Jonnica Hill/Unsplash

COVID-19 targets communities of color

Harvard experts say pandemic exacerbates longstanding inequities in American society

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

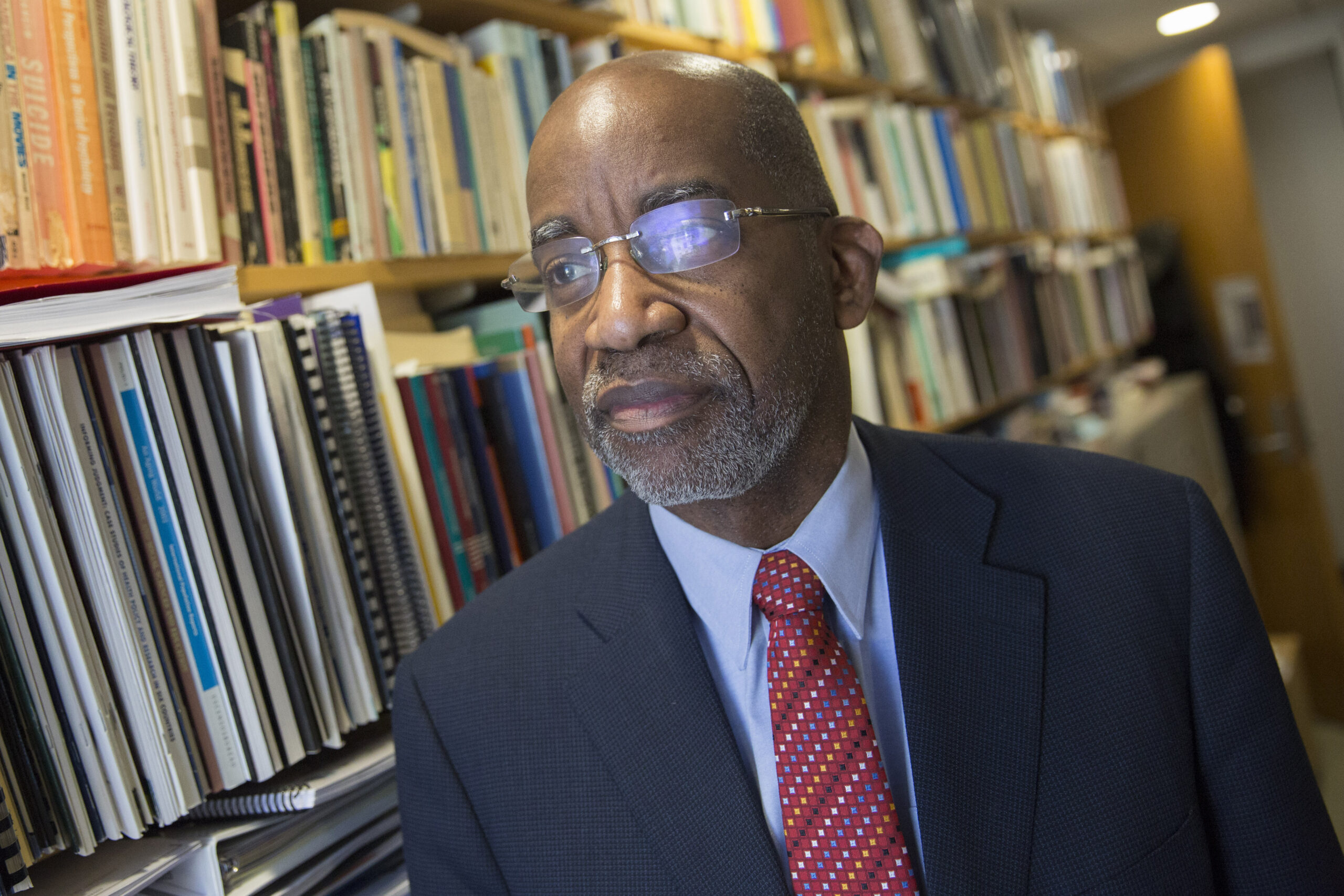

Past work by a range of scholars has shown that “200 black people die every single day in these United States who would not have died if the health experience of African Americans was equivalent to that of whites,” said Harvard social scientist David Williams during an online discussion about race and health care last week.

And the coronavirus pandemic provides new figures to support that grim statistic.

A recent CDC report found that among “580 hospitalized COVID-19 patients with race/ethnicity data, approximately 45 percent were white, 33 percent were black, and 8 percent were Hispanic, suggesting that black populations might be disproportionately affected by COVID-19.” And a Washington Post analysis revealed that in places such as Chicago and Louisiana, African Americans account for 67 and 70 percent of COVID-19-related deaths respectively, while representing only 32 percent of the population. Experts expect to see more numbers like these as more states and cities report.

