Stephanie Mitchell/Harvard Staff Photographer

Tracking the coronavirus through crowdsourcing

How We Feel app uses big data analysis to help fill information gaps created by a testing shortage

Efforts to get a handle on the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. have been hampered by the lack of widespread testing. Most public health experts, in fact, say that absent the emergence of a treatment, vaccine, or herd immunity, having data from a robust national program should be a precondition to reopening the nation.

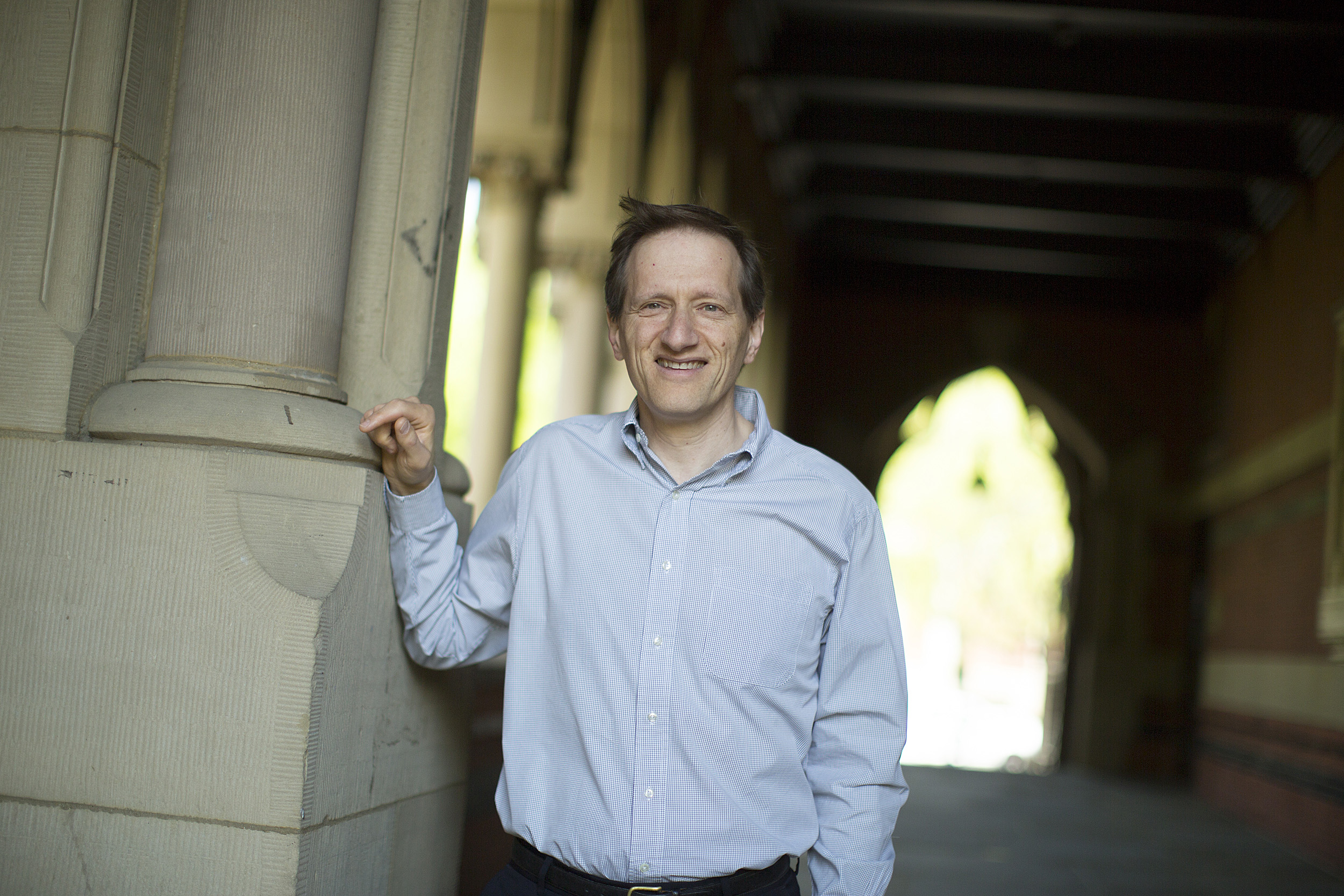

Trying to begin the task of gathering data on the spread of the disease is the goal of a new crowdsourcing app, How We Feel, which launched this month in a collaboration involving Pinterest CEO Ben Silbermann and researchers from Harvard and other institutions, including Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute and MIT, Xihong Lin, professor of biostatistics at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and a professor of statistics at the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Gary King, director of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science (IQSS) at Harvard.

The idea for the nonprofit came from Silbermann and Zhang, best known for pioneering the CRISPR gene-editing technology. The two longtime friends met in high school in Iowa, and after the outbreak began they started talking about whether their expertise in technology and biology, respectively, could be leveraged to find a way to make up for the lack of reliable testing data.

