor,” helping people understand “what they were dealing with in the immediate areas where they live.”

Yujia Wang, Co-creator of the Datamap Project

While most of his friends and family were in cities “not hit particularly hard,” he found himself pointing them to the maps even so. Information became “a calming factor,” helping people understand “what they were dealing with in the immediate areas where they live.” Watching the number of cases in the nation decrease provided hope, because, as Wang put it, people could “clearly see the light at the end of the tunnel, both on a national and local level.”

More like this

He and Chen then set out on their Datamap Project with the goal “to inform the public of what is going on around them through this spatial data visualization.” They wanted “to promote accessibility of information to aid decision-making, and to encourage an evidence-based, objective approach toward this outbreak.” Being able to visualize the disease’s spread, they hoped, would convey the seriousness of the message to “stay at home and help flatten the curve” as well as provide some small measure of comfort.

Putting the spread of the disease in geo-spatial terms “is probably the most relevant and easy-to-understand way to contextualize the numbers,” Wang believes. “Numbers don’t have meaning and context until you put them in space.”

No maps they had seen were mapping county-level data, so they wanted to include that as well as hospital information, “including number of beds available in total, hospital location, and a ‘load factor’ to show [if a hospital was] getting anywhere close to capacity.” Wang pointed to where color on the map was darkest. That indicates locations where “the bed/patient ratio is showing a 0, 1, or 2.” He explained, “This means that the medical resources are probably stretched thin.” Wang and Chen hope this information, for example, could be used by those wanting to support hospitals most in need.

Wang and Chen felt it was essential the map be an open-source project. “We felt like that was an important component of transparency,” said Wang, who said he hopes that others who want to can learn from the algorithm they used for the visualization.

The duo noted that their education from the Graduate School of Design was influential, with its many “system thinkers” engaged in the “conversation on urbanism, resiliency, conservation, revitalization, and social justice,” said Wang. “That’s how we ended up working together on this.”