“As someone who has studied the devastating and fragmented HIV epidemic in African American communities, I had become increasingly concerned that something similar might be happening with the spread of the coronavirus, in other words, that communities of African American people are at risk,” said Evelynn Hammonds, Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, last Thursday during the debut of the webinar series “Epidemics and the Effects on the African American Community from 1792 to the Present” by the Project on Race & Gender in Science & Medicine at the Hutchins Center for African & African American Research.

The recent headlines, added Hammonds, who is also a professor of African and African American Studies, “began to highlight my worst fears.”

While Thursday’s talk helped shine a light on the health disparities related to coronavirus, across the University health care disparities more broadly have long been a focus of academic investigation and research. Those who have spent years studying the issue say the higher rates of conditions such as obesity, diabetes, asthma, and heart disease in African American communities — conditions that put people at higher risk of death from infections with the novel coronavirus — is a societal failure.

“It’s been hard for Americans to understand that there are racial structural disparities in this country, that racism exists,” said Camara Phyllis Jones, an epidemiologist, family physician, and senior fellow at the Morehouse School of Medicine. “If you asked most white people in this country today, they would be in denial that racism exists and continues to have profound impacts on opportunities and exposures, resources and risks. But COVID-19 and the statistics about black excess deaths are pulling away that deniability.”

Jones, whose work examines the impacts of racism on the health and well-being of the nation, and who is the 2019‒2020 Evelyn Green Davis Fellow at the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study, points to residential segregation as a driver of broad health disparities.

“It’s segregation in terms of access to healthy foods, and to green space, and excess exposure to environmental hazards, which is why we have things like more obesity leading to more diabetes and more heart disease and more kidney failure,” said Jones.

Similarly, those and other social and economic inequities also have led to the higher rates of African Americans contracting the coronavirus, a range of experts say, as opposed to any genetic or biological predisposition.

“The coronavirus is really exposing class- and race-based vulnerabilities, particularly in the form of what I think of as toxic inequality, especially the clustering of COVID-19 cases by community,” said Robert Sampson, Henry Ford II Professor of the Social Sciences.

“African Americans, even if they’re at the same level of income or poverty as white Americans or Latino Americans, are much more likely to live in neighborhoods that have concentrated poverty, polluted environments, lead exposure, higher rates of incarceration, higher rates of violence — so that goes beyond individual poverty … and we know that many of these things lead to long-term health consequences,” he said.

Sampson, who studies links between poverty and social mobility, is one of many scholars at Harvard targeting inequality. In 2016, he published a paper demonstrating that Chicago’s black and, to a lesser extent, Hispanic neighborhoods disproportionately bear the burden of lead toxicity that is often found in the city’s soil, old paint, and plumbing. He describes the findings as “the ecology of toxic inequality.”

Adding to the risk amid the current pandemic, said Williams, the Florence Sprague Norman and Laura Smart Norman Professor of Public Health, is the fact that many African Americans work in service jobs that can’t be done from home, placing them directly in harm’s way. He also cited the implicit bias in the nation’s health care system — studies have shown African American patients receive poorer-quality health care than whites — “as another dimension at which racism could also be affecting the death rates for African Americans.”

Both Jones and Sampson advocated for a more widespread national testing strategy for the coronavirus to slow the infection rate. Jones urges a turn away from a clinical health care approach that narrowly focuses on confirming a COVID-19 diagnosis for those who are sick to a broader public health, population-based strategy that tests not only those with symptoms, but also a sample of those who are asymptomatic. Such a step, she argues, could alter the course of the epidemic.

“Having that good sense of the extent of the disease will help you know where you have to deploy the health care resources in the weeks and months ahead, as well as isolate asymptomatic spreaders and their contacts,” Jones said. “And decreasing the spread of COVID-19 will be good for everybody, but especially those who are more exposed, less protected, with higher chronic disease burdens and fewer health care resources.”

To help drive change forward, Williams urges scholars to engage with policymakers. “I hope those of us in academia can work with those in policy circles to try to gain momentum, to say, ‘We have a problem as a nation; we can do better; we must do better,’” said Williams.

Hammonds also sees the need for academic engagement.

“There’s a lot of information available to people who are well-educated, who can understand the sort of analytical framework in which we come to these questions,” said Hammonds. “But it’s not well understood at the level of the high school curriculum, or the undergraduate curriculum, or even graduate school curriculum outside of professional schools of public health. So it seems to me that there’s a lot of information that is siloed that needs to be much more expanded.”

In a sign of possible movement in that direction, Vice President Mike Pence and Surgeon General Jerome Adams held a conference call last Friday with hundreds of leaders of the African America community to discuss the alarming statistics. The government is working on increased testing and outreach efforts to communities of color, Adams said after the call, and on increased social and financial supports.