“Since high school, my friend Feng Zhang and I have been talking about the enormous value of connecting citizens to the global health and research community,” Silbermann said in a statement. “When we saw how quickly COVID-19 was spreading, it felt like a critical moment to finally build that bridge between citizens and scientists that we’ve always wanted. How We Feel is an important first step.”

“If we get even one more person to help then everybody will benefit.”

Xihong Lin, professor of biostatistics

This is how it works. Users can download the free app for Android or iOS. They are then asked to anonymously enter their ZIP code, sex, age, race and other demographic information, health conditions, pertinent lifestyle data (such as whether they smoke), any coronavirus test results, and, most importantly, how they are feeling on a daily basis. If participants report they aren’t feeling well, it prompts more specific questions about symptoms.

Researchers then analyze that data using novel statistical methods developed at Harvard to pinpoint hotspots and predict the percentage of people who have the disease in different regions of the U.S. The information could shed light on key blind spots if enough people sign up and use it daily.

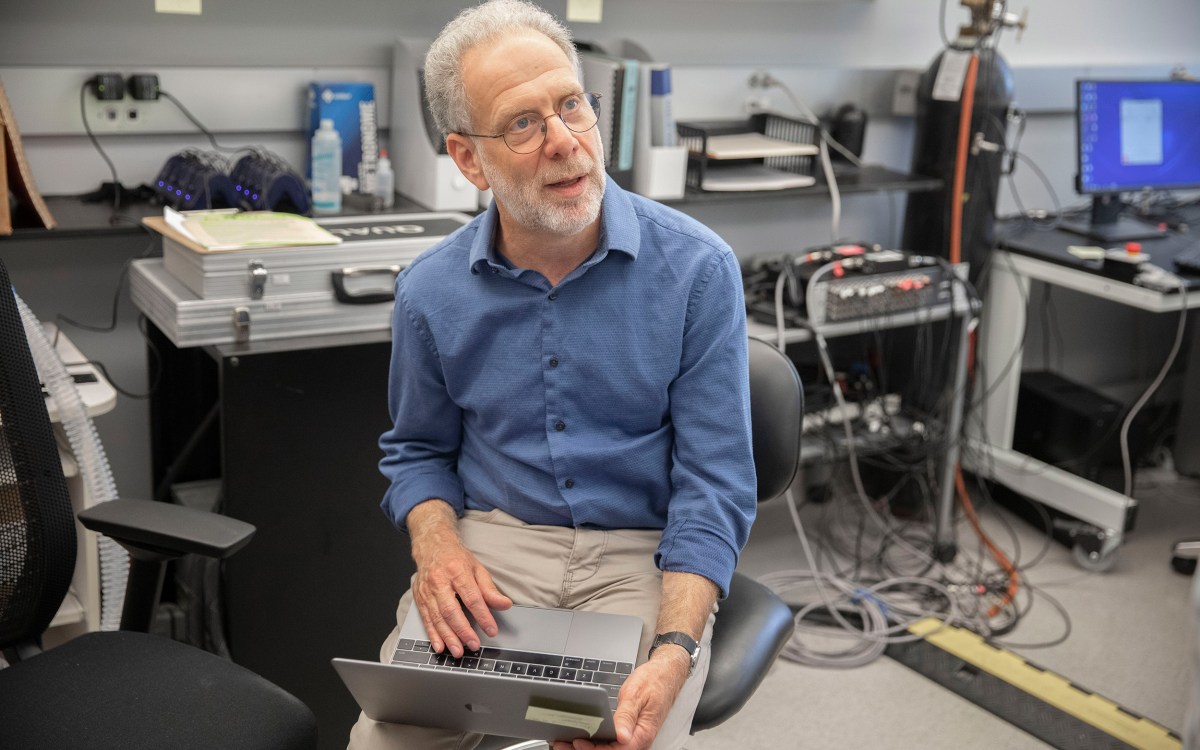

“Although symptoms alone cannot diagnose the disease in any one person, our statistical methods make it possible to accurately estimate the prevalence of the disease in different populations, locations, and other subgroups,” said King, who is also the Albert J. Weatherhead III University Professor.

Gary King, director of the Institute for Quantitative Social Science (IQSS), is on the research team to help develop the app.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard file photo

The data can give health officials a more complete understanding of the outbreak so they can bring extra attention to critical areas.