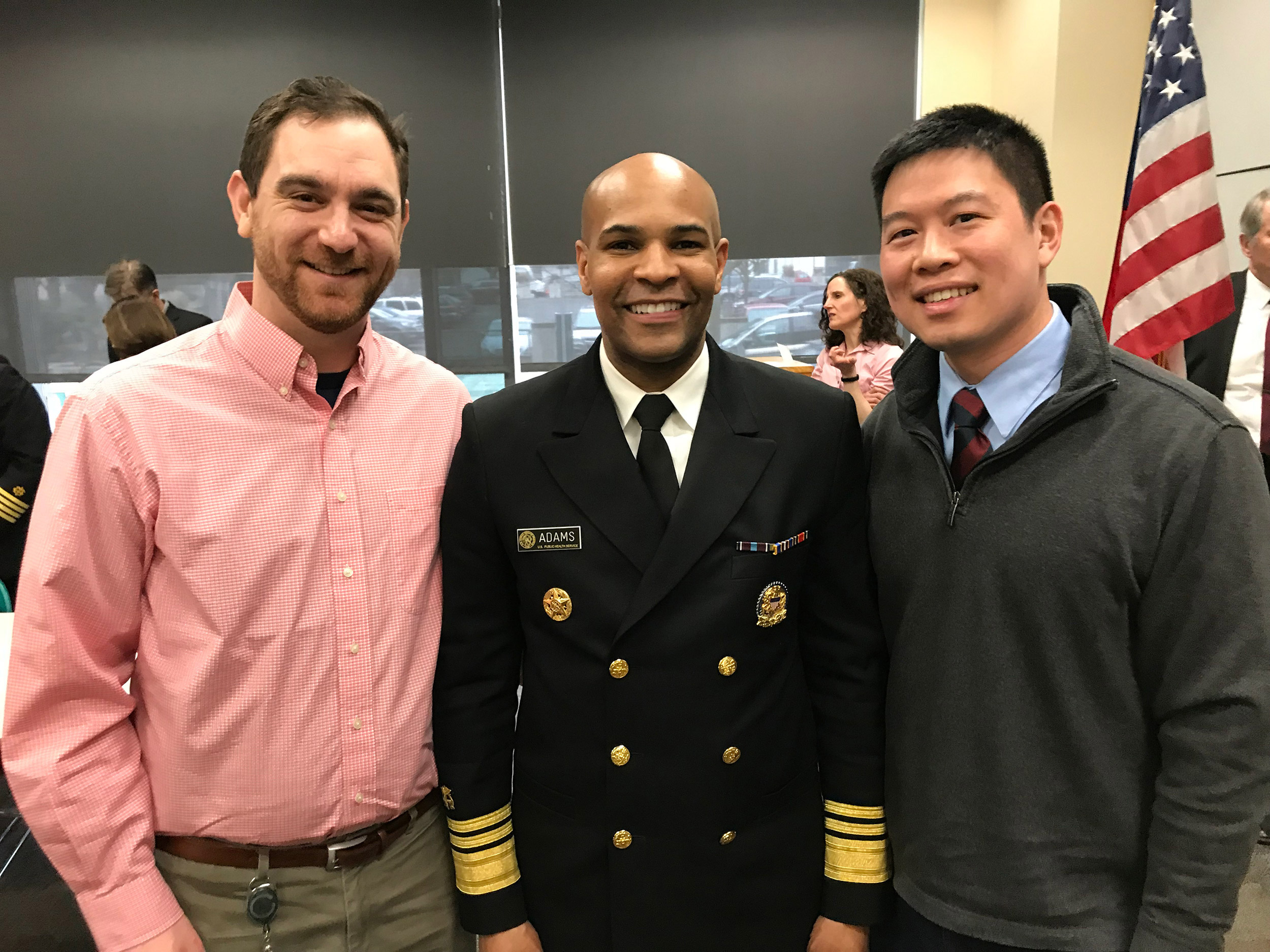

ALEX WU, Sc.D., M.P.H. ’18

Pacific Northwest

Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) Officer, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Alex Wu (from right) with U.S. Surgeon General Jerome M. Adams and Epidemic Intelligence Service Officer Steven Rekant.

Courtesy of Alex Wu

Wu, a second-year EIS officer, recently returned from an unusual solo deployment in the Pacific Northwest, where he worked with a Native American community. “EIS officers are rarely sent into the field alone, but because there are so many places that need our help right now, I found myself deployed as a one-person team,” he said.

After nine hours of travel from his home in Portland, Ore., he arrived at a reservation and immediately got to work, meeting with the tribal council. The leaders told him the tribe was worried about what would happen if the reservation experienced a surge in COVID-19 cases, Wu said. They had questions about how best to support community members who may be isolated or even quarantined and how to protect their public health workers. They also asked for guidance on how to report case and contact information, specifically what kind of organizational structure would be needed and how the tribe’s Emergency Operations Center should be involved. Of course, Wu said, “They also asked the same question a lot of people have right now: When will life get back to normal?”

Wu listened to the tribal leaders discuss the practical approaches they had developed for dealing with COVID-19. Then he explained “how [those] practices could align with CDC guidelines to protect their tribe.” Wu also provided training to community members who would serve as contact tracers. Working alongside tribe members, he was able to “develop an organizational chart showing what each group on their response team would do if there was a surge.”

At night, Wu — who also assists the executive director of the Northwest Portland Area Indian Health Board, answering questions about COVID-19 on weekly video conference calls with over 200 tribal clinicians nationwide — returned to his nearby motel room to review what he’d heard and “to think about what else the tribe needed.” Wu said his supervisor would call to check in every evening. Being a “one-person team” made the communication especially welcome, he said. In addition to the guidance his supervisor would provide, “it was immensely helpful, mentally to have these evening discussions.”

A few days after Wu returned home from his recent deployment, he got a call from the tribe’s leaders: The surge they had feared had arrived. “They were prepared,” he said. “Their trained team of contact tracers knew what to do and how to report the information they collected. Their workers who had to make house visits knew what to do to protect themselves.” Wu said the call made him grateful for the experience.