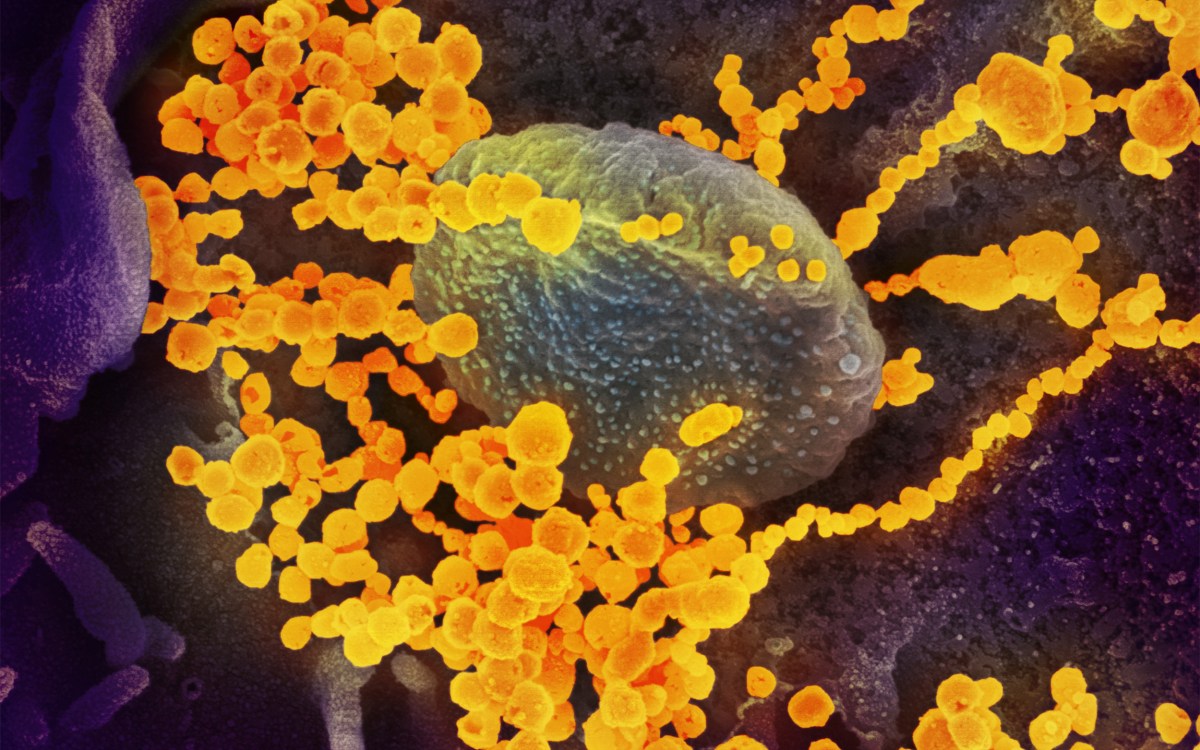

Pixabay

Epidemiologist says COVID-19 may be more infectious than thought

Citing spread on ships and health care facilities, professor suggests moving some nursing home residents out and increasing surveillance

This is part of our Coronavirus Update series in which Harvard specialists in epidemiology, infectious disease, economics, politics, and other disciplines offer insights into what the latest developments in the COVID-19 outbreak may bring.

A Harvard epidemiologist is warning that nursing homes, through no fault of their own, may no longer be the best place to house vulnerable elderly patients.

Michael Mina, an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and its Center for Communicable Disease Dynamics, said Friday that he believes the coronavirus that causes COVID-19 is more transmissible than previously thought. It has been difficult to keep it from spreading in a number of settings, including hospitals, cruise ships, and nursing homes — in Massachusetts alone, some 102 nursing homes had reported 551 cases by Sunday afternoon, according to the Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Even with current restrictions on visitors, he said, employees regularly moving in and out of the facilities means it’s likely that additional cases will occur.

“I do think as many people as we can get out of these homes, [it] is probably better,” said Mina, also a Chan School associate professor of immunology and infectious diseases and associate medical director in clinical microbiology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital’s Pathology Department. “I think that this is an extraordinarily transmissible virus. I think it’s more transmissible than we recognize and actually preventing it from spreading within nursing homes is an extraordinary feat.”