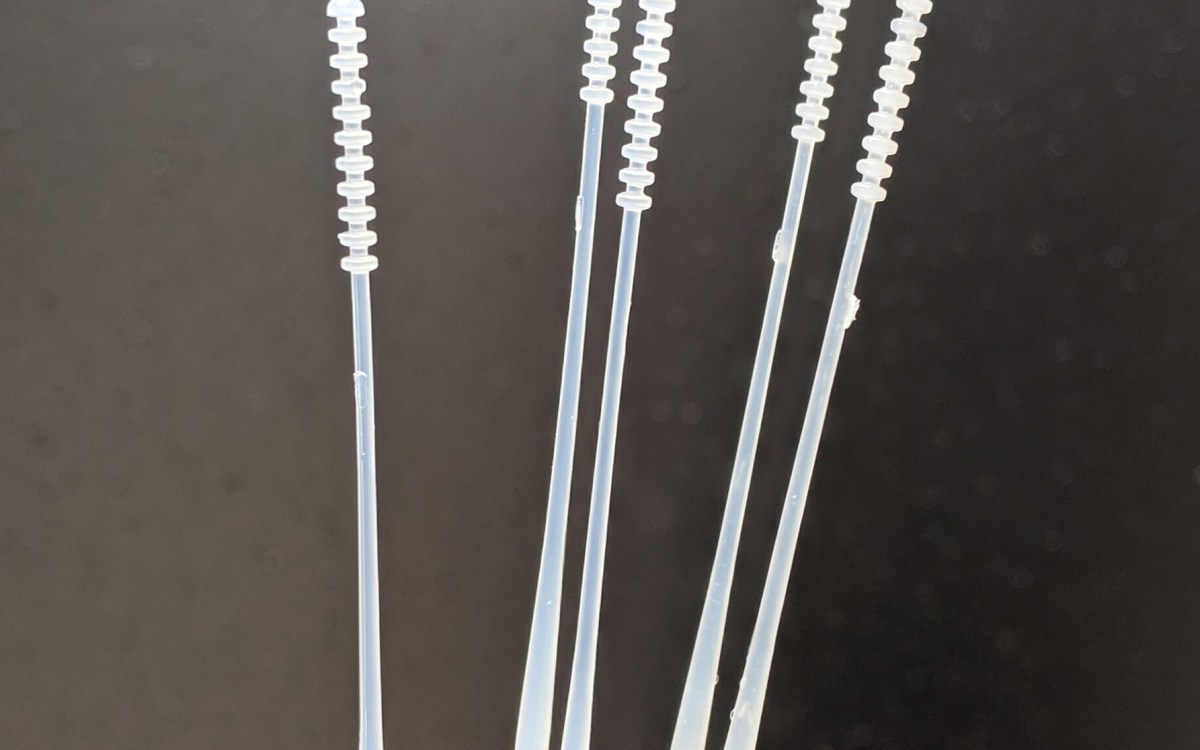

“This will help us think about how to allocate testing resources,” said Lin. “Right now, there is a serious shortage of [testing and testing supplies such as] swabs, so this could help us estimate how much the need is and then we can prioritize.”

As an added incentive, Silbermann and his wife, Divya Silbermann, will donate a meal to the food bank operator Feeding America each time someone new registers. They have pledged up to 10 million meals.

More than 450,000 people across the U.S. have already used the app, providing over a million responses. Connecticut became the first state to encourage statewide use on April 20. The aim is to get as much of the U.S. population on the app as possible.

“When we saw how quickly COVID-19 was spreading, it felt like a critical moment to finally build that bridge between citizens and scientists that we’ve always wanted.”

Ben Silbermann, Pinterest CEO

The app’s daily health checks take about a minute. Users can share whether any family members or close contacts have symptoms or are infected. They can also see how other people around them are feeling based on their own location data. Users can stop participating at any point without materially affecting final results.

Researchers analyze responses to the survey questions from people who have tested positive for COVID-19 to find the statistical patterns that can help them predict aggregate percentages. Those patterns are then applied to the data from people who have only provided their symptoms, demographic, and geographical information to estimate what percentage of them have the disease. The statistical method basically involves working backward to fill the gaps on an aggregate level that mass testing could shore up using an individual approach. It does not replace testing.

King and his team developed the method about a decade ago. It’s used by the World Health Organization to estimate the prevalence of diseases and the number of people who die of them in countries where the cause of death isn’t widely recorded.

The app also uses statistical and machine learning methods developed by Lin and her team in the Chan School’s Department of Biostatistics and FAS’s Department of Statistics.

More like this

The app is the first product from the How We Feel Project, a nonprofit made up of researchers and scientists from the IQSS, the Chan School, MIT, the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cornell, Stanford, University of Pennsylvania, University of Maryland School of Medicine, and a volunteer team of current and former Pinterest employees. Its mission is to connect the world’s health community. Other collaborators include the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

The group is bringing together an international consortium of researchers who have developed similar health status surveys called the Coronavirus Census Collective.

“If we get even one more person to help then everybody will benefit,” said Lin. “It’s really critical that we as a community are united and work together and contribute every little bit, so we can fight COVID-19 together.”