The focus on nursing homes has heightened recently, in part due to revelations of 21 deaths at the Holyoke Soldiers Home since late March, of which at least 15 were due to the coronavirus. Test results in other cases are pending. A cluster of deaths at a nursing home in Washington that began in February highlighted senior citizens’ vulnerability to developing severe illness from the virus and, since early March, nursing homes across the country have restricted visitors in an effort to reduce risk to residents. In response to the growing threat, Harvard-affiliated Hebrew SeniorLife (HSL) on Friday instituted a self-shelter-at-home directive for 1,700 residents at five senior living campuses across Greater Boston. The organization has seen 36 COVID-19 cases and nine deaths among residents, as well as eight cases among employees.

“COVID-19 is already taking a heavy toll in Massachusetts, and despite vigilant efforts that started in late February to prevent the occurrence of the virus on our campuses, it has been felt deeply,” HSL President and CEO Lou Woolf said in a statement. “Time is of the essence to self-shelter at home to protect our residents and staff from this threat.”

On Friday, the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court moved to ease crowding in another institutional setting, saying the state should begin hearings on whether to release nonviolent pretrial detainees as a way to lower risks from COVID-19 in the prison system.

The steps come as COVID-19 cases topped 1.1 million globally, with deaths exceeding 62,000, according to figures from the World Health Organization.

Mina said he recognized that some nursing home residents don’t have acceptable alternative living arrangements. Absent relocation, he advocated giving the facilities resources for stepped-up surveillance, such as testing employees every few days to keep the virus from entering and nipping in the bud any outbreaks that do occur.

“I think [COVID-19 is] more transmissible than we recognize and actually preventing it from spreading within nursing homes is an extraordinary feat.”

Michael Mina

“It’s a real concern and I think as much as we could potentially do to get people out of them would be optimal,” Mina said.

Mina, who spoke to the media in a conference call Friday, said additional testing is needed not only at nursing homes but everywhere, despite the recent rapid increase in the number of coronavirus tests conducted nationwide. In addition to more testing for virus infections, scientists also need serological tests to show how many people have been previously infected and recovered. Such tests would inform both researchers seeking to understand the pandemic and government leaders as they consider easing social distancing steps taken to reduce the epidemic’s peak. Without serological tests, months of frenzied attention on the virus will still leave us short of understanding what we’re dealing with, Mina said.

A virus that has already spread widely in the population requires a different response than one whose spread involves the cases already found through current testing, Mina said. If the virus has already infected many more people than testing to date has shown, that would mean that the very serious cases in hospitals today are a small portion of the total number, and that pouring resources into contact tracing might not be the best policy. If millions of people have already been infected and recovered, that would mean that the population is on the path to herd immunity — the threshold at which the level of immunity in a population naturally inhibits further transmission.

On the other hand, he said, if the current testing has captured somewhere close to the true number of cases, that would mean the virus is more virulent, with a significant proportion of cases becoming serious. It also means that efforts to suppress the virus through contact tracing are important.

“We still don’t know if this virus has infected say, 300,000 Americans or 15 million Americans,” Mina said. “And, until we really understand that difference, it’s very, very difficult to know how many people we need to be testing.”

Mina cited a recent study in Iceland that tested people for active coronavirus infection and found 0.5 percent to 1 percent positive for the virus. He cautioned that the study was not a random sample — people volunteered to be tested — but said if that level of the population had active virus on the day on which they were tested, then it’s likely that past exposure is significantly higher. And if those results tracked to the U.S., that would mean millions of undiscovered cases.

Mina said recognition of the need for serological testing problem is widespread in the scientific community and a variety of companies are at work on them. The tests will likely take different forms, from those that must be administered in a doctor’s office to something like modern pregnancy tests that could be sold in packs at the local pharmacy and used at home.

“We have to get to an order-of-magnitude-understanding of how many people have actually been infected,” Mina said. “We really don’t know if we’ve been 10 times off or 100 times off in terms of the cases. Personally, I lean more toward the 50 to 100 times off, and that we’ve actually had much wider spread of this virus than testing … numbers are giving us at the moment